Article by Elizabeth Schippers // July 28, 2020

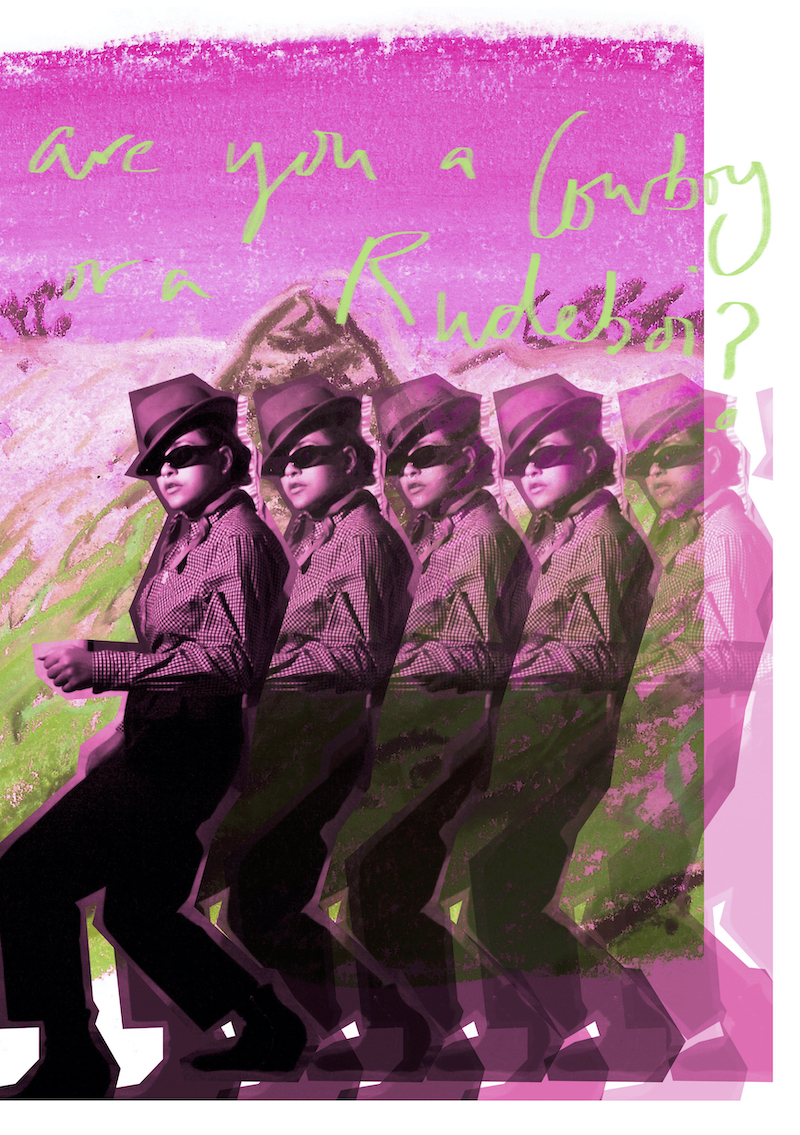

Victoria E Pullen is an artist and recent graduate from Chelsea College of Art living in London. With her recently created digital artist book, ‘“Victoria” to “Verlaine”’, she explores the ways in which we create modern myths surrounding subcultural practices in the music scene, art world and online fandoms. The artist book contains a multitude of subjects and identities: It reflects on the role of art and institutions in subcultural spaces, and practices of reappropriation that range from presenting art in club spaces to the reclaiming of the western cowboy as a Black and queer icon. As a whole, ‘“Victoria” to “Verlaine”’ constitutes a conversation between the artist and a self-created modern myth, the sum of fractured pieces. Our discussion follows the fragmented identities and spaces that are threaded throughout the book, held together by the relation between punk and fandom.

