Interview by Alison Hugill // June 23, 2020

Britta Marakatt-Labba, a Sámi textile artist and painter, grew up in a reindeer-herding family in the Northernmost region of Sweden. For the Sámi, who have lived across the borders of the countries today known as Norway, Sweden, Finland and Russia for generations, movement across the land has always been crucial to their lifestyle, livelihood and agricultural practices. As such, Marakatt-Labba primarily identifies as Sámi, the constructed borders of specific countries becoming largely irrelevant. Her practice is deeply concerned with visual storytelling in relation to the community and the landscape in which she lives and works.

The Sámi “yoik”—a traditional form of song that is common across Sápmi territory—is one of the oldest continuous musical traditions in Europe. A yoik is a powerful form of cultural expression in the region and has been subject to attempts at suppression under various religious and state authorities throughout history. In her work, Marakatt-Labba seeks to transmit elements of this mode of storytelling, which have been passed along orally, into her intricate and captivating hand-embroidered textile works. Her 2007 piece ‘History’, which was presented at Documenta 14 in 2017, is a 24-meter embroidered narrative of the history of the Sámi people. We spoke to her from her home in the village of Övre Soppero—where she lives with her husband and son, both reindeer-herders—about the significance of this work, as well as how her role as an artist has changed since her early involvement with the foundational Sámi Artists Group in the 1970s.

Britta Marakatt-Labba, portrait // Photo by Petwin Sara

Alison Hugill: In the current exhibition ‘The White the Green and the Dark’ at the Norwegian Embassy in Berlin you show two works—a video of your textile work ‘History’ (2007) and a smaller embroidered piece, ‘Movement’ (2000). These works span 7 years of your career. How do they relate to one another?

Britta Marakatt-Labba: My work is like singing a Sámi yoik: there’s no beginning and no end. It’s like a circle. So with every piece I make, I’m thinking about stories and experiences from my childhood. I was born in autumn just on the border of Norway and Sweden. I was raised in a reindeer-herding family and we moved between Sweden and Norway, so I have one foot in each country. As Sámi, we don’t have any borders.

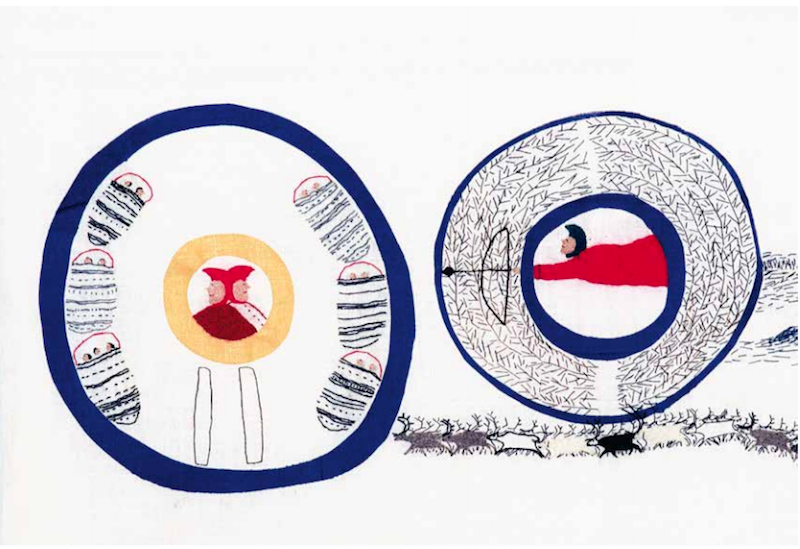

‘Movement’ is a reflection of my thoughts when I was young and my parents would work with reindeer. I don’t remember it all precisely, but my eldest sister has told me a lot about what it was like as we moved through the seasons: it was good to move in summer and autumn, but very hard in the winter.

Nowadays we move very fast. We have cars and helicopters to make things easier. ‘Movement’ is like one bit of that history. But then, later, came ‘History,’ a 24-metre narrative about Sámi history from its early beginnings. When people speak about our area, they often talk about a part of Europe that is desolate, where there are no people. But we have always been here. And we are still here in this place. It has never been empty here.

Britta Marakatt-Labba: ‘Movement,’ 2000 // Courtesy of the artist

AH: The video of ‘History’ that you are showing in Berlin has a beautiful soundtrack of yoiking, as well.

BML: The yoik that you hear on the video is my father’s yoik. Yoiking was forbidden when Christians came to Sápmi. The yoik tells us a lot about who a person is, how they behave in this life. My father’s yoik has a lot of words; he was a very clever reindeer-herder.

AH: What is your relationship to the Sámi language today?

BML: It’s my mother tongue. We speak North Sámi every day. I have also taught it to my son. English is my fifth language. Language, for me, is just like making art: if you put up walls in front of you, you’ll stop trying to speak. I always say: “Just talk! Just make art! Nothing you do is wrong.”

AH: Storytelling is an important part of your practice. There are a lot of different narratives in your large-scale piece ‘History’. What kind of process went into that work?

