by Noëlle BuAbbud // Nov. 17, 2020

Narratives of disability are too often filtered through an ableist lens, resulting in tokenized representation. How do we begin to understand embodied knowledge and storytelling as a point of departure from normative, oppressive implications of an ableist logic? For playwright and dancer Jerron Herman, performance is an act of writing with the body in order to foreground experiences otherwise made illegible and inaccessible by current power structures. Herman choreographs new vocabularies for movement, transcending the structures and traditions of modern dance: his gestures awaken a deepened understanding of the senses and body.

Herman, an interdisciplinary artist based in New York, explores movement and performance as a site for bodies to relate and celebrate the sensory awareness of being, experienced and understood from the vantage point of Disability. In our conversation, Herman calls for an approach to accessibility that is not exclusive, rather centered around a collaborative culture of welcoming. Herman is a 2020 Disability Futures Fellow, an initiative of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and Ford Foundation.

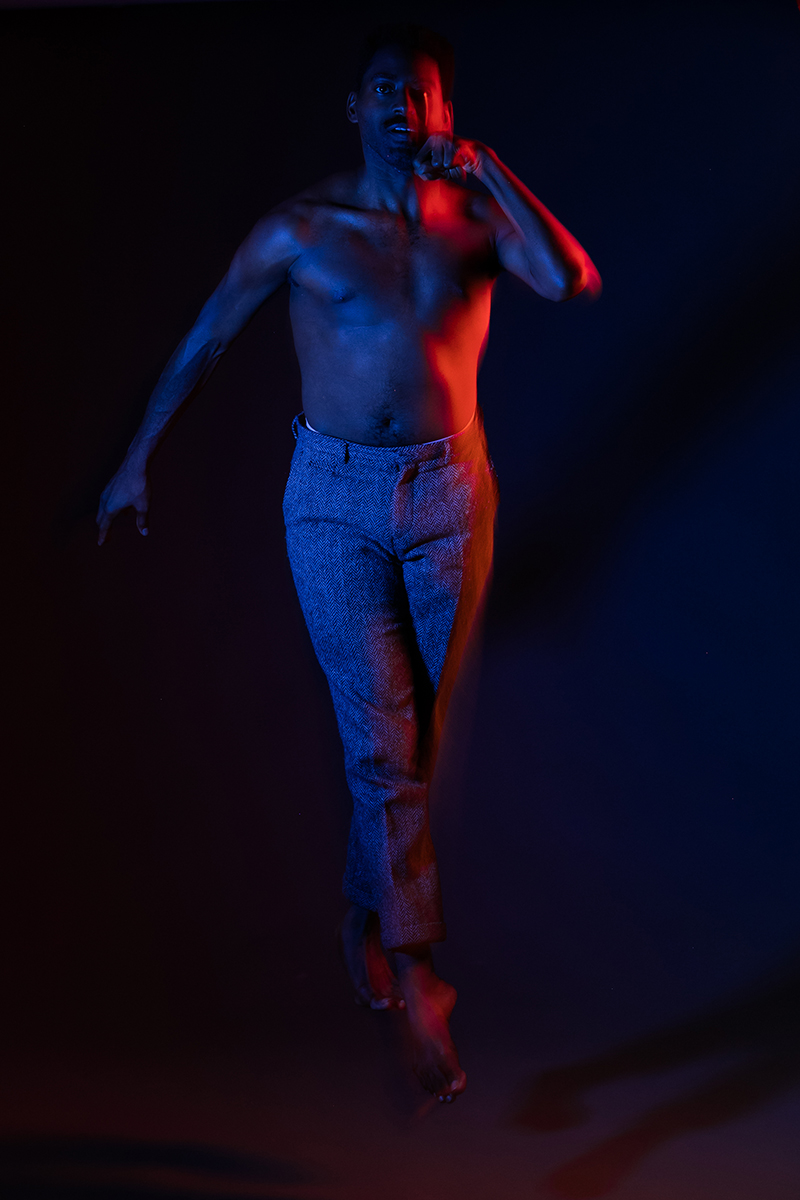

Jerron Herman: ‘Many Ways to Raise a Fist’, 2019, Performance // Credit Filip Wolak

Noëlle BuAbbud: What does meaningful progress in terms of accessibility in the arts (and world) mean to you?

Jerron Herman: Access is still largely used to talk about entry into historically exclusive places rather than as a culture of welcoming. We should retire the phrase “access to” because it upholds a power structure that isn’t as ingrained as we have been led to think. In disability communities, we create new welcoming based on individual practices and communal experiences. We demand institutions to provide it as a right, but our development of Access services or conventions is also internal, bred by us. In this way, I see the power dynamic shift to one that’s shared. Disabled artists are at the vanguard of Access culture, more than the institutions. So, meaningful progress looks like institutions listening to Disabled artists and organizers; it looks like multiple engagements beyond a tokenized one, a relationship; it looks like funding the communities to advance, critique and create their own practices of Access. I love that we are not dictated to, in this way.

NB: Can you tell us more about your background as a playwright, dramatic writer and the importance of physicality and orality in your storytelling, especially in relation to disrupting what is considered “normal”?