Victoria E Pullen: ‘“Victoria” to “Verlaine”’, UAL Graduate Showcase, Chelsea College of Art, 2020 // Photo by Victoria E Pullen

ES: Both your dissertation and ‘“Victoria” to “Verlaine”’ explore what you call “modern myth-making” and “subcultural identities”. Can you expand on the meaning of these concepts and why they are central to your practice?

VEP: When I was asking myself, “What’s the one thing that really means something to me, what do I care about?”, the answer was punk—which my dad introduced me to at a very young age—and subcultural identity. I began to see another form of psychological escape and freedom in creating and embodying this fantasy persona and environment that contradicts everything else in your known reality. The way we view punk and other 20th century subcultures, the way we romanticise and canonise them, is modern myth-making. By decoding the myths around these cultural moments, you unravel your own fantasy of what these youth movements really were, by working out how and why we remember them a certain way—or in my case, the phantom remembering of a period before my time, heard secondhand through stories and personal mythologies. Malcolm McClaren shaped punk with a carefully constructed narrative in mind, and so much has been lost by only ever using his lens to explore it.

In ‘“Victoria” to “Verlaine”’ I become my own Malcolm; I’m the puppet master and I play every part, I recall factual events that become fictional in their retelling, and I birth a new visual identity. As a Black woman who has eagerly shuffled through various rock music scenes populated by white people, there have always been uncomfortable tensions in my identity. I couldn’t make these things meet in the middle, but I gained so much personal insight by using my dissertation to confront the relationship punk, two-tone ska and skinheads had with Blackness and gender. ‘“Victoria” to “Verlaine”’ is a representation of that new understanding, and it’s a proud acceptance that I am the sum of many fractured pieces.

Victoria E Pullen: ‘“Victoria” to “Verlaine”’, UAL Graduate Showcase, Chelsea College of Art, 2020 // Photo by Victoria E Pullen

ES: You point towards a connection between punk and fandom. Can you elaborate on this connection?

VEP: Honestly, this is something that has landed me in several arguments outside bars with strangers who hated the very idea of it, but punk is fandom! All subcultures formed around music are inherently fannish, because it’s a community founded on a common appreciation for something that goes on to form its own localised culture through art, style, and language. For punk, that locale was physical—certain bars, clubs and gig venues—but even this becomes much more complex if you consider the hostile environment surrounding punks living outside of bigger cities. Fandom today largely occurs in online spaces, but you still group together on a small number of websites in niche communities, creating and sharing traditions. The mythologisation of fandom is due to its nature of thriving in the margins of popular culture, and in recent years, since moving from fanzines to the internet, fandom relies on its ability to circumvent copyright accusations, censorship and moral policing. In comparison to punk, it’s a much more organic and at times, mysterious, form of myth-making that prioritises the passing of information and artworks over the actual storytelling of how those practices create a collective identity.

Punk was responsible for the resurgence of fanzines in the UK and the DIY ethics inherent in punk are easily found in modern day fandom. What’s so different about circulating a photocopied zine about your favourite bands compared to writing about them online or posting artworks of them? The beauty of punk and fandom is the shared ideal of validating the amateur: No skill or experience is required to create and be appreciated; you don’t participate with the expectation or hope of becoming rich and famous; and both are controversially expressive spaces where you can contradict or criticise mass media and mainstream culture. One line I wrote that I still love is: “Punk as a collective movement is at heart, a fandom; and fandom, at its heart, is an anarchic rebellion against how we are supposed to interact with pop culture.” Most importantly, punk and modern fandom share a desire of creating an antidote to the monotony of mass culture, particularly the strands of fandom that use self-publishing and reactionary creation. There is an active yet defiant consumption of pop culture—one that reacts by appropriating those same channels to express experiences and identities that mainstream avenues refuse to acknowledge.

Victoria E Pullen: ‘“Victoria” to “Verlaine”’, UAL Graduate Showcase, Chelsea College of Art, 2020 // Photo by Victoria E Pullen

ES: How does this understanding inform your artistic practice?

