by Emily McDermott // Nov. 10, 2020

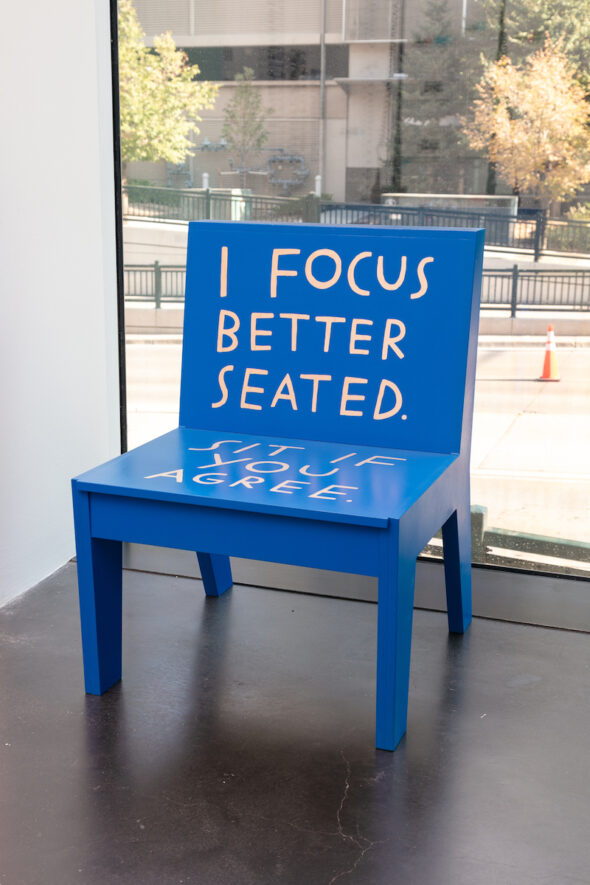

Benches placed in galleries, emblazoned with the message “This exhibition has asked me to stand for too long. Sit if you agree,” or cushions on chairs in a museum that read “There aren’t enough places to sit around here. Sit if you agree,” are sights for sore eyes—not to mention sore or disabled bodies. With their project ‘Do you want us here or not’ (2018–ongoing), the New York–based artist Shannon Finnegan inserts these interventions into exhibition spaces. The works reflect their overarching practice and its focus on advocating for accessibility in both physical and digital spaces.

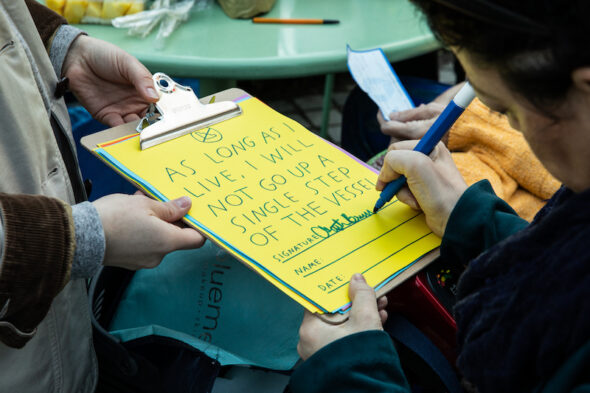

This impetus comes through in their series ‘Anti-Stairs Club Lounges’ (2017–ongoing), which creates exclusive spaces for visitors who cannot or choose not to go up stairs. When invited to show work in the Hudson Valley, New York, at the Wassaic Project’s exhibition space Maxon Mills—a building with seven floors but no ramps or elevator beyond the ground floor—Finnegan decided to create a lounge replete with comfortable furniture, custom textiles, books, phone chargers, snacks, refreshments and more. The catch: visitors could only enter upon signing an agreement, in which they promised not to go up a single stair, thereby foregoing a visit to the upper floors where the majority of the exhibition was on view. Finnegan held an action with similar intentions when the Vessel, a structure comprising 154 interconnected stairways, was unveiled in New York City’s Hudson Yards development.

Shannon Finnegan: ‘Anti-Stairs Club Lounge,’ 2017–18, Wassaic Project, Wassaic, NY // Photo by Verónica González Mayoral

Image description: An orange wall with big text in a stair-inspired font that says, “Anti-Stairs Club Lounge.”

