by Dagmara Genda // Oct. 2, 2020

It’s not without the slightest hint of irony that precisely those men who have abused their power tend to liken their reckoning to a witch hunt. The most notable example is Donald Trump, who, in reference to the impeachment trials of 2019, scream-tweeted “WITCH HUNT!” from his favorite social media pulpit. In a 2017 interview with the BBC, Woody Allen, of all people, described the allegations against Harvey Weinstein as potentially fostering a “witch hunt atmosphere.” Privilege and power, in a bizarrely clumsy yet too-often-accepted sleight of hand, most often allow the perpetrator to take on the role of the victim. When the need arises, these men fan the flames of moral outrage and hysteria of their own kith and kin—united under the figure of the white male—in order to denounce as “abnormal” or “irrational” the people who do not fit into their “rigid role models and structures.”

Gluklya (Natalia Pershina-Yakimnskaya): ‘Monument for Modern Slavery,’ 2020 // Courtesy of Kulturamt Spandau

The terms “abnormal” and “irrational,” note curators Alba D’Urbano and Olga Vostretsova in their exhibition text for ‘disturbance: witch,’ are part of the arsenal of “a new witch hunt,” in which feminists and queer people are labelled as deviant and unwanted. However, they also imply that these terms can form the basis for solidarity. A spiritual kinship to the witch can be traced back to the 1970s, when feminists appropriated the pejorative label by elevating the witch to a feminist archetype. Since then, the witch has become a productive symbol for those struggling under the yoke of so-called normality and reason. If the maligned deviant is in fact the persecuted hero, then the normal is cast in a garish light, as the remainder of an outdated, colonial power.

It is no coincidence that the Spandau Citadel was chosen as a home for this exhibition. In the 16th and 17th centuries, the Citadel’s Juliusturm served as a prison for women who had “fallen from grace” or were outright accused of being “witches.” According to the Encyclopedia Britannica, three-quarters of all European witch hunts occurred in Germany and the highest number of witches—mostly women but also men—were executed here. Reminders of this murderous past can be seen before even entering the show. Outside the Citadel’s barracks artist Gluklya (Natalia Pershina-Yakimnskaya) has hammered T-shaped wooden stakes into the ground as part of her ‘Monument for Modern Slavery’ (2020). Clothes, some of which are made for children, have been stretched over the wood as a means of connecting today’s global clothing market to historical systems of forced labour. The objects also prompt associations with loss and homelessness, evoking images of the refugees whose makeshift camps recently burnt to the ground on the Island of Lesbos. Like the historical witch, these people are deemed a threat to the status quo. Cynically, even hysterically, traumatized families fleeing war are often vilified as “invaders.”

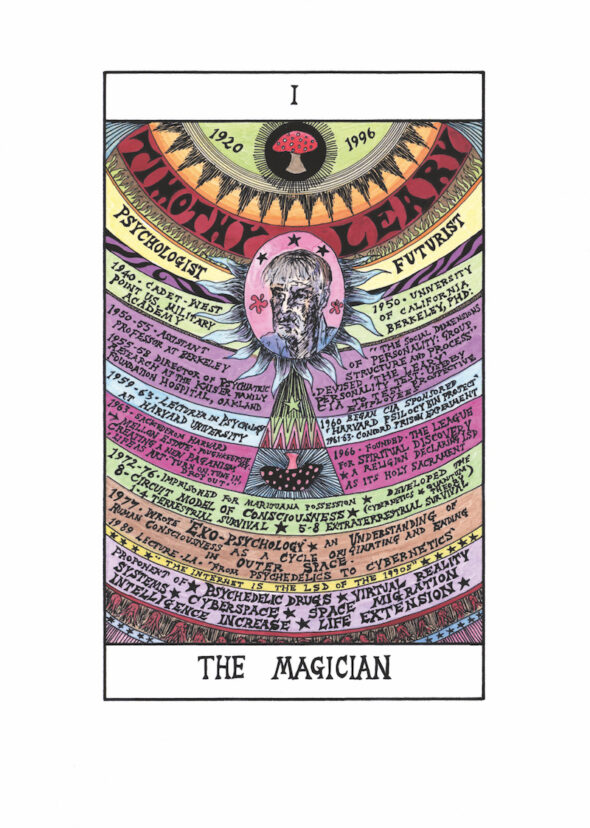

Suzanne Treister: ‘HEXEN 2.0 / Tarot,’ 2009–2011, Deck of 78 Tarot cards, je/each 15 x 9,5 cm // Courtesy: Annely Juda Fine Art London; P.P.O.W. New York