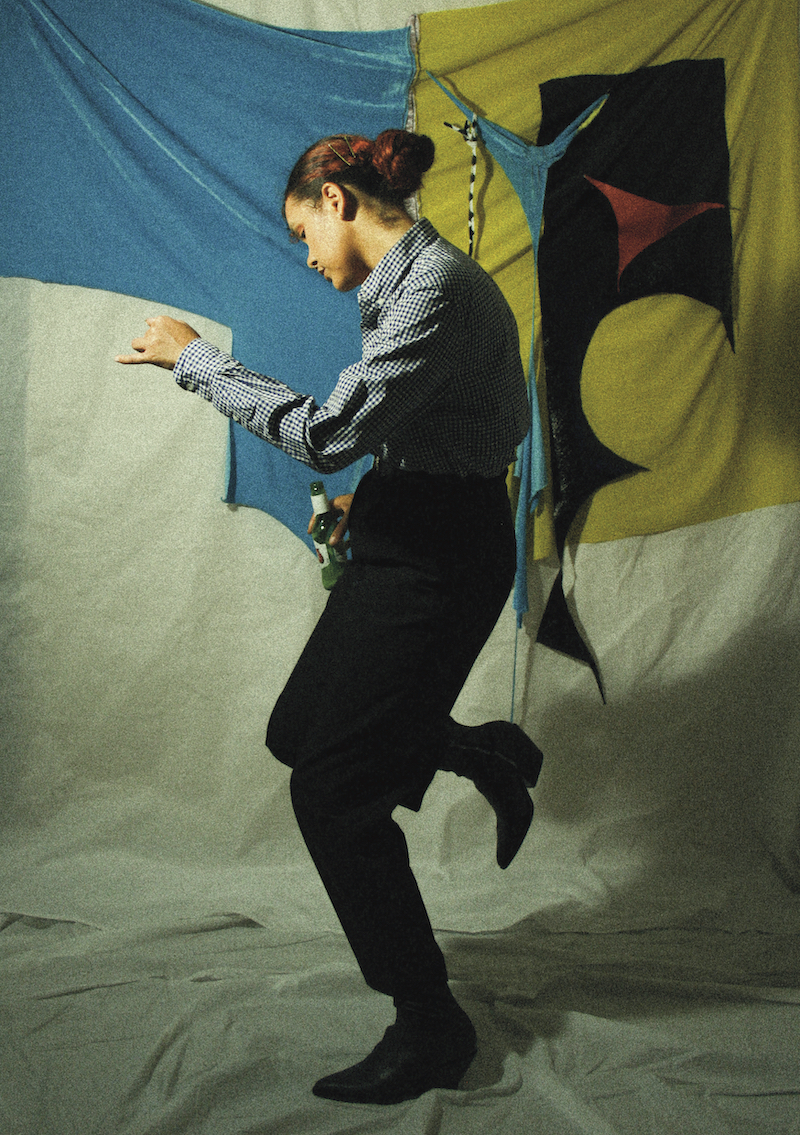

VEP: Before lockdown my practice was centred more around sculpture and installation. The process of making physical objects—the ideas of impulse, sensuality, repetition and repair—have always been important. I do favour DIY techniques that aren’t necessarily considered “fine art” to many people, like papier-mâché or slapping plaster over chicken wire. I like to learn through making and figuring things out for myself, and I think that’s something inherent in punk and fandom. You just dive in and pick it up as you go, because the conviction and message is more important than the way you did something. That’s exactly how ‘“Victoria” to “Verlaine”’ came to fruition, too. The idea of ska-inspired chequered chaps appeared like a ridiculous blip in my mind and I made them from scratch in a way that made sense to me after I failed to decipher a real pattern for traditional leather chaps. I find the best results in my work come from messing around and fumbling my way into success.

ES: What about your attitude towards art institutions?