Shannon Finnegan: ‘Anti-Stairs Club Lounge,’ 2017–18, Wassaic Project, Wassaic, NY // Photo by Verónica González Mayoral

Image description: The interior of the lounge featuring chairs, reading materials, lamps, fake plants, candy, and a mini-fridge.

Most recently, the artist began addressing accessibility in digital space through a series of creative workshops about alt-text (text entered into the backend of websites or on social media platforms to enable screen-readers to access visually-driven content) created in collaboration with artist, activist and scholar Bojana Coklyat. To a disabled audience, some of Finnegan’s subject matter might seem like old news, but they see their work as a building block within a much larger ecosystem. Their work, they say, “is interdependent with work by many other disabled artists and thinkers. It is part of a specific network and lineage.” In this interview, Finnegan speaks about this ecosystem, their disability-centering practice and how artists and institutions can—and should—change the ways they think about accessibility.

Emily McDermott: In college, as a studio art major, you were doing a lot of printmaking and drawing with subtle references to your experience as a disabled person. At what point did you decide to make work specifically about disability?

Shannon Finnegan: Disability is such a rich site for thinking about many different things, but it’s often not treated that way, especially by non-disabled people. So, in college, I had a lot of fear about being tokenized or having my work read very narrowly, which was a barrier in terms of making work explicitly about disability. But then, five or six years ago, I felt like I wanted to address that part of my experience more directly. A main catalyst for this was looking at mainstream representation of disability and realizing there was so little that resonated with my lived experience. At first, I worked in ways similar to how I’d been working before, with a lot of text-based drawings. But then, as I realized I also wanted to center disabled people as the primary audience for the work, I knew I was going to have to work in different ways. This process happened as I was reevaluating my own access needs and reconsidering the things I had been taught to “ignore” or “power through”—reconsidering, for example, what supports my participation in a space, what makes me feel welcome, what my bodymind needs.

Shannon Finnegan: ‘Do you want us here or not,’ 2020, MCA Denver, Denver, CO. Fabrication by Joshua Bemelen // Photo by Wes Magyar

Image description: A chaise lounge in a patch of sunlight that says, “Here to lounge. Lounge if you agree.”

EM: How do you decide which project to exhibit where? For example, when you’re invited to show at a space, do you visit it and see what it needs?

SF: It’s been a learning process about how to collaborate with spaces. For a show at Tallinn Art Hall, they had a lot of existing seating, so we made the choice to add cushioning and softness to the seating that was already there. On the other hand, right now I’m part of a group show at MCA Denver, where there aren’t a lot of benches, so it made more sense to fabricate new pieces.

It’s important to me that the benches are additive. My benches should not replace any seating that would’ve been planned for the exhibition. They should only be added, and they can then be in conversation with the gallery or museum’s typical seating setup. When I look at benches and seating in galleries, it’s often so minimal. So rarely is there a back on the seating, and it’s often very uninviting. Having the existing seating together with my benches can shed light onto design choices.

EM: I want to go back to what you said about making work specifically for a disabled audience. What led you to making this active choice?

SF: It really comes from my own experience with the work of other disabled artists, writers and thinkers. Growing up, I was isolated from other disabled people. I wasn’t encouraged to seek out disability culture or disabled peers or mentors. So, it was through the work of other disabled artists and writers that I started to understand things that I thought were my own unique experiences are actually shared experiences, and that they are culturally shaped. The desire to center disabled audiences came from this experience: I wanted to be part of the ecosystem that was so nourishing to me. Also, disabled audiences are so rarely centered in museums and gallery spaces, so I wanted to push back against those power dynamics.

EM: How do you hope a non-disabled audience engages with your work?

SF: The binary of disabled/non-disabled is very slippery. The benches are a great example: a lot of people who don’t identify as disabled are excited about seating. There’s a lot of messiness around this binary, but putting that aside, when I’m thinking about a non-disabled audience, my work might provide an experience of being outside and looking in, rather than being centered. I’m always trying to avoid putting myself in situations where I need to teach non-disabled people or do a kind of 101 on disability and access. Whereas when I’m speaking to other disabled people, I’m able to get to the core of what’s on my mind. I think non-disabled viewers also benefit from this, because they’re getting a richer and more nuanced perspective.

