Article by Juan José Santos Mateo // Aug. 25, 2020

Daniela Ortiz is a Peruvian-born artist, committed to an anti-racist and anti-colonial discourse in her practice. She currently lives in Spain, a country whose passport’s front page includes an illustration of the ships that Columbus sailed toward the so-called “Discovery of America”. In one work from 2014, ‘Réplica’, Ortiz knelt in front of Spaniards celebrating the 522nd anniversary of the “discovery” of America. The action reproduced the gesture of a kneeling indigenous man in front of Spanish friar Bernardo Boyl, immortalized in dozens of monuments: a sting for a country that, for Ortiz, is as racist as European migration policies.

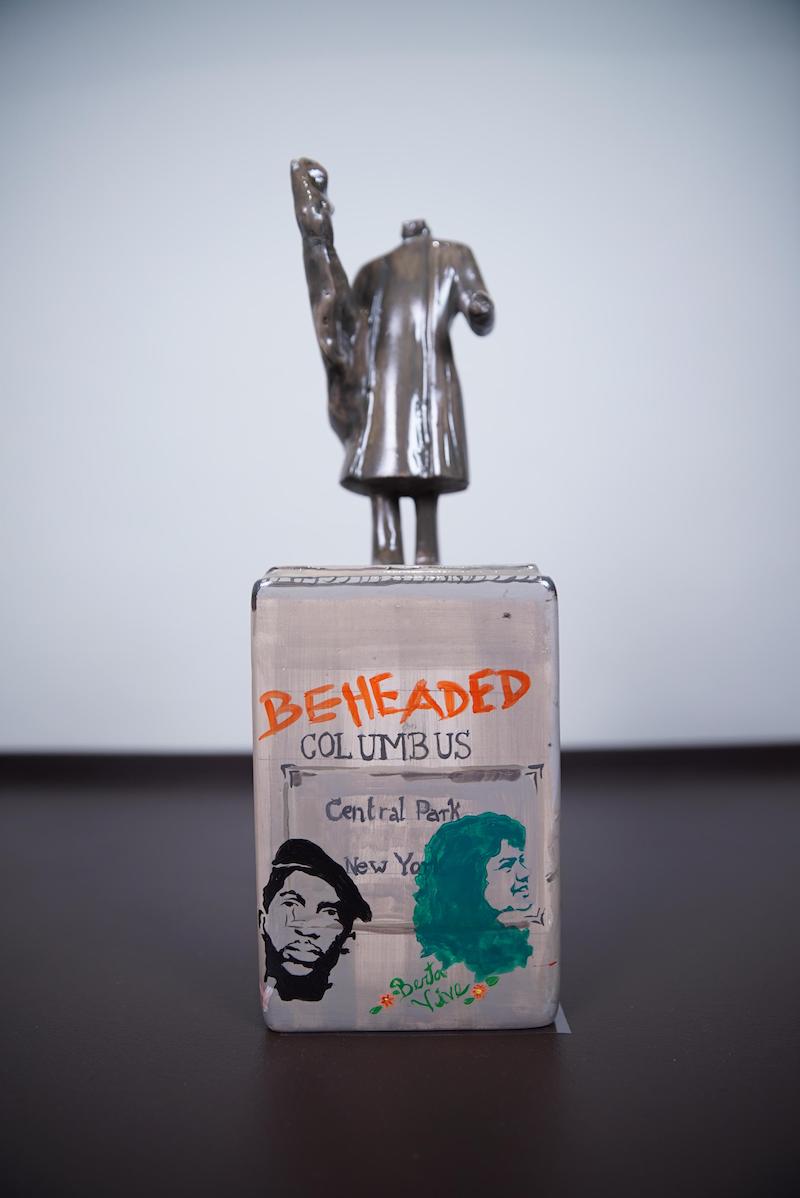

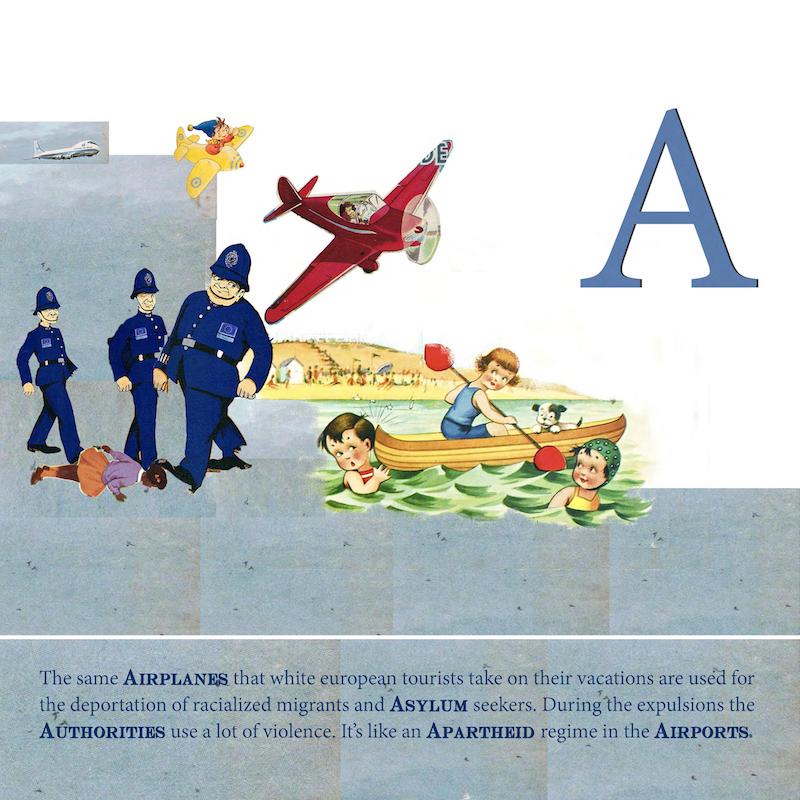

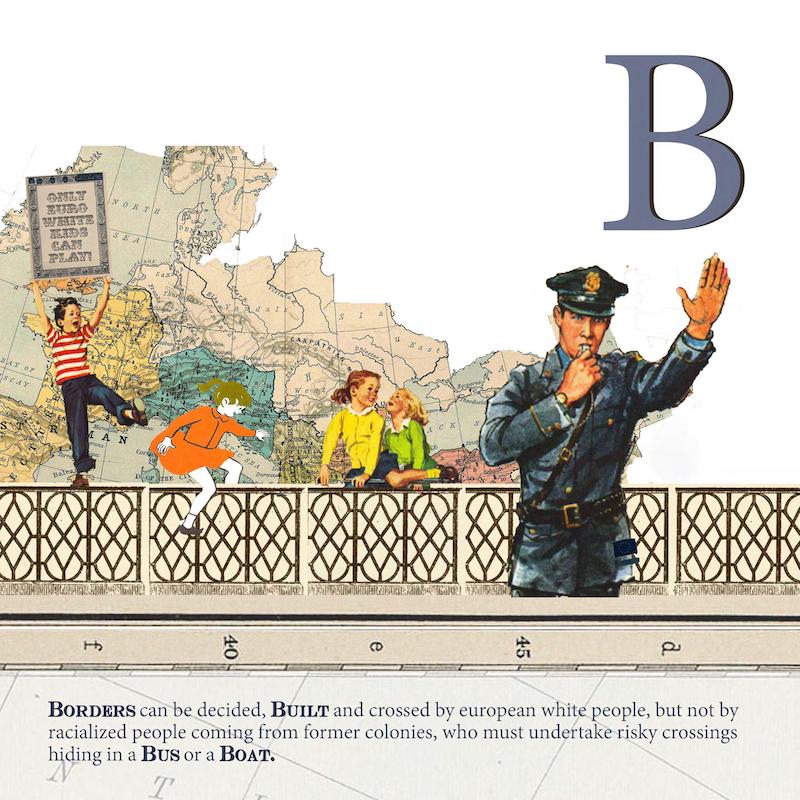

The recent debate around the tearing down of statues, like those of Christopher Columbus, is cause for joy for this creator. We spoke to her about some of her works that relate directly to this political moment, such as ‘El ABC de la Europa racista’ (The ABCs of Racist Europe) (2017), a book created to educate children and help them in pointing out and denouncing racist actions, or her ‘Monumentos anti-coloniales’ (Anti-Colonial Monuments) (2018), a set of hand-painted ceramic figurines that are suggestions to replace five Columbus monuments located in the cities of New York, Los Angeles, Lima, Madrid and Barcelona.

Daniela Ortiz: ‘Monumentos anticoloniales’, 2018 // Courtesy of àngels barcelona Gallery

Juan José Santos Mateo: What’s your reaction to the destruction of statues, taking place in the last few months? Specifically, those of Christopher Columbus? In your 2018 work ‘Anti-Colonial Monuments’, you already proposed replacing statues of Columbus with six anti-colonial monuments, and in another 2014 action, ‘Réplica’, you knelt in front of protesters during the National Holiday of Spain.

Daniela Ortiz: On the one hand, I believe that the demolition of colonial monuments is part of a genealogy that has been going on for many, many years. For example, in 1992, on October 12th in Chiapas, Mexico, the Monument of the Spanish captain Diego de Mazariegos collapsed two years before the Zapatista uprising. In 2004, in Caracas, the Columbus monument also was also torn down in an anti-racist and anti-colonial act. The current moment is part of a historical genealogy in which these monuments have been criticized, attacked and collapsed.

