Interview by William Kherbek // Jan. 10, 2020

Richard Brautigan’s techno-utopian poem ‘All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace’ (1967) will read to many in the age of Youtube bedroom Nazis, Amazon door cameras connected to police stations and tailored newsfeeds from Facebook as unintentionally hilarious. The idea of “all” of us being “watched over” by machines, whether they be of loving grace or not, is at best an ambiguous proposition in the age of the MQ-9 Reaper drone. The notion that technology might provide the path back to Eden may have looked feasible in the Summer of Love, but the world—and, indeed, California, where Brautigan was writing—looked very different at the time. In the ensuing half century, the machines have undeniably started watching us, and they don’t always like what they see. The integration of technological surveillance into every aspect of life has increased at a pace that would have been unimaginable to the rather quaint machines Brautigan had in mind, as they maintained a kind of Wordsworthian homeostasis in the “cybernetic meadow” over which they watched.

Yuri Pattison: ‘Light Therapy’ from the series ‘Sleep Industry,’ 2019, on view in exhibition ‘Our Happy Life’ at Canadian Centre for Architecture // Courtesy of the artist

Yuri Pattison’s technologically-concerned works have frequently posed the question of who will watch our watchbots. Pattison has recently explored the ways in which robotic management of data has played a role in aspects of wellness from managing sleep cycles to examining and assessing health information from app users. As the wellness industry increasingly makes use of machine cognition to sell “solutions” to users, the proposition of having one’s biological systems watched over by machines is as disturbing as it is unavoidable. Following the recent exhibition ‘Our Happy Life’ at Montreal’s Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA), we spoke to Pattison about the frontiers of cyber-wellness and how robotic oversight is altering our understandings of the inner and outer worlds of human beings.

William Kherbek: Could you tell us about the background behind your series ‘Sleep Industry’ commissioned for the CCA exhibition?

Yuri Pattison: For a number of years I was doing research into various types of light treatment systems, especially as they were being integrated into screen-based technology. There are a bunch of things that are quasi or pseudo-scientific, and one of the works I made during that time referenced a phenomenon that happens semi-annually at MIT called “MIT-henge,” which taps into a longer lineage in terms of the relationship between technology and the sort of New Age movement. Within MIT there was a phenomenon discovered where the sun lines up with one of the longest corridors on campus called The Infinite Corridor, and it’s been used for various experiments because of its length. Tom Norton, who was an architecture research affiliate at the time, discovered that the sun aligns with it twice a year in a similar way to sites like Stonehenge or New Grange in Ireland—and it’s a coincidence, it’s not by design—but someone produced a poster and popularised this phenomenon. I made a work that examined the history and the current celebration of that event.

I also became aware of the research around other aspects of light. One that was pioneered at MIT was related to sleep onset chemicals that are released by the human body and in other mammals when they’re exposed to sunsets. That research relates to the dosing of melatonin, and it pioneered the industry that became the melatonin supplement market. I combined those things into an early work related to sunset and the mixing and conflating of things I saw that were, perhaps, interestingly oppositional; for example, the fact that MIT is such a science and rationality-led institution, yet they were celebrating this kind of neo-pagan event. I was trying to make a complete work that negotiated these new traditions, and how they can have knock-on influences within industries and within communities, and I was seeing that more and more how consumer technology has become much less of a rational tool and something that’s marketed in mystical ways.

Yuri Pattison: ‘Light Therapy’ from the series ‘Sleep Industry,’ 2019, on view in exhibition ‘Our Happy Life’ at Canadian Centre for Architecture // Courtesy of the artist

WK: As these technologies advance and more information is available to people about their own biological processes, there is a curious dichotomy emerging: people have more information, but they are also more susceptible to manipulation and false contextualisations of the information by digital grifters and data brokers. Could you describe some of the ways in which health information is increasingly made available to potentially vast numbers of people via contemporary “health” and “well-being” devices, and how this form of pseudo-empowerment features in some of the works on show?

YP: Previously we thought of health in a very personal way. In relation to these technologies, I became more aware that they were focussed on being productive. Everything was tied to productivity and the externalised markers and metrics of productivity. I began to see it more as a nefarious extension of our value to the market, our value within the workplace. In that sense, all these ideas of health—particularly as built into technology—are things that I began to touch on and explore. For the CCA works I was expanding some research I’d done in other areas. I’d done a lot of research into light technology related to colour temperature, and there are a few papers about LED light, which produces very blue light, and how it could be quite damaging to the eyes, but also to sleep cycles because it suppresses sleep onset. Research has been done about shifting these blue lights into other spectra. I began looking at other related applications of this. A lot of these aspects of research go back to staging and entertainment, like in Las Vegas, where you have lighting and other things deployed to extract finances from you. They’re meant to keep you awake and in the casino, gambling. The longer you are there, the more they can extract from you.

There’s also the fact that these data are never really private. Previously, one of the most private times was your sleep, but now things have changed with the emergence of apps that track your sleep and are networked on the cloud and plugged into other systems, as we’re seeing with insurance companies “gifting” you a Fitbit and offering preferential rates on your insurance premiums if you’re more active. It’s a way of thinking about human existence as a natural resource to be mined or extracted by these companies.

