by Cristina Ramos // Oct. 16, 2020

There are many lessons that we can learn from the vegetal world, such as how to live together in a non-intrusive way (in the same way that leaves position themselves relative to their neighbours), adaptability to dynamic environments and sensorial communication through widespread networks. The work of artist and filmmaker Barbara Marcel reflects on discourses surrounding colonial imagery and its connection to our perception of nature. Her work engages with a discussion on the commodification and exploitation of natural spaces like the Amazon, and how these practices are rooted in colonial thinking, at the same time that it documents the current work of scientists in building up plant-knowledge.

By reflecting upon an overall ecological principle of connectivity, Marcel invites us to wonder how we can shape the future through living in close connection with plants and trees and what kind of symbiotic relations can emerge through this coexistence. We talked about some of her recent projects, building commons across science and art in response to environmental concerns and the urgency of recognizing kinship with chlorophyll beings.

Barbara Marcel: ‘The Open Forest,’ 2017. HD essayfilm, colour, sound, 21min17s. Video still // Courtesy of the artist

Cristina Ramos: Thinking about the fact that the vegetal world helps us to maintain our breath by producing a high percentage of the oxygen in the Earth could teach us to perceive that being alive requires both dependency and attachment to our natural upbringing. Every time I find myself walking in a forest, I feel invited to pay attention to my heart beat, to keep silent and to cultivate it not as a lack but as a place where we can free ourselves from the weaving of discourses and habits in which we are involved daily. This thought was prompted by one line from the script of one of your filmworks, ‘The Open Forest’, when it is said: “Isn’t the gesture of planting also a gesture of waiting?”. How could we empathize with our socio-economical need to decelerate through thinking like a forest?

Barbara Marcel: The phrase is a quote from the essay ‘The Gesture of Planting’ by Vilém Flusser, turned into an open-ended question. Besides having written many important texts about the so-called “technical images”, Flusser was a great thinker in-between worlds, who influenced my border thinking between Brazil and Germany. ‘The Open Forest’ is a work about the relationship between images and words, between what is said and what is seen. It is a first attempt to learn how to listen and relate to the vibrant matter that runs alongside and even inside of us, trying to focus my intelligence on other parts of the body than just the visual memory about the forest.

There is a long tradition in western culture of thinking of the forest as a space of cultural emptiness and silence propitious for social isolation and, therefore, an occasion for the practice of cultural techniques of solitude. Not that this is a bad thing, there are many sorts of forests around the planet and they can be thought of in many ways, but the silence of most European forests is worrying because it is directly linked to deforestation. This is why Flusser talks about the gesture of planting as a potentially violent gesture connected to colonization. What I have learned and try to communicate with the film is that not all peoples have established this same relationship of devastation with their surroundings. If the gesture of planting can be considered a gesture that initiates the notion of property, the Amazon must be understood as a large garden cultivated by the various indigenous peoples, and more recently caboclos and quilombolas who live in communion with the forest and all non-human beings. Also with them, we have a lot to learn.

Barbara Marcel: ‘The Open Forest,’ 2017. HD essayfilm, colour, sound, 21min17s, Video still // Courtesy of the artist

Barbara Marcel: ‘Ciné-Cipó (Cine Liana)’ at ATTO Amazon Tall Tower Observatory, 2020. HD 4-Channel video installation, colour, sound, aprox. 120min, Video still // Courtesy of the artist

CR: Ecology is considered as the influence that the environment exerts on behaviours and mentalities of individuals immersed in it. I wonder if we can reconsider this notion further and think of the vegetal environment as a subject rather than an object in order to create a new production of values, a mutation of human identity. If so, we might be able to build kinship with plants and trees that goes beyond a mere use-value, and to realize that we can be influenced by them. During the making of ‘The Open Forest’ you were in dialogue with scientists researching the Amazon forest, as well as with a group of Brazilian and foreign artists. Did you come across any particular interaction or approach where a symbiosis between humans and the vegetal world was taking place?

BM: Something that I find important to stress is the need to question dualisms such as subject/object, nature/culture, civilized/primitive. These dichotomies organize the domination system of modern/colonial western thinking and have a history that, only in the last few years, we have begun to deconstruct with decolonial, ecofeminist and new materialism studies. The more unstable they become, the less governed they are under the principle of domination. I met ecologist Charles R. Clement, during a residency in the Amazon, who told us an anecdote that I find quite revealing about interspecies relationships. Corn was growing in Mexico as a kind of grass until humans started selecting the bigger and more appetizing grains, to then choose the best seeds for planting, thus contributing to a certain evolution of the plant at the service of our nourishment. Who benefited most from this?