VEP: I suppose this way of working has always made me feel like I’ve been wasting art school by not spending all my time in the workshops. I only started to see myself as an artist when I understood that the parameters of art are so much wider than we’re led to believe. It’s not a competition to be the best or the most inventive; it’s a vehicle to speak to people, to create meaning in a world where it feels like there is none, to take journeys of self discovery and let other people be a part of them, possibly even uncovering things about themselves through it too. I’m not going to bend over backwards trying to get a foot in the door of the “professional art world”, because that space is still heavily restricted by institutional gatekeepers. Even at art school, you see that a lot of the people who have more opportunities right from the start are white students with wealth or connections in the industry, and they’re the ones who can afford to take unpaid internships, are able to put more time and resources into their practice, and genuinely see commercial galleries as viable pathways.

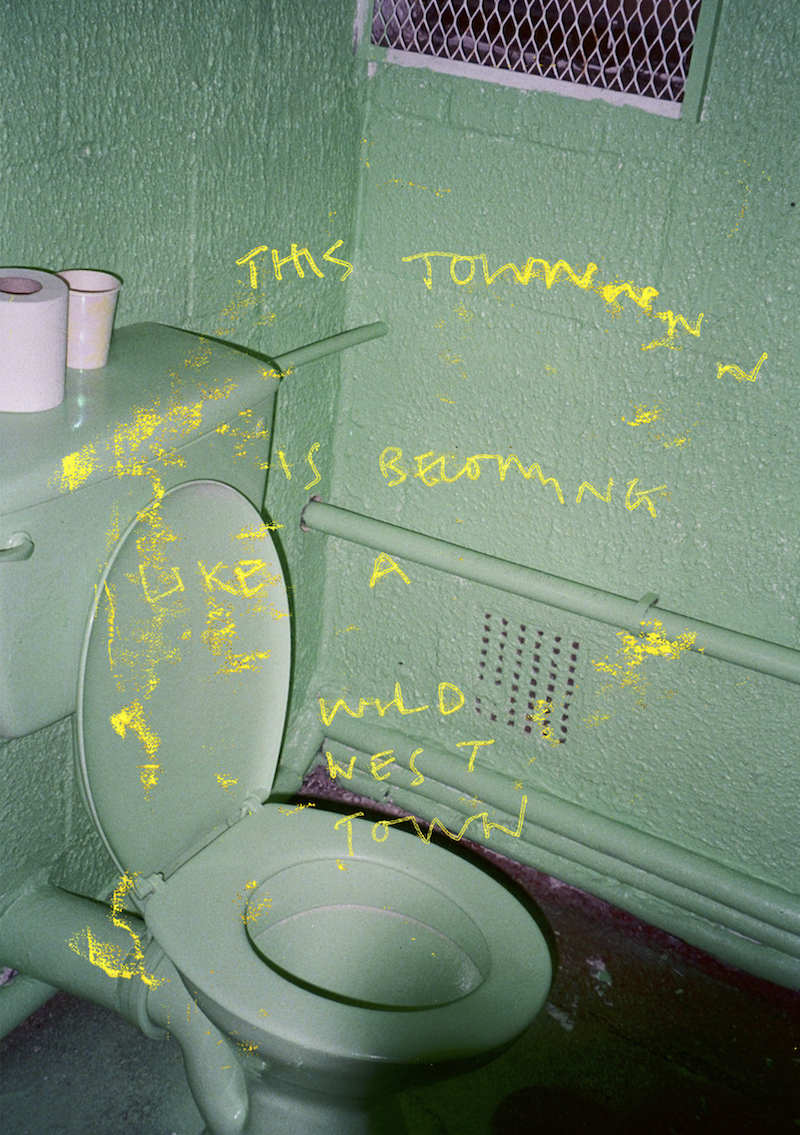

ES: A lot of your artwork reflects on public spaces, such as bars and clubs and their toilets, as unintentional, uncommon or untraditional “exhibition spaces”. What draws you to these spaces?

