Interview by Berlin Art Link // Dec. 17, 2019

Irma Blank’s work reflects on the meaning of words and the limitations of verbalisation. In her oeuvre she has created a new universal language, one that is not constrained by meaning, but which is nonetheless a form of expression. Her approach to writing is nothing short of philosophical.

The current exhibition of her work at MAMCO in Geneva spans across five decades of mark-making; it spans her life-long research into freeing writing from words. In 2016, she suffered a health problem that immobilised the right side of her body, and so she learnt to draw with her left hand. The result is the series ‘Gehen, Second Life.’ Her art and life are intrinsically linked. During her career, she was intermittently associated with the avant-garde and contemporary art scene but, even when she wasn’t, she maintained a relentless production of work, which has added to the growing feeling of respect for her among a new generation of artists and curators.

We discussed Blank’s work with the curators of MAMCO’s ‘Irma Blank’ exhibition, Johana Carrier and Joana P. R. Neves, and why she deserves the recognition she hasn’t yet received.

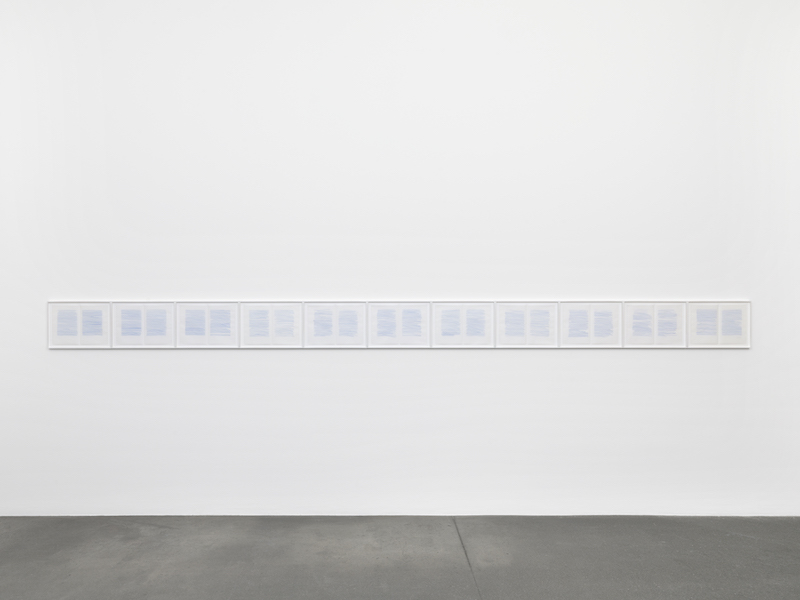

Irma Blank: ‘Eigenschriften’, 1968-73, installation view at MAMCO Geneva // Courtesy of the artist and P420, Bologna, Photo by Annik Wetter

Berlin Art Link: What inspired Blank to begin working with script and why has she continued with this practise through the last five decades?

Johana Carrier and Joana P. R. Neves: Irma Blank’s work is based on an uprooting experience: born in Germany (Celle, 1934), she moved to Sicily when she met her Italian husband in 1955. She told us that living in a foreign country and acquiring another language and another culture, made her realize that “there is no such thing as the right word,” even in one’s mother tongue. She was and still is a great reader and, to some extent, she also writes about art. Therefore, this amplification of the experience of language led to a reflection about meaning and words. This realization was the foundation of her work and it triggered her first abstract series, ‘Eigenschriften’ (1968–1973), which could be translated as “self-writings” or “writings for oneself.” Resembling undone writings, these drawings were an intimate exploration of the act of writing without words, thus freeing them from the ambiguity and the constraints of meaning. We have a feeling that they were simultaneously liberating and representative of her uprooting experience.

Then, there was a shift in this introspective experience of asemantic writing to the manifestation of the world as printed matter. She was no longer turned towards herself but towards the way the world was shaped by meaning and the use of words. Specifically, in 1973, she moved to Milan (where she still lives and works) and started doing the ‘Trascrizioni’ series (1973–1979), that takes up different typologies of printed text, from novels to poetry and newspapers. She thus copied and translated to her specific kind of writing without words, the typology of texts. This was a form of opening up her handwritten practice to the world and its mechanical forms of textual communication and expression.