Yuri Pattison: ‘Sound Therapy’ from the series ‘Sleep Industry,’ 2019, on view in exhibition ‘Our Happy Life’ at Canadian Centre for Architecture // Courtesy of the artist

WK: Increasingly, sleep is becoming one more form of labour.

YP: Again, this new idea of extraction comes from platform capitalism, where the labour and ideas of labour are much more performative. In relation to co-working spaces, the labour is often totally perforative, and most of the work happens in people’s homes and other locations, and these spaces are mainly places for having visibility, but the actual work happens in hidden spaces. This duality of the staged and the hidden is often present in my work.

WK: As the exhibition takes place in a space devoted to architecture, the notion of interfaces and design are important as well. Could you talk about the ways in which design—be it chemical design or product design—featured as elements of the show?

YP: In the heart of this show is a work from ‘sunset provision’ (a show I had in Dublin in 2016), where I presented two floor-based sculptures that utilised memory foam, memory foam mattresses, or sleeping aid material, along with other aids for sleep or wellness, therapy masks that claim to do everything from fix your complexion to aid with seasonal affective disorder. I presented those with various sound-masking systems, objects designed to create white noise, to create the atmosphere of the modern world in a more controlled or heightened way.

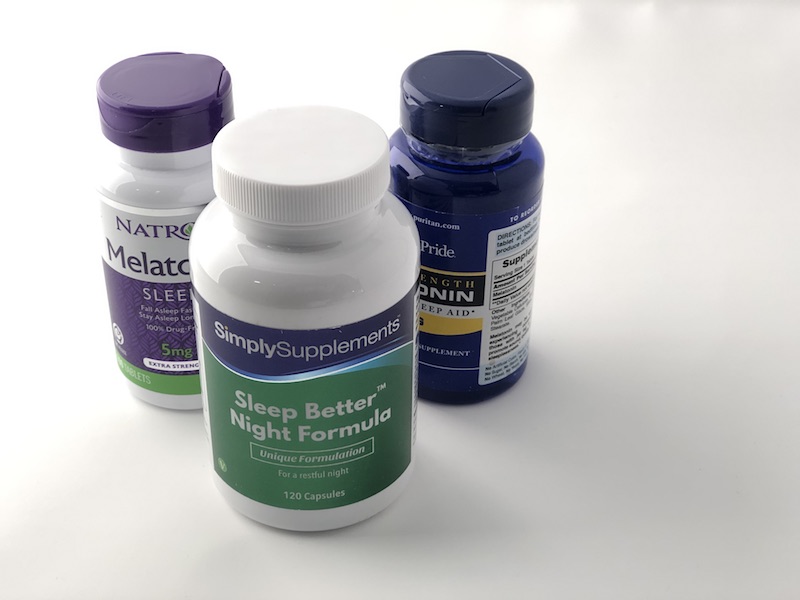

In Montreal, it was about presenting these designed objects in images that are deliberately overloading. They’re meant to contrast these different technologies by presenting several into the frame, when normally the experience would be that you’d buy just one of these objects. You pick the best rated one on Amazon, or you send it back and you buy another one. So the research kind of allowed me to do a mini-review, leaning into purely the aesthetic and design aspects rather than the practical. The companies present research, but they also present the aesthetic tropes. I bought a very wide selection of these devices—I think about 20—and I photographed a portion and, interestingly, what I discovered was that the idealism, or the presentation of them as a magic fix for certain problems, relied very much on branding and the external design of these objects. I opened up a lot of them, and they all run on pretty much the same circuits. Some of them had exactly the same components. They were just dressed up differently, often with drastic differences in price point.

Yuri Pattison: ‘Memory Foam Remembers’, 2016, installation view ‘sunset provision’ at mother’s tankstation, Dublin, Ireland // Courtesy of the artist

WK: Lastly, as it’s January, and a time of reflection for many people, could you maybe speak about the ways working in the art world has affected your own relationship to sleep? Does the level of travel you take on impact your ability to work to the best of your abilities? Are there aspects of the way art is presented and circulated that you feel could do for some revision and reconsideration?

YP: Time zones have kind of been dissolved for a lot of freelance workers. There’s a huge amount of migration, but for some skilled workers, particularly those who can work online, you have less physical migration and more body clock migration, where you work in a different time zone. You see this on outsourcing platforms, Amazon Mechanical Turks but also Fiverr or Freelancer.com, you see people working across time zones or at very strange hours or doing very strange shifts. Obviously this is nothing new, but it’s been accelerated in recent years, particularly the appetite certain portions of the world have for piecemeal cheap labour.

I think the art world, for all its pretension of ethics, definitely mirrors some of the worst aspects of capitalism, especially in relation to work and the expectations of work. It mirrors ideas that are imposed from freelancing: you’re doing what you like, so you should feel lucky. You should treat this as a vocation. You should always be available. The art world does that not just in terms of travel in my experience, but the expectation to always be available that extends to email response times and scheduling of calls. All these different aspects encroach on the personal, and this extends beyond artists, it’s relatable to all types of art workers.

Yuri Pattison: ‘Supplements’ from the series ‘Sleep Industry,’ 2019, on view in exhibition ‘Our Happy Life’ at Canadian Centre for Architecture // Courtesy of the artist

This article is part of our monthly topic of ‘Wellness.’ To read more from this topic, click here.