Interview by Jack Radley // June 12, 2020

Allison Janae Hamilton triangulates her artwork between her Kentucky birth, Florida upbringing and Tennessee family farm. The swamps simmer beneath skewers of skinny pines. The crickets commandeer conversations. The winter solstice signals family birthdays, when the light extinguishes like the candle of a coveted wish. While Hamilton’s work draws on her own experiences of the American South, from Baptist hymns to hunting rituals, her practice in no way stands to document it. Instead, through a marriage of southern folklore and personal mythology, she imbues her landscapes with a mystique from which we can extract our own questions.

In Hamilton’s environments, we recognize tales from terrains unknown, not from landmarks, but from common connections of crisis, labor and joy. In her work—spanning photography, performance, sculpture and installation—the storm of a hurricane brings brewing social inequity to the surface. We understand climate change through individual snippets of Southern life, as stories supplant statistics. Hamilton splits her time between New York City and Northern Florida, where she typically works during the winter. As landscape enters atmospherically into everything Hamilton does, it was apropos for nature’s noises to color our phone conversation, right before a hurricane.

Portrait of Allison Janae Hamilton // Photo by Frankie Alduino

Jack Radley: Let’s start simple. Where are you?

Allison Janae Hamilton: I am in Northern Florida right now. My family lives right at the top of the state in an area called the Big Bend, also known as the Red Hills. Leon County. It’s a part of the country that I think most Americans don’t even know about. When most people think of Florida, they think about South Beach or Disney World, but this part of Florida is definitely more like New Orleans, Charleston, or Savannah in terms of the landscape. It’s got the live oaks and Spanish moss, with more of a swampy kind of vibe to it. It’s the part of Florida that is “the South,” which is ironic because culturally the more north you go in the state, the more southern it is.

Usually I spend my winter down here with my family; I usually spend Christmas with them and then stay another couple of months and work. I live in Manhattan and my studio’s in Manhattan; I had just gotten back to the city when everything started happening with COVID-19. I decided to come down South in mid-March and wait out the pandemic down here.

Forgive me, I’m actually outside right now—we have a thunderstorm coming, so I had to get out and walk the dog, but it should be pretty quiet; I don’t live in a high traffic area. And, as I say that, of course, a car passes me.

Allison Janae Hamilton: ‘Brecencia and Pheasant III,’ 2015, Archival pigment print, 61×91.4 cm, Edition of 7, with 2AP // Courtesy of the artist and Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York and Aspen, © Allison Janae Hamilton

JR: Is the work you make in your Florida studio fundamentally different from the work you make in your Manhattan studio?

AJH: The work is in different stages of my practice. Down here, it’s just part of the culture that the landscape is imposing—it’s in charge, really. In the winter, everything is a little bit more dormant. We have the big reptiles, gators and all that; I do a lot of shooting [images] out in the river, and it’s just a little bit safer. I’ll shoot down here, and then I’ll bring everything back to New York and edit up there.One thing that I appreciate about my particular practice lifestyle-wise for me is that I work in so many media that there’s always something I can be working on, no matter what location I’m in; I lucked out in that way just by virtue of having an interdisciplinary practice.

That said, being here and being immersed is important for me, and it’s important for the practice, because I need to be in the environment that I’m drawing from. I’m curious to see what’s going to come out of being here at a different time of year than I’m used to. There’s a lot that I actually forgot about the area during this transition from spring to summer. I forgot just how overpowering the magnolias are down here, since I’m usually in NYC during the spring.

Allison Janae Hamilton: ‘Three girls in sabal palm forest III,’ 2019, Archival pigment print, 61×91.4 cm, Edition of 5, with 2AP // Courtesy of the artist and Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York and Aspen, © Allison Janae Hamilton

JR: One of my favorite things that you write about your depiction of landscape is that “the natural environment is the central protagonist, not a backdrop.” It sounds like nature is taking charge right now.

AJH: Yeah it is. That’s my own framing: what if we looked at landscape and its history and symbolism, but also looked at how that has structured our world socially in so many ways? I’m coming from the places I know most intimately, which are Florida and rural Tennessee. You look at the way that landscape has been so much a part of the social formation of this country, for better and for worse. If you look at landscape, there’s really a lot there: access to different types of space, land loss, migration (forced and otherwise), property, materials of labor, and what’s been mined for economic, cultural and spiritual uses by communities at the margins, like medicine and hoodoo. It’s a very complex terrain, in a physical and metaphorical sense.

I use the drama of the landscape as an affective mechanism to try and trigger an emotional response in the viewer. In the summer, every afternoon can be thunderstorms: there might be ten or fifteen minutes like the middle of a hurricane and then boom—it’s like someone turned the lights back on, and the birds come out and everything’s fine and bright. I’m very drawn to epic myths and stories on the scale of the hero’s journey. The blue and green are so bright in Tennessee around the solstice time—the colors look like crayons. Around Thanksgiving, the cotton there is just everywhere as it falls off the cargo trucks heading to processing: it gets on your shoes and stuck to your car, it’s like snow. There’s a lot of drama and these remnants from a very long history of the land that’s always in your face all the time.

