by Noëlle BuAbbud // Nov. 5, 2020

Walking through ‘Living the City’ is at times as overwhelming as moving through an unfamiliar metropolis. Held in the main hall of the former Berlin-Tempelhof airport building, a site of contentious history and closed off to public access until now, this exhibition collages together a complex process of city life and civic action, always in flux. The format is akin to a scaled-down World’s Fair of sorts, where smaller exhibitions and booths are divided between subcategories of action, such as participating, learning and playing, and videos, photographs, illustrations, sound installations, sculptures and literature populate the built environment. But instead of celebrating the achievements of nations, ‘Living the City’ brings together fifty stories of cooperative architectural, artistic and urban-focused projects, each concerned with various aspects of urban ecologies. This exhibition comes at a crucial moment, when the pluralistic nature of cities around the world is under constant pressure and threat of erasure.

‘Living the City’ exhibition view, 2020 // Copyright Schnepp Renou

The sculpture ‘Pleasure Places of All Kinds’ by Ahmet Öğüt can be seen as a harbinger of what happens when governments and corporate interests take control of urban policy. These models of ‘Nail Houses’ stand alone, with the earth around them dug out: the last houses standing in the Fikirtepe Quarter of Istanbul. The tenuous reason given for mass demolition was earthquake safety policy, however, these questionable regulations speed up an urban transformation process, displacing residents from their neighborhoods in order for developers and real estate companies to come in and turn a profit. These homes stand in defiance, even as they are surrounded by excavated and barren land.

Ahmet Ögüt: ‘Pleasure Places Of All Kinds: Fikirtepe’, 2014, sculpture, 150×150×70 cm // © Private Collection, Amsterdam