VEP: I became interested in the community element of nightlife and how integral the spaces of clubs and bars are to the enactment of subcultural identity and experience. It’s the place where music, style and performance are most elevated as personal signifiers. In many cases, I can’t remember the specifics of a past night out very well but I’ll have a great recollection of whatever happened in the bathroom. It just sticks. I also realised that I have an unintentional archive of photos taken in the toilets of bars and clubs since 2014—not just the writing on the walls, but the actual toilets themselves too. Suddenly the club bathroom becomes this site of intimate exchange, simultaneously public and private, where the individual and communal overlap. If the club acts as a stage for your fantasised identity, then the bathroom is backstage: It’s not a case of removing the mask, but instead giving this idealised version of yourself a moment of reflection and vulnerability. It’s the only explanation I have for those lovely pearls of wisdom you find scribbled next to the loo roll or the act of baring your soul for fifteen minutes to someone you just met because they said your hair looks nice. Better yet, I love when those kind of interactions happen via toilet wall, where conversations can be had without ever meeting the people involved, where you ask questions without expecting to read the answers, where jokes are made not for the satisfaction of the teller, but so someone can laugh while they’re drunkenly taking a squatting piss.

Victoria E Pullen: ‘“Victoria” to “Verlaine”’, UAL Graduate Showcase, Chelsea College of Art, 2020 // Photo by Victoria E Pullen

ES: One of the questions that you pose in ‘“Victoria” to “Verlaine”’ is: “Is there integrity in alternative nightlife if it is still institutionally organised?” What are your own thoughts on this? How does this reflect on the art and creative sites integral to these institutionally organised spaces?