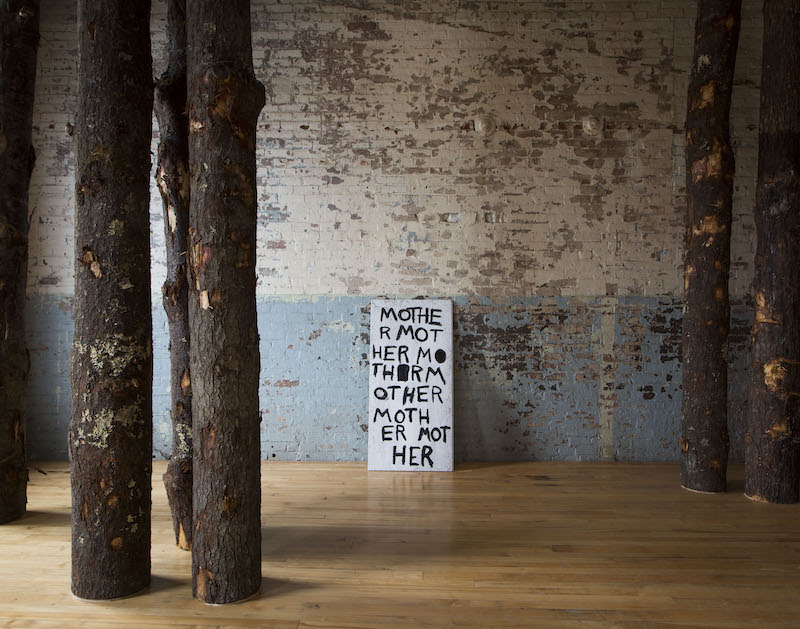

Allison Janae Hamilton: Installation view ‘Pitch’ at Mass MoCA, 2019 // Photo by David Dashiell

JR: I hear some birds in the background, too. I would love to discuss the sonic components of your work.

AJH: I grew up in the Black church in the South, a pretty quintessential southern, Black baptist experience. That sonic impulse was a huge part of my childhood soundscape, which also has a lot of drama in it, a lot of crescendo, rising and falling. It’s always been something I tap into: the cultural music legacy that comes out of these interactions with the land, many times arduous, and the sounds of the environment, which are all-encompassing. A lot of times, especially in my installations, I try to tap into that feeling: how you feel when you go out to the swamps, rivers, and lakes in a tiny little kayak or fishing boat and you’re surrounded by this very dramatic soundscape.

The show that I did at MASS MoCA I called ‘Pitch’ for three reasons. I was thinking about the last breath of the natural turpentine industry in Northern Florida and South Georgia. I read one quote from a turpentine laborer who said: “We work from can’t to can’t,” which is “can’t see in the morning” to “can’t see at night.” They worked long before the sun goes up, until after it goes down. I was thinking about “pitch” in terms of the sounds of the natural landscape, and also “pitch darkness,” and also pitch as in music and work songs and some of the cultural utterances that Black people have created under such exploitative regimes of forced labor.

Allison Janae Hamilton: Installation view ‘Pitch’ at Mass MoCA, 2019 // Photo by David Dashiell

JR: You currently have work in ‘Photography and the Surreal Imagination’ at The Menil Collection in Houston. Let’s talk about the dramatic juxtapositions in your work, and how you see its relationship to surrealism—with or without a capital ‘S’.

AJH: Being in that show was a really interesting opportunity for me to think of my work in that way and that part of history. When I’m making work, I really don’t think much about the art historical canon or the impulse creation of surrealism; I’m thinking about my own cultural forms and aesthetics. I’m thinking more along the lines of hoodoo—which I guess you could call “surreal”—but I’m thinking more of a U.S. Black American formal connection. I’m just pulling from all of the stuff that I know, all the stuff that I grew up hearing. I’m kind of looking at a completely different tradition.

Allison Janae Hamilton: ‘Scratching the wrong side of firmament,’ 2015, Archival pigment print, 61 x 91.4 cm, Edition of 5, with 2AP // Courtesy of the artist and Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York and Aspen, © Allison Janae Hamilton

JR: I think people try to read Art History as a linear progression of artists revisiting the same themes and motifs, but the discipline has ignored so many narratives and exchanges that these purported pedigrees from its myopic canon fall flat. I’m thinking about your photograph ‘Scratching at the Wrong Side of Firmament’ (2015). Someone could read the masked figure in connection to Magritte’s veiled faces, but considering your scholarship on the carnivalesque, to me the work feels more in conversation with Gladys Bentley than André Breton.