According to Charles, if we measure it in quantitative terms, it is the corn that wins. There is much more corn on the planet today than human beings. Unfortunately, in the Americas we have lost the diversity of colors and flavors selected for centuries by small-scale farmers’ ancestors because of a standardized diet made by the agribusiness of the capitalist monoculture system. If we admit the effects that these kinds of beings and materialities can have on human beings, it would be better to think of them as actants—as Bruno Latour says—and recognize that they have a vitality of their own and, in many cases, end up determining the courses of life on the planet as much as us. Perhaps a way to produce kinship with plants would be the cultivation of a more sensorial attention to the non-human forces operating inside and outside our body.

Barbara Marcel: ‘Ciné-Cipó (Cine Liana)’ at ATTO Amazon Tall Tower Observatory, 2020. HD 4-Channel video installation, colour, sound, aprox. 120min, Video still // Courtesy of the artist

CR: More than ever, it seems urgent to work within a common ground of solidarity between the fields of contemporary art and science. Working with materials that come from biology and environmental science, art can bring a humanist sense to scientific research and raise awareness of environmental issues in a more efficient way. As you said, to cultivate a more sensorial understanding of what is at stake. In your most recent work with the video installation ‘Ciné-Cipó (Cine Liana)’ you propose a meeting between two local Amazonian activists and scientists from the ATTO tower for climate observation, through the temporary transformation of the tower into a community radio station. Learning with plants seems a very relevant process in this work.

Barbara Marcel: ‘Ciné-Cipó (Cine Liana)’ at ATTO Amazon Tall Tower Observatory, 2020. HD 4-Channel video installation, colour, sound, aprox. 120min, Video still // Courtesy of the artist

BM: The Amazon Tall Tower Observatory (ATTO) is an international scientific project studying the complex interactions between the forest, soils and the atmosphere in order to understand the role of the Amazon basin within the Earth system. As it is an international cooperation between Brazil and Germany, the project seemed to me a perfect meeting point for a project and the creation of alliances between various forms of knowledge in defence of the forest. Only an art project would be able to convince all the institutions involved to carry out this transformation, even if temporary, of the tower into a community radio.

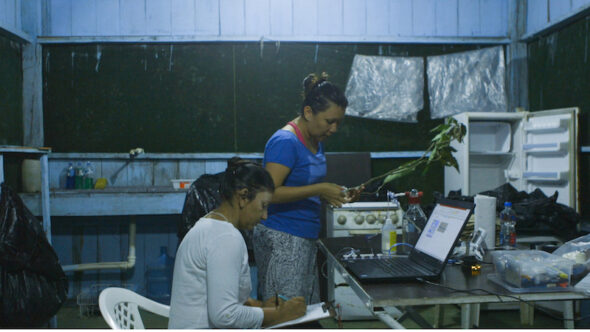

‘Ciné-Cipó’ is a project about communication between different worlds, about the encounter and dialogue among people who live in different time-spaces. The intention was to create a portrait of the complexity of issues and discourses around the most biodiverse forest on the planet. The project title is inspired by the liana plant, which grows horizontally through the forest connecting and transporting species. Some species of liana are used as medicinal herbs in the Amazon, others support the architecture of houses. ‘Ciné-Cipó’ is a term that I have been thinking as a way to translate my artistic practice of assembling images and words, thoughts not about the forest and its inhabitants, but with them. One of the scientific teams that marked me most along the observational process of the project were scientists Lorena Rincón and Aurélia Ferreira, who were collecting treetop branches for studies of resilience of trees facing drought. The whole process of collecting branches to the measurements of the vulnerability rates of the plants in a very improvised laboratory in the field, seemed to me very seductive, very alive, different from my expectations about what would be a scientific field research. One of the things I learned from the project was that making science can also be full of enchantment.

This article is part of our monthly topic of ‘Kinship.’ To read more from this topic, click here.

Artist Info

Exhibition Info

ZKM | Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe

Group Show: ‘Critical Zones: Observatories for Earthly Politics’

Exhibition: July 24, 2020–Feb. 28, 2021

critical-zones.zkm.de

Lorenzstraße 19, 76135 Karlsruhe, click here for map