On the other hand, it seems very important to me to bear in mind that in the North American context not only have monuments collapsed, but police stations have been set on fire, the streets have been taken over, the racist prison system and deportation processes have been denounced and the abolition of prisons is being addressed. So we are talking about something that is happening not only because of the symbolic issue, but also because of all the mechanisms of institutional racism that can exist precisely because monuments, street names, etc., are tools that reinforce those racist and colonial narratives that enable a system of immigration control, and that allow an absolutely racist penitential system.

I was very happy to see that there were monuments that had been decapitated, like those ceramics of mine that you mention. I think that my work is not a unique thought, it’s not as if it occurred to me on my own, inspired at home; instead my works respond to collective political processes in which, for many years, as I explained at the beginning, there has been a genealogy of the collapse of monuments as an anti-colonial action in uprising processes, like the one that is taking place now.

JJSM: Do you think the ideal scenario would be to destroy or replace them?

DO: I think—and it is not an individual thought—that the community that is currently destroying those monuments is making it clear: that these monuments must be removed; but not only torn down, they must be painted, debased. Those symbols must be drastically debased: they must be tied, hung and destroyed. It’s not simply—as it has happened in other contexts—that the city council removes the monument, with respect and following protocol, so that they can keep it in a museum or warehouse to see if, in five or ten years, this wave of protests passes and it’s restored. This has happened on different occasions, such as with the Columbus monument in Buenos Aires, which was withdrawn and replaced by one of Juana Azurduy, but then, when the right wing won back the government, they put the Columbus monument back in public space. The act of tearing down a monument is an act that also builds history. When the monuments to Leopold II in Belgium were attacked, history was being created, a symbolic moment was being created that reveals the power of those colonial symbols.

Daniela Ortiz: ‘Monumentos anticoloniales’, 2018 // Courtesy of àngels barcelona Gallery

JJSM: Something you have denounced in many of your works is the prevailing racism in Europe. You have even wanted to convey this to children, with your 2017 ‘ABC of Racist Europe’. To what extent do you think racism affects the lives of immigrants living in Europe?

DO: Today’s Europe has been built thanks to a system called racial capitalism: all this colonial order of plunder, exploitation and enslavement of racialized peoples has built the current European welfare state. To be able to sustain a system of plunder and violence against other territories and against other peoples, and to be able to impose this ideology on the rest of the planet, you need to reproduce racism in each of the spaces of daily life, and of political and public life, because the population has to be convinced in order to coexist with 50,000 dead and disappeared, as it happens on the European borders. To have a system of migratory control, of persecution, detention and deportation of migrants you need to reproduce racism in every space, in the media, in school books, in colonial monuments, in the political class, in the laws, in absolutely all areas of life: this colonial ideology must thoroughly penetrate everything, so that people do not rebel against the violence they are exercising. Rather, on the contrary, they have to be increasingly convinced that this violence is correct.

In the ‘ABCs of Racist Europe’, it was very important for me to create a glossary, to re-analyze many of the terms. On the one hand, it seemed important for me to generate this situation of analysis and, on the other hand, it also seemed very important to enter into children’s literature, which is another of the great fields that reproduces this racism, using super innocent language. Books, for example, that tell you that when Columbus arrived in America it was a meeting of two worlds: they sweeten a situation of violence. They do not tell children that the colonial process was a process of plunder and death. It was not a process of multiculturalism, nor of friendship. Those narratives normalize the colonial system, to the point that when you question figures like Columbus, many people reply: “we did you a favor, you were in loincloths, and we brought you culture, we brought you the language”. Because through children’s books, university studies and the media, they have constructed this entire story that is absolutely false.

Daniela Ortiz: ‘The ABCs of Racist Europe’, 2017 // Courtesy of àngels barcelona Gallery

JJSM: You have worked inside and outside European institutions. Do you feel that your work has been tamed inside Spanish museums or galleries? Do you think this has diminished the power of your message?

DO: I always separate what it is to make art from what it is to do exhibitions. Because, as you say, the museum is a machinery of domestication. I am more interested in seeing how people relate to my work outside the institutional space.

Daniela Ortiz: ‘Monumentos anticoloniales’, 2018 // Courtesy of àngels barcelona Gallery

JJSM: Many believe that the idea of “racial superiority” is something from the past, or that it occurs in other countries. What is your stance?

DO: White supremacy has infinite strategies to allow racism to renew itself. One strategy is, as you say, to place it in the past. Another one that the white left uses a lot in Spain, is to say that racism only exists in the United States or in Latin America. Another is to link racism to a far-right minority group, or to the lower class, to hide that it is precisely the middle class that supports the machinery of institutional racism.