AJH: Exactly. The carnivalesque is an interesting mode for me: this idea where this normal social order gets disrupted, there is playfulness and chaos in that. That’s what Mikhail Bakhtin was writing about, but you can look at that in an African diasporic sense. We have carnival in pretty much every part of the diaspora, from Brazil to the Caribbean to the US. For me, I’m pulling from that idea but I’m bringing it back into the context that I know. I’m either playing with or mixing those established canons with something else, or just privileging my own cultural forms. I do that with the yard sign pieces, drawing from vernacular yard art. I don’t want to duplicate or replicate anything 1:1 or to be documentary. That’s never what I’m trying to do. It’s more privileging those utterances as forms that I can draw from.

Allison Janae Hamilton: Installation view ‘Pitch’ at Mass MoCA, 2019 // Photo by David Dashiell

JR: How would you situate your work within climate change conversations?

AJH: What’s important for me is that I don’t look at climate change solely from a perspective of the numbers, but that I look at it from the perspectives of people. Climate change is not something that’s coming for everyone equally. For example, ‘The peo-ple cried mer-cy in the storm’ (2018)—a site-specific piece I created for Storm King Art Center—looked at the ways natural disasters illuminate and expose the social disasters that are already in existence. Whether that’s Hurricane Katrina, Hurricane Maria, the 1900 Galveston Hurricane, the Great Miami Hurricane of 1926, or the 1928 Okechobee Hurricane, from which thousands of Black migrant workers died buried in mass graves unmarked until recently and which was the backdrop of Zora Neale Hurston’s ‘Their Eyes Were Watching God.’ You see all the ways people of color are treated ‘in the aftermath of the storms.’ With climate change, what happens when the hurricanes get more frequent, more intense, and the season gets longer—who is going to be most affected?

You can’t look at climate change as something that’s neutral, the Unifier or the Great Equalizer. It’s not that. Even when quarantine started, I saw a lot of climate activists saying: “Oh isn’t it great that they environment is getting such a break and we’re all home in our houses cooking healthy foods, and we’re not out, we’re not using mass transit, we’re not in our cars, we’re not going anywhere.” The next image I saw right after that on my timeline was the image that Charles M. Blow posted of the NYC subway, filled, packed to capacity with predominantly people of color. Why? Because they have to go to work. Because they do not have the luxury of staying home and having all this down time. I think there’s a disconnect with a lot of the ways those conversations go.

We need to really recalibrate the climate change conversation with what is happening socially. We’re not going to get the full story if we don’t look at how things impact people, how a disaster impacts different communities differently. That’s what I’m trying to bring into the conversation—not in a didactic way, but in a way that draws on these very real histories of landscape and tries to tap into these complex issues through immersion and affective resonance.

Allison Janae Hamilton: Installation view ‘Pitch’ at Mass MoCA, 2019 // Photo by David Dashiell

Allison Janae Hamilton: Installation view ‘Pitch’ at Mass MoCA, 2019 // Photo by David Dashiell

JR: There have been ongoing nationwide protests against the ingrained systemic racism, discrimination and abuse of power in this country. People are demanding accountability for the murders of Black Americans including Ahmaud Arbery, George Floyd, Tony McDade, Breonna Taylor and so many others. What has your experience of this past week been?

AJH: I’ve been deeply impacted by this week, the weight of which is impossible to adequately convey or translate. As a Black American, it’s personal. The first person of my generation who I saw murdered on film at the hands of the state was Martin Lee Anderson, a 14-year-old boy killed right here in North Florida. This was before YouTube took off, before hashtags, before social media culture was such an integral part of our lives, so despite his murder being documented on video, most people don’t know about his story. But it was a moment I’ll never forget. I was an undergraduate student in Tallahassee, and we college kids rallied and protested and sat-in to try and get justice for Martin Lee and his family. Horrifically, but not surprisingly, we couldn’t. Year after year, each name, each video, each protest since, brings back those memories. Tony McDade’s killing also happened here in North Florida. Breonna Taylor was from my birth state of Kentucky.

This article is a part of our Features’ topic ‘Landscape’. The themes in this topic are inspired by the exhibition ‘The White, the Green, and the Dark: Contemporary Positions from Norway,’ presented by the Royal Norwegian Embassy in Berlin, and aim to spark a dialogue with its curatorial framework. The exhibition explores concepts of identity and home through intimate portrayals of the region’s landscape, both ecological and social, using a wide variety of media from sound and film to textile and sculptural works. A further emphasis of the contemporary works on display is the presentation of works by artists who belong to the Indigenous ethnic group of the Sámi. To read more from this topic, click here.

Artist Info

Exhibition Info

Menil Collection

Group Show: ‘Photography and the Surreal Imagination’

Exhibition: Feb. 15–June 14, 2020

menil.org

1533 Sul Ross St, Houston, TX 77006, United States, click here for map