Quoted in a 2018 opinion piece in Frieze, ‘The Return of the Witch in Contemporary Culture,’ artist-academic Hestia Peppe explains: “Witches’ magic is the wisdom and practice of oppressed peoples; the occult is the organized keeping of secrets by those in power…It is naïve to simplify the politics of magic and overlook its use by fascists and white supremacists.” Magical thinking and its connection to power is exactly what Suzanne Treister traces in ‘Hexen 2.0 / Tarot’ (2009–2011). Within large historical diagrams-cum-ritualistic-markings, Treister has drawn a web of references linking the history of the internet with the military, cybernetics and the Macy Conferences held in New York (1946–1953), which were hosted with the goal of designing a science of the workings of the human mind. She pictures the modern progress of technology as less of a path to enlightenment than a murky network of occult control. Her Tarot deck, displayed in its entirety under a vitrine, features Aldous Huxley as The Fool and Timothy Leary as The Magician. Her card for The World draws a chilling visual connection—“WWI, WWII, WWW”—implying that we might be deep within the third largest conflict of human history without even noticing it.

Emily Hunt: ‘The Earth is a Witch and the Men Still Burn Her,’ 2020 // Courtesy of Kulturamt Spandau

Johanna Braun also makes historical diagrams of sorts, though her process lies somewhere between Aby Warburg’s ‘Mnemosyne’ and the paranoid circling of a conspiracy theorist. ‘Wayward Reproductions (On Mass Hysteria IV)’ (2020) is the latest of several wall-sized photo-collages that trace the affective journey of the term “witch” in our cultural imaginary. Weaving through the wallpapered chaos of film posters, articles and historical prints, Braun has smeared, in dripping horror-film red, sayings and quotes related to witches. In this version young “witch” Greta Thunberg can be seen in the top left corner ringed by Trump’s habitual frothing. “Chill Greta, Chill!” sneers the President of the United States in the tone of a middle school bully.

Perhaps more important than the show’s cartography of injustice is the unstated proposal that witchery—or abnormality—might be an inclusive kinship structure for those left out of the system or for those not wanting to take part. This can be inferred from the diversity of artists on show. Rather than working within established polarities, the curators have included men and women, as well as established and emerging artists. Works from the 70s, like Libera Mazzoleni’s drawn and collected images depicting her feelings of “kinship” with Ulrike Meinhof, share a space with artists that are still fresh names in Europe, like Australian artist Emily Hunt or Uruguayan Emilio Bianchic. Hunt’s detailed wall drawings, ‘The Earth is a Witch and the Men Still Burn Her’ (2020) read like apotropaic marks to ward off evil, while Bianchic’s photo, ‘Uh La Lá LA la lA’ (2016), of a prodigiously hirsute human appendage squeezed into a high heel, might document the result of a witch’s curse. Another witchy man is Darmstadt artist Horst Haack who, since 2009, has devoted much if his time to the depiction of fantastical creatures. ‘Tierleben’ is presented as a curiosity cabinet that documents freaks, mutants and mysterious creatures we may not have yet discovered. To be a witch, it seems, need not be an unfortunate fate, but a choice and a means of resistance.

Emilio Bianchic: ‘Uh La Lá LA La lA,’ 2016, digital print, 120×70 cm // Courtesy of the artist

Indeed diverse practices of resistance, whether they be activist, poetic or academic, run like a thread throughout the exhibition. This unity is unwittingly emphasized by the soundtrack of Veronika Eberhart’s single-channel video ‘9 is 1 and 10 is none’ (2017). The melancholic music bleeds beyond her piece into the entire exhibition, creating an auditory stage for the show. Eberhart’s video features three futuristically-dressed witches of various sexes, performing in an old woodworking shop on the border of Austria and Slovenia. Their choreography is based on Hans Baldung Grien’s ‘Neujahrsgruß mit drei Hexen’ (1514). His dynamic, raunchy composition lends itself to interpretation through movement. The witches’ mysterious dance breathes life into the silent shop and infuses obsolete machines with new, even deviant, possibility.

The online manifesto of participating artist Gluklya reads: “The place of the artist is on the side of the weak,” an expression of kinship shared by everyone in the show. The artists engage dominant narratives from the perspective of the persecuted, the affected and the forgotten not only to expose the interests served in official histories, but to point towards pathways of future possibility. Solidarity, they imply, cannot be founded on traditional models of kinship and familiarity; it is first and foremost a willingness to embrace the unknown.

This article is part of our monthly topic of ‘Kinship.’ To read more from this topic, click here.

Exhibition Info

Citadel Spandau

Group Show: ‘disturbance: witch’

Exhibition: Sept. 11–Dec. 27, 2020

museumsportal-berlin.de

Am Juliusturm 64, 13599 Berlin, click here for map