Shannon Finnegan: ‘Anti-Stairs Club Lounge at the Vessel,’ 2019, Hudson Yards, New York City, NY // Photo by Maria Baranova

Image description: About 40 people posed in front of the Vessel sporting neon orange, Anti-Stairs Club Lounge beanies and holding Anti-Stairs Club Lounge Signs.

Shannon Finnegan: ‘Anti-Stairs Club Lounge’ at the Vessel, 2019, Hudson Yards, New York City, NY // Photo by Maria Baranova

Image description: A close-up of Christine signing a pledge: “As long as I live, I will not go up a single step of the Vessel.” The pledge on colorful paper, riso-printed with blue hand-drawn text, and has a crossed-out-stairs symbol at the top.

EM: I read an interview where you spoke about something similar. You mentioned how, when you are exhibiting at an institution, you try to find a balance between not feeling like you are giving 101 and absolving them of their responsibility to accessibility, but also to not disengaging from the topics.

SF: My role in accessibility with an institution or organization is something that continues to be really complicated. I’m often in settings where I know if I don’t make, ask and follow-up on the access, it won’t happen. But access work is often, in some ways, outside of the scope of what I was brought there to do or how my time is being compensated. I’m trying to figure out how I can create access but not in ways where the institution is able to step back and be like, “Okay, Shannon’s got it.” But I find it hard to set those boundaries.

EM: What are some strategies you’ve applied in trying to achieve this balance?

SF: Last fall, I was talking with Dustin Gibson and he said he thinks about access planning as part of the work. That’s been a helpful framework: all of the emails I send, all the requests that I put in, all the times I check the alt-text is all part of the work, even if it’s not usually recognized in that way.

EM: Fannie Sosa, an artist in Berlin, compiled ‘A White Institution’s Guide for Welcoming Artists of Color* and their Audiences,’ which provides a framework for institutions so they can learn and take on the necessary work in order to welcome BIPOC artists without asking them to take on additional emotional and physical work. It sounds like something similar could be useful for ableist institutions.

SF: Yeah, I have so many conversations about access with people who want to do everything the same as they usually do it but make it accessible, and that’s just not how it works. The process of thinking about accessibility is and should be fundamentally transformative. It needs to involve the reevaluation of timelines, budgets, ways of working and who is in the space. It’s not just an overlay to existing practices. When I think about what needs to happen for disabled people to exist and thrive, it’s such a long-term project that is also interlinked with dismantling capitalism, white supremacy, settler colonialism and other extremely violent, harmful structures. But then there are also things that feel so doable, like adding benches, yet they’re still not being done. If that was prioritized, it could happen tomorrow. Most museums have seating in storage that’s just not being used.

I’ve actually done some research to find out what the hold-up is around seating. At first, I thought museums didn’t want us to spend time there, that they were trying to move crowds through. But then I was talking to someone in the UK and one of the arts funding measurements is the length of time visitors stay in the museum. If visitors spend more time in the museum, it can lead to increased funding, so there are actually incentives to get people to stay. Then I thought it could be the cost of buying seating. But, from my research, those aren’t the reasons; it’s curatorial and that curators have specific ideas about what an exhibition should look like, including sightlines. The curatorial vision is often the barrier to having more seating.

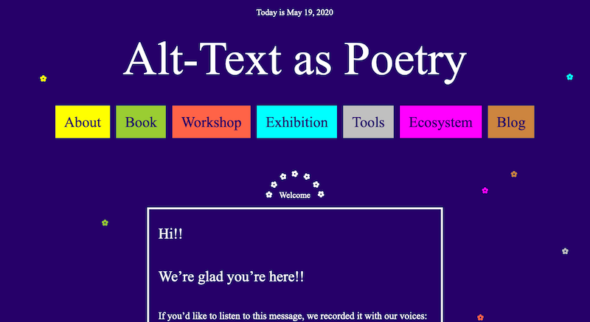

Bojana Coklyat and Shannon Finnegan, Alt-Text as Poetry Website, 2020, Designed in collaboration with Laurel Schwulst and Taichi Aritomo // Courtesy of the artists

Image description: A screenshot of a webpage. The heading reads “Alt-Text as Poetry” with a colorful navigation bar below that include the options: About, Book, Workshop, Exhibition, Tools, Ecosystem, and Blog. Below that is a welcome that says, “Hi!! We’re glad you’re here!!” There are little flowers sprinkled around the page.