BML: It was KORO in Norway that commissioned the piece. I knew they would install it at the university in Tromsø. I chose embroidery to tell the story. I wanted to start with nothing, just forest, and then add the different animals that you find in this area. From the beginning, the Sámi were hunters. And then we learned to work with reindeer. But we are not only reindeer-herders, we have different expertise like fishing and agriculture, too.

I also felt like I wanted to include some political events. So I included the Kautokeino Rebellion of 1851 when Sámi people protested against the authorities and, in the end, two Sámis lost their heads. It was a really dark period in our history. A local merchant, who sold alcohol to the Sámi, was the initial target for the rebellion because they believed it was wrong for him to distribute alcohol to our people.

This story is just one part of the artwork. I walk through the history, and it ends with the institution of the Sámi parliaments in Finland, Sweden and Norway.

Britta Marakatt-Labba: ‘History,’ 2003-2007, detail, 24m embroidered textile // Courtesy of the artist

AH: You were part of the Sámi artist group Máze and helped to found the Sámi Artist Union in the 1970s. What impact did that sense of community in the arts have on your work?

BML: When I started to work with these storytelling pieces I was thinking about the Inuit people of Greenland. They have a long history of art based on storytelling. As Sámis, we had less of that, we had a primarily oral tradition. I felt like I wanted to leave something after me.

During the period of the Máze group, we had lots of exhibitions together. It was much easier to have our voices heard and to get Sámi art out to the world when we were a part of a larger group. It would have been very heavy if I was all alone.

I had begun thinking about these storytelling pieces long before I even knew what material I could use to make them. Before I began studying art in Gothenburg, even. I tried everything: I painted, I worked with lithography, I tried weaving. One day when I was dying yarn, it finally clicked: I would use the technique of a painter, but instead of paint I would use yarn.

Britta Marakatt-Labba: ‘Tapaus ajassa / Event in Time,’ 2013, textile // Photo by Hans Olof Utsi

AH: You spoke about the heaviness or the individual burden of trying to tell the story of a people, of trying to represent your people through your art. I imagine this was even more difficult 40 years ago.

BML: Yes. It was not easy to be the first ones to break through as Sámi artists. People were laughing at us. The stereotype of artists at that time was that we just smoked and drank a lot. But that wasn’t true: we worked incredibly hard. We trusted in ourselves and we believed we could do something good for Sámi society. Today, we can finally see the fruits of that labour. There are lots of people around the world interested in our art.

It’s not easy to be in my situation right now. If this interest had happened 20 years ago, it would have been much easier for me cause I was much younger. Now I am nearly 69 years old and we only have 24 hours in the day. It’s hard to meet the constant demands. After the presentation of ‘History’ at Documenta in 2017, it was a real shock for me to have so much international attention. People really took that piece to heart.

Britta Marakatt-Labba: ‘Tapaus ajassa / Event in Time,’ 2013, textile // Photo by Hans Olof Utsi

Britta Marakatt-Labba: ‘Climate Change,’ 2007 // Photo by Hans Olof Utsi, Courtesy of the artist

AH: In addition to textiles, you work with watercolors and lithographs and you have illustrated books and designed costumes and sets for plays. What paths is your practice taking now?

BML: At the moment I’m working on the movement of Kiruna city, where fractures in the earth from ore mining are threatening the residential areas and have forced many inhabitants to move their houses. A few days ago there was an earthquake in Kiruna. The future of the city is uncertain, they are beginning to build up a whole new city. The Swedish mining company LKAB are boring holes into the middle of Kiruna. For me, it’s so important to talk about what’s happening with the Earth right now. In terms of climate change, I am thinking about the ways that one thing affects another, the cyclical nature of events. When you cut down forests in Brazil, the climate will change here where I live, too. Just like in my work, it all comes full circle.

This article is a part of our Features’ topic ‘Landscape’ and is presented in collaboration with the Royal Norwegian Embassy in Berlin on the occasion of their exhibition ‘The White, the Green, and the Dark: Contemporary Positions from Norway,’ in which Britta Marakatt-Labba is a participating artist. The exhibition, curated by Sabine Schirdewahn, explores concepts of identity and home through intimate portrayals of the region’s landscape, both ecological and social, using a wide variety of media from sound and film to textile and sculptural works. A further emphasis of the contemporary works on display is the presentation of works by artists who belong to the Indigenous ethnic group of the Sámi. To read more from this topic, click here.

Artist Info

Exhibition Info

Royal Norwegian Embassy

Group Show: ‘The White, the Green, and the Dark: Contemporary Positions from Norway’

Exhibition: June 2–Oct. 3, 2020

nordischebotschaften.org

Fellehus, Nordic Embassies, Rauchstraße 1, 10787 Berlin, click here for map

Galleri F15

Group Show: ‘Earth, Wind, Fire, Water’

Exhibition: June 16–Oct. 4, 2020

gallerif15.no

Albyalléen 60, 1519 Moss, Norway, click here for map