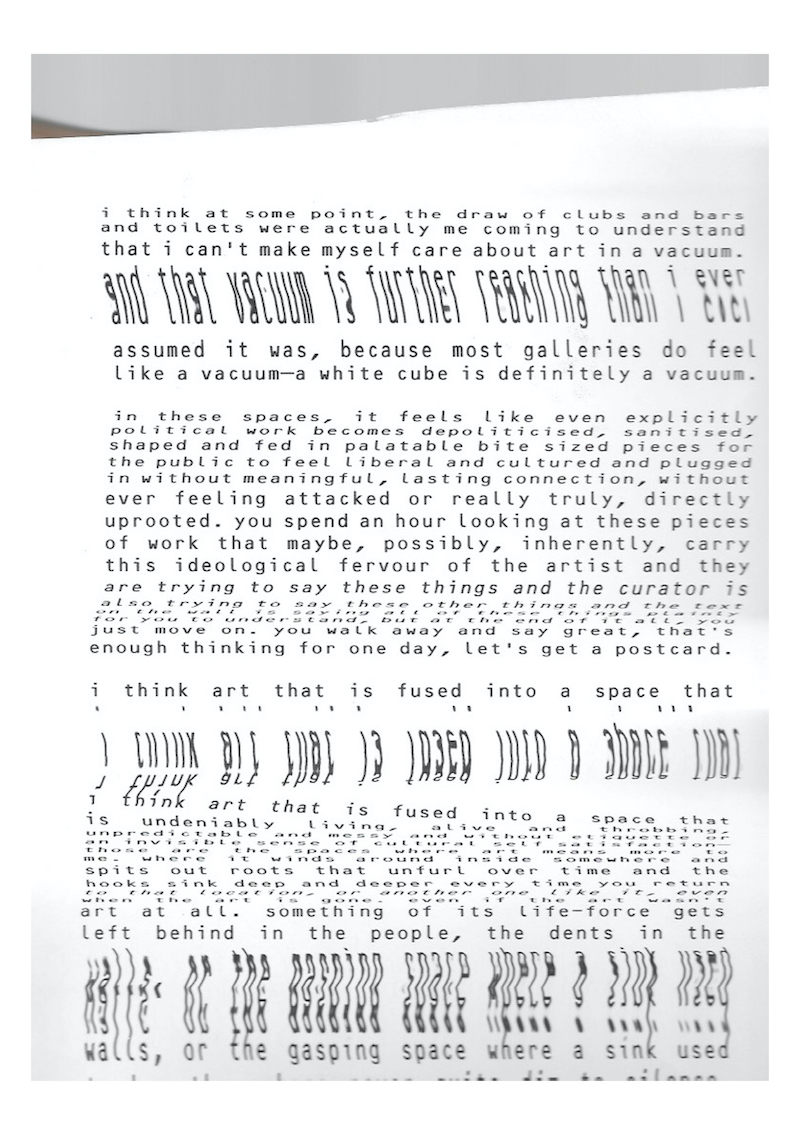

VEP: There’s a page in ‘“Victoria” to “Verlaine”’ where I touch on the transient sterility of white cube galleries, and how art is observed but never fully experienced in that setting. I don’t expect everybody to agree with that and I don’t think traditional galleries are bad; I just have more lasting and impactful interactions with art when there’s more going on. There’s something special about reacting to art in a club setting, when there are no pretensions or inhibitions or egos, just an overspill of genuine feeling. But that’s possible because the art is outside of the institution and the baggage that comes with it. So, by placing the club into the institution, something doesn’t translate the way I’d like it to. It brings back the ego and pretension in the self-conscious way that nightlife should be an escape from.

Under the watchful eye of the gallery, nightlife might be a more pleasant and well intentioned incarnation of corporate nightlife, but that’s still what it is: a farcical and shallow conjuring of what can be found elsewhere, rebranded and polished up. The idea that creatives endorse the idea of a carefully planned, early night of regimented fun feels insincere to me. I don’t think a cramped, sweaty bar that plays guitar music and has half of a functional toilet is inherently better than anything else, but at least you’re not paying £4.50 for a can of Red Stripe and nobody cares if you spill it on their shoes.

ES: What is the role of the persona Verlaine in your work? How does this figure comment on or contribute to the aforementioned discussions and explorations present in your work?

VEP: Verlaine, aka “The Cowboy”, is the tangible result of crafting a conscious identity from resonant fragments of the past. There’s a constant feeling in the work of everything being connected by a thread while remaining disparate and broken: the subcultural past that I never encountered and cannot recover, the lived experience of music scenes I participated in as a teenager, and current modes of nightlife and counterculture. Verlaine is just another piece of the conversation, a way to act out this archive of identities I’ve amassed. I saw a mirror between the mythological incarnation of Wild West outlaws and the mythological narratives that surround subcultures populated by outcasts who remove themselves from mainstream society. “The Cowboy” becomes the psychopomp of the work because it is the self-assured, limitless, heroic figure of that very same existential journey.

I also used Verlaine to reject the heralded white, straight, individualistic masculinity that the American cowboy has come to represent. It carries a deliberate mythology of its own that I’ve decided to rework, just like films and television has whitewashed the racial diversity of the Western Frontier. When I insert myself into that mythology as a queer Black woman, I get to fetishise it the same way mainstream culture fetishises female queerness and ambiguous racial exoticism. In this sense I am following in the footsteps of LGBTQI culture, which has long appropriated cowboy imagery and redefined an icon of American heterosexuality. It also creates this awkward, almost comical contradiction to these musings on British nightlife and music fandom, and that displacement is significant because it is exactly how I’ve felt so much of the time: disjointed, lost, off-kilter.

Verlaine is a fantasised projection looking back onto and into the self, essentially the symbiotic key to fitting together these seemingly unrelated pieces, that ultimately provide a cohesive and meaningful sense of being. I didn’t expect to feel different when I dressed up and took the self portraits, but something wild really did come over me, like the spirit of Verlaine had finally been invoked.

Artist Info

Victoria E Pullen: ‘“Victoria” to “Verlaine”’, UAL Graduate Showcase, Chelsea College of Art, 2020 // Photo by Victoria E Pullen