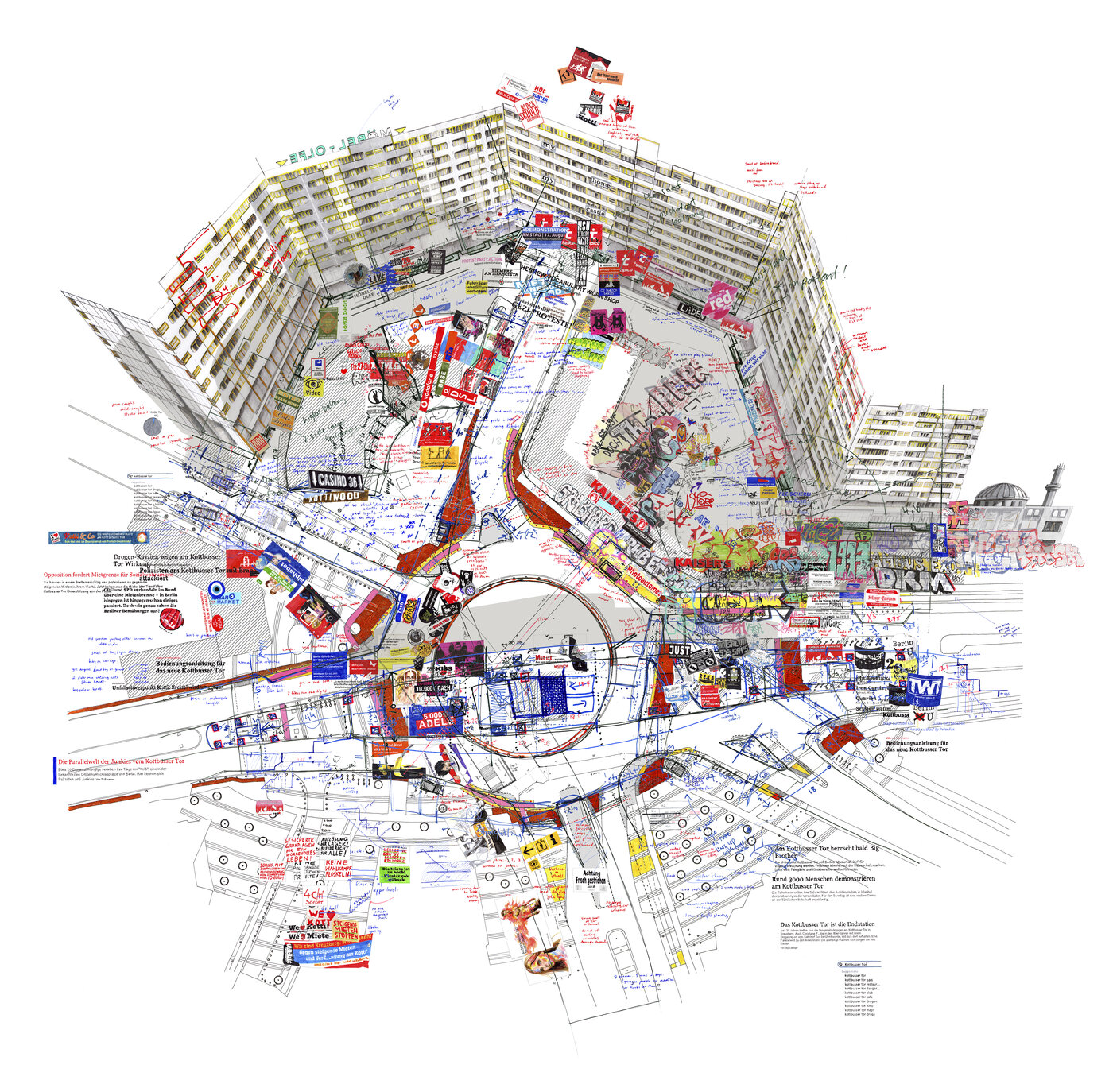

Larissa Fassler’s ‘Kotti (revisited)’ maps the psychogeography of Kotbusser Damm, compiling notes, movement, graffiti and headlines. These inscriptions are as much a part of the history as the architecture. The group Crimson Historians and Urbanists illustrates a panoramic map dealing with cities—such as Los Angeles, London, Cairo and Hong Kong—and the role of street protests in their project ‘Do You Hear the People Sing?’. These maps act as a chronicle of struggle and protest, the streets being an accessible space where inhabitants of a city can join together and express their discontent with state policy.

Larissa Fassler: ‘Kotti (revisited)’, 2014, Fine Art Print, 157×160 cm // Courtesy of Larissa Fassler

‘A Model City of Memories and Dreams: World City’ is an assemblage of model structures built by people who have left their homes to seek refuge. ‘World City’—created by Berlin-based association Schlesische27 and several other organizations—is one of the most striking pieces in the exhibition. Children, teenagers and adults built each part of the structure based on memory or a future idea of place. Taken together, this cooperatively imagined site offers a vision of a pluralistic city where there are no borders or barriers to life.

The landscape of the cosmopolitan city develops from around 150 houses that were built by refugees together with the Berlin association Schlesische 27 and other organizations // © Aris Kress

‘Living the City’ offers a range of collective projects that, presented alongside one another, offer insight into effective civic action and opportunities to design environments that embrace societal engagement. When decisions are left to real-estate investors, developers and certain political bodies, their profit-driven interests destroy the ecology of cities—they become prohibitive and alienating spaces devoid of vibrant social interaction and polyphonic histories. This three-month-long exhibition has been commissioned by the Federal Ministry of the Interior, Building and Community within the framework of the National Urban Development Policy. It is important to ask, then, what are the interests of this ruling body and what are their policies? Is ‘Living the City’ also a performative gesture?

Crimson Historians and Urbanists: ‘Do You Hear the People Sing’, since 2015 // © Crimson Historians & Urbanists

It would be irresponsible to ignore that, parallel to this exhibition, there is a tense climate in Berlin, where affordable housing is nearly impossible to find, people are being evicted from their homes, neighborhoods are undergoing rapid gentrification, mobility is impeded and migrant populations are facing increased police brutality. Still yet, the city of Berlin (and the same funding body of this exhibition) has invested millions of Euros into the reconstruction of the Berlin Palace and Humboldt Forum, a contested site of colonialist ideology, reinscribing oppression. What are the priorities of this commissioning body?

As an exhibition, ‘Living the City’ has the potential to inspire people to take matters into collective hands, by exposing the intricacies of policy and money flow in the crucial decisions that affect our cities. Set in a building with fascist architectural origins, whose hangars have more recently been used to house refugee populations in the city, ‘Living the City’ prompts countless questions about the ways in which art and exhibitions in temporary use spaces, even with the best intentions, can pave the way for further gentrification. What comes into sharper focus, standing in the main terminal of Tempelhof airport, is that designs for its future are already laid out through the gesture of placing an exhibition in the space, and here it is important to continuously refuse to become a complacent public.

With the recent closure of exhibition spaces across the city, ‘Living the City’ is now offered in the form of a “virtual city collage” on the exhibition’s website, inviting visitors to connect with more than 50 urban stories, sorted and overlapped in eight thematic areas.

Exhibition Info

Flughafen Tempelhof

‘Living the City’

Exhibition: Sept. 25–Dec. 20, 2020

Online exhibition: livingthecity.eu/virtuelle-ausstellung

livingthecity.eu

Platz der Luftbrücke 5, 12101 Berlin, click here for map