EM: Shifting from physical to digital accessibility, I want to ask about your ‘Alt-text as Poetry’ workshops and how they came to be.

SF: When I applied for a residency at Eyebeam, which is a space that supports artists thinking about technology, I was considering how some of the ways I think about access in physical space might be related to access in digital space—pushing back against compliance-oriented access and thinking about it as creative, generative, collaborative and ongoing. That was the initial seed of the project.

As a sighted person, there’s a lot of expertise around description that I’m missing, so I’m collaborating with Bojana Coklyat, who is also a disabled artist and a screen-reader user. We developed a workshop curriculum that introduces people to alt-text and then talks about how it might relate to poetry, or how we can draw on thinking from the world of poetry in order to write more interesting and expressive alt-text. The bulk of the workshop is writing exercises, providing opportunities for people to practice and talk about it.

EM: Can you talk about why you frame it as an artistic project rather than a form of access consulting?

SF: That’s been very important for us, because the workshop is not about providing answers, best practices or guidelines. In fact, the more I’ve learned about alt-text, the more questions I have. The goal is for people to leave the workshop knowing, like all things related to access, “This is a practice and will require ongoing thinking.”

EM: What are some of the main things you’ve learned about alt-text through this project?

SF: The mainstream approach to alt-text is often like Donna Haraway’s quote about the “god-trick of seeing everything from nowhere.” Alt-text is often approached as being this neutral, all-knowing, all-seeing, “objective” description. It was important to realize how alt-text is subjective, how we’re all seeing and interpreting images differently. So, a big realization for me was that I could use the first person. In situations where there is clear authorship—on my own social media or my own website or if I make an audio guide for an exhibition—I can use my voice and be clear that I’m reporting back from my particular vantage point.

I’ve also come to understand how ableist the structures of online accessibility are. There are giant platforms like Facebook and Instagram, Twitter and Squarepsace, where millions of people are uploading content and images, yet those platforms have made the choice to not prioritize access and alt-text. They’ve made it a much more complicated and opaque process than it needs to be. There are ways to hack and work around it, but it would be great if you didn’t have to find a tiny gray text that says “advanced settings” on Instagram to add alt-text. Alt-text shouldn’t be tucked away or even marked as “advanced”.

Shannon Finnegan: ‘Do you want us here or not,’ 2020, MCA Denver, Denver, CO. Fabrication by Joshua Bemelen // Photo by Wes Magyar // Image description: A bright blue chair that says, “I focus better seated. Sit if you agree.”

EM: How can or should an artist consider alt-text in relation to their own work or practice?

SF: A lot of times institutions are more responsive to artists’ requests around access than to the requests of their own access workers. So, going back to seating, if an artist is going to make or present a video work, they can specify that it needs to have a chair in front of it. There are ways artists can build infrastructures or requests into their working practice, and I definitely think that’s true with alt-text.

When I send images somewhere for promotional use or publication, that image is already traveling with text—with a photographer credit and caption information about the title, the year and the material. So now I’m always including an image description in the caption information, or requesting that it be put in the alt-text, as a way of signaling that the description is important and needs to be kept with the image. This might also prompt further action for an organization, institution or gallery in regard to their own digital accessibility practices.

EM: Have you seen your work directly affect the access priorities of an institution, website, gallery, etc.?

SF: There are places where Bojana and I have done workshops that have then started adding image descriptions to their Instagram and website. It feels small, but it’s exciting to know a group of people have become attuned to it, taken it on and made it a priority.

Artist Info

shannonfinnegan.com

alt-text-as-poetry.net

Additional Info

The image descriptions accompanying the photos in this article were provided by the artist.