by Hannah Carroll Harris // Mar. 12, 2020

Being submerged in an underwater sound bath in the basement of a Berlin club may not seem like the most meditative experience, but somehow—sitting on the floor alongside a hundred other people on a Sunday night—I found myself entranced by the experimental sounds of ‘Oneironautics’. Installations of coral and seaweed, low-hanging lights and shiny streams of silver foil transformed the downstairs space at Arkaoda, creating a suitably subaqueous space. Curated by Diane Barbé, ‘Oneironautics’ took as its starting point the idea of a lucid dream and brought together the work of visual artists and musicians to guide us through an underwater voyage of striking visuals and dripping tones in a performance that sought to rethink sound spatialisation.

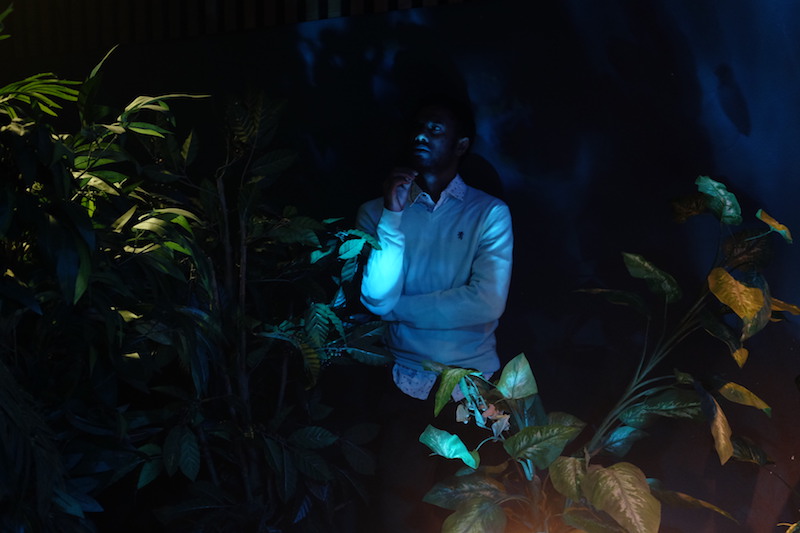

‘Oneironautics’ at Arkaoda, Sibi Abhimanue // Photo by Salomé Jashi

If oneironautics is the ability to travel consciously within a dream, the offerings of these artists had the uncanny ability to make us feel like an oneironaut. The evening began with the light and polyphonies of Vaguement Ensemble, a collaboration between experimental electronic artists Diane Barbé and Farah Hazim, vocalist and set designer Celia Stroom, vocalist Sibi Abhimanue and light designer Teresa Bartůňková. Combining experimental electronic sound with acoustic vocals, the performance traversed some unexpected—and sometimes overly obvious—oceanic soundscapes.

‘Oneironautics’ at Arkaoda, installation by Celia Stroom // Photo by Salomé Jashi

As the lights fluctuated with the ebb and flow of distorted synths, we began with what verged on the anticipated: distorted whale-like calls and haunting vocals, representing the more familiar reaches of the sea. However, as we were gradually brought into darkness, the sounds and lights converged into lesser-known territory. Overhead, small purple bulbs started to flicker and the synths became increasingly muffled, as though we had finally reached the darkest depths. When so much of the ocean is still uncharted, those that live in the deepest regions take on an alien-quality. Here, we were brought to a space of deep-sea microorganisms glowing with bioluminescence. Noise pinged from different corners of the room and we could feel the vibration of the surrounding speakers. The coming together of sound and light effectively conjured what is, for the most-part, an unimaginable world.

Another similarly impressive moment came when we began to ascend back Earth-wards, as the spectral vocals eventually returned. Spotlights cleverly staged throughout the space sent beams of light around the room. Through the smoke, as the dappling light refracted off the silver foil, we truly got a sense that we were resurfacing, just as light might filter through the water from above. It was in these moments where we became acutely aware of our bodies in relation to space, but in a distinctly more liquid way than we are used to.

‘Oneironautics’ at Arkaoda, Wissam Sader and Laure Boer // Photo by Salomé Jashi

Following on from this, Laure Boer and Wissam Sader created a spatialised live set using acoustic instruments and electronics. Through a dense yellow light, electronic strings and synths crescendoed through a spectrum of sound like an infinite sunrise, letting us sink into its radiating tones. This continuous but ever-increasing lull entranced me to the extent that I was still transfixed when seemingly water-muffled acoustics were slowly introduced. The performer picked up an array of objects—what looked like a telephone, some foil perhaps—and began playing them into a microphone, dampened as though they were somehow underwater themselves. Reminiscent of the echo-location techniques used by dolphins and whales, we strained our ears trying to locate and identify the different sounds, aware of the translucent white quartz bowls of varying sizes laid out on the floor adjacent.

‘Oneironautics’ at Arkaoda, Kosmoklang (Pina Rücker) // Photo by Salomé Jashi

Gradually, the set transitioned into the serene vibrations of Kosmosklang (Pina Rücker). The artist knelt amongst these crystalline vessels, using various implements to create a hypnotic sound bath, striking and stroking different parts of the bowls to produce a resonant crystal hum. Traditionally used in spiritual and meditative healing sessions, the vibrational reverberation is thought to have a therapeutic quality and the performance contributed to the overall experience of spatially visualising the sounds of the oceanic underworld.

Although these explorations of aural liquidity undoubtedly had a calming effect on the audience—as people lay spread out on the floor, some clearly meditating—there was one aspect that made it difficult to reach the desired effect of achieving a lucid dream-like state. As oneironautics expresses the act of being able to consciously control your dreams, it was ultimately difficult to transcend as we were very much aware of our physicality, sitting on a cold, hard, concrete floor. These practicalities aside, I left feeling markedly lighter than when I’d arrived. If this were a recurring event, it would be one I would readily subscribe to, cushion in tow.

‘Oneironautics’ at Arkaoda, Farah Hazim and Diane Barbé // Photo by Salomé Jashi