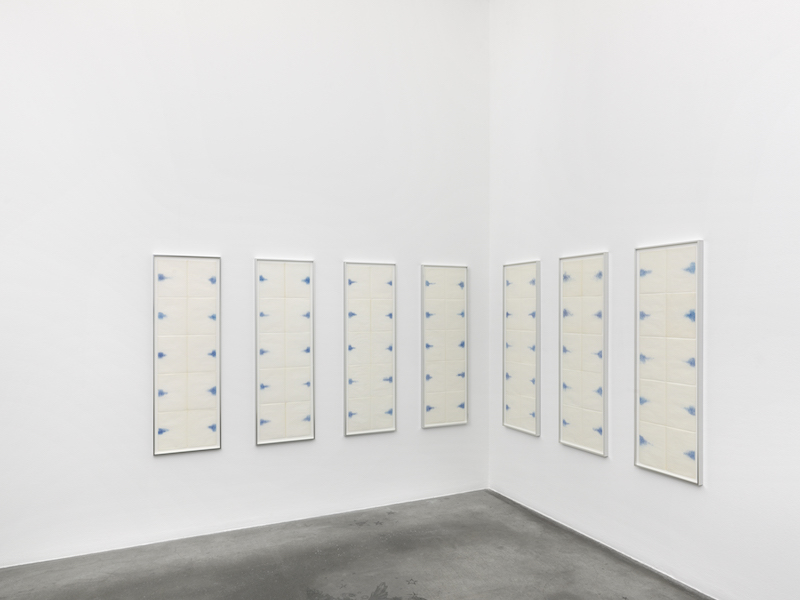

With these two seminal series, Irma Blank started a process of cyclic work, responding to inner explorations but also to external events. She considers herself a visual artist who “always started from the book” (and, in fact, she made over 100 handmade artist books, plus editions) and, for her, the whole work is ‘about the same thing,’ namely the exploration of the line of asemantic writing through different forms, whether with the tools of drawing, painting or as computer program. In her latest series ‘Gehen, Second life’ (started in 2017), she still works with the aim of communicating without words, existing without focusing on any specific meaning but that of the pure energy of being here, reconnecting with the action of emptying the sign through the repetition of a drawn line.

Irma Blank: ‘Gehen, Second life’, 2017-19, installation view at MAMCO Geneva // Courtesy of the artist and P420, Bologna, Photo by Annik Wetter

BAL: She has described her script as a method of transcending the meaning of language. She offers the viewer words as a visual experience. What effect does this have?

JC/JPRN: This is really up to the spectator but we have experienced, by now, several exhibitions of Irma Blank’s work in different contexts, and with different museum teams. One of the things that is clear, every time, is that, while one could fear the effect of the work to be hermetic, almost uncommunicative, it turns out to be the exact opposite. There is an interesting efficiency of the work, in the best sense of the word, that proves Irma Blank to be right about the need to go beyond words. People are moved, engaged, and they stare for a long time at those structured, nervous or calm lines that she makes. We are connected with the limits of verbalisation – and who hasn’t experienced that with a loved one, with a stranger, or even with oneself? When one immerses oneself in ‘Irma Blank,’ the exhibition, one realises that her work is not a steady progression towards self-control. On the contrary, it is a balancing act towards a meditative and ascetic state. But the drawings are ways to get there, they are not a lesson to the viewer and we think that people understand that. The pink ‘Eigenschriften’ are restless and exciting, whereas the blue ones are more contained, more well-behaved. But at the end of the day, all her work is about time – about its passing and its enduring. We are all submitted to time and, with her painstaking process, she makes it tangible, sometimes with acceptance and other times with a deep search for that acceptance.

BAL: How does Blank’s work contribute to the context and scene of artists who work with writing and/or script?

JC/JPRN: Irma Blank has been intermittently part of the avant-garde and contemporary art scene. In Italy, she certainly had an impact and an importance, especially, nowadays, for a new generation of curators who really adore her and respect her work. But what is to be praised, is that in those periods where she wasn’t really part of a scene that she nevertheless belonged to, from conceptual to informal art, she kept on working relentlessly. This is proof, if one needed it, that her work is really indistinguishable from her life. For her, to work is to live and vice-versa. Nowadays, we see artists from our generation react to her work with immense praise, which we think is what this touring exhibition will end up bringing. Irma Blank did not yet get the recognition she deserves and we are working hard for that to happen. The catalogue accompanying these touring exhibitions is going to contribute to that.

BAL: The exhibition at MAMCO spans decades of Blank’s work, connecting her first series to her last. Tell us about the thought process behind selecting the works exhibited.

JC/JPRN: The exhibition ‘BLANK’ consists of 8 shows in total, thoroughly exploring Irma Blank’s life work, and each iteration examines an aspect of it. For MAMCO, we focus on the more intensely graphic explorations of writing. We present her first two series ‘Eigenschriften’ and ‘Trascrizioni,’ spanning over 10 years of work, from the late 60s to the end of the 70s. Then, we leap to her two latest series, starting in 2000: ‘Global Writings’ and ‘Gehen, Second life’ (started in 2017). ‘Gehen’ means ‘to move forward’ in German.

This connection of her beginnings and her last series (as she says herself) is almost a philosophical statement: it shows how different and yet similar her research is, it illustrates that her line of life is deeply connected with her mark-making. It also demonstrates how, in its universal and ascetic form, the work also incorporates its time and particular events, such as isolation or illness.

We also included a video of the reading of ‘Splitter’ (2012), which is part of the ‘Global Writings’ series; in it, she reads a sequence of German words chosen for their sound rather than their meaning – a compelling exercise, considering she chose her mother tongue. The deconstruction of writing typical of her first series is also at play here, as the letters and words no longer convey meaning, shedding their intrinsic value, as did the abstract signs in earlier works.

Irma Blank: ‘Global Writings’, 2015, installation view at MAMCO Geneva // Courtesy of the artist and P420, Bologna, Photo by Annik Wetter

Exhibition Info

MAMCO GENEVA

‘Irma Blank’

Exhibition: Oct. 09, 2019 – Feb. 02, 2020

Rue des Vieux-Grenadiers 10, 1205 Genève, Switzerland, click here for map