JH: I began writing at about eight-years-old because I wanted to be an artist but did not see myself. My older brother Jacque is a fantastic actor and always looked so secure within his collaborative while putting on a show. I wanted my collaborative. I wrote to pen my own parts and opportunities, but never really involved my disability. You could say my body was inert; instead, I was using my mental acuity to perform. It would be about five years into my dance career, having experienced awakening my body both to movement and Disability, that I returned to text, ready to imbue it with physicality. My play ‘3 Bodies’ centers on a trio of disabled rock-climbers who each have had extended embodied experiences with movement—as a daredevil, as a salsa dancer, as a paraglider—while they contend with the real threat of knocking into each other on/off the wall. Within, though, there’s the crucial subtext of knowing your body, feeling sensation. I didn’t have a vocabulary for that until I became a dancer, but now my characters and I benefit from this knowledge. My dance pieces are now equally infused with a sense of an actual text. I love transferring a theatrical composition to more abstract work. This alchemy mirrors how my own disabled physicality communicates within and beyond the bounds of modern dance’s tradition itself, to gesture at nuance. This has meant crucial new cross-discipline collaborations. I now have my collaborative.

Jerron Herman: ‘Many Ways to Raise a Fist’, 2019, Performance // Credit Filip Wolak

NB: Thinking of your 2019 performance ‘Many Ways to Raise a Fist’, how can bodily movement, physicality, endurance in all its pluralistic expressions act as a kind of resistance or protest?

JH: My great friend and artist Shannon Finnegan has been steadily questioning why bodily and physical acts of resistance—even to fatigue or tiredness—are valorized in society through their ‘Anti-Stairs Club’ series. Socially, as a Black, Disabled man, I was immediately named an activist when I did not feel my level of activity warranted such a title. In tandem, the dance world’s term “organization” seemed to name the inarticulate tremors and activities of my body as chaotic. So, people wanted this grand stance or gesture in order to read me. ‘Many Ways’ was identifying interiority. I wanted to champion subtlety and the rigor of minutiae, as these concepts also bring revolution. It was a dream to perform at the Whitney [Museum of American Art] and share these ideas. I bisected the piece into a quasi-lecture and more abstract second half to narrate the depth of ‘Protest’. The ending is an optimistic jaunt set against Aretha Franklin’s version of ‘Moon River’. It’s cheesy and joyful, but when the prevailing sentiment of progress is “grin and bear it”, this timbre felt countercultural. What about joy and pleasure and care? I strive to question what’s being said while sinking more deeply into what is the truth. So, a physicality that responds differently to a prevailing narrative is immediately resistance. The cause of resistance is cycling through many Disabled artists’ work, so we’ll be sure to see more interpretations.

NB: Nietzsche wrote about dance as a radical affirmation of life, bringing a deep sensory awareness of our power and participation in an ongoing creative reality: creativity emerging from bodily movement. In what ways could your work be seen as an affirmation and celebration of the plurality of movement/bodily experience, creating a rupture within an ableist value system?

JH: It’s not lost on me that my body is unique for a dance context or that I was not initially intended to participate in this art world, so when I dance “abandon” becomes a keyword for me. Abandonment is acknowledging a full extension and, as I fully extend in movement, I’m countering the parameters that diagnosis and convention created. I could be enlivening the parameters, too, for my benefit. I use diagnostic characteristics as impetus or research for movement, for example. This helps me transfer any generative quality from one frame to the next. I don’t have to lose anything to make anew. This is celebratory. I relay how flat a definition might be through a full, abandoned, fleshy interpretation. Nietzsche is right in that regard. Dance is an affirmation, not in the mere mechanical ability but in the breath that makes it so, the sensation of the materials underfoot, the vibratory power of the atmosphere. My work is responding both to the context of any container—Protest, Physical Education, Clubbing—as well as the ultimate container, this body. The works identify the illegible and darkened areas. Through movement, I rupture a prescribed value by adding the addendum of my flexed foot or noticeable spasm, by celebrating it. So, composition and choreography are revealing to our world that depth that is often overlooked. It’s my greatest joy to uncover something true and beautiful about myself and our world. It begins with my body; that seems the easiest beginning place.

Jerron Herman // Credit Beowulf Sheehan

NB: How can we, whether as creatives or audiences, be more effective advocates for accessibility?

JH: I believe that curiosity should propel any action. For creatives and audiences who wish to be effective advocates of Access, the culture of welcoming, I would encourage them to understand their impulse, the why, and move from there. Authenticity cannot be sacrificed in this regard because my communities are asking for relationships over transactions. There is the land of compliance that does not need relationship, but with the keyword here being “effective”, it’s crucial that one be in community with the artists and the audiences. I certainly don’t understand Access without community and don’t choose care practices outside of what I’ve learned. I have witnessed elastic ways to use ASL interpretation or audio description that are artistic, but this is after understanding its place, to begin with. Especially for audiences, I would love them to recognize that the use of these practices is not “just” for impairment but have benefits beyond who they’re intended for. I was struck when audiences reflected they’d increased in dance vocabulary after reading the transcripted text displayed onstage, which came from live audio descriptions during my performance. Noting the congruity between a possibly unknown word and the corresponding movement endeared them deeply to the piece. This is my arc as well, understanding concepts better as they are relationally revealed to me. The benefits of accessibility abound in many directions.

Jerron Herman: ‘Relative’, 2019, Performance // Credit Mengwen Cao

NB: What was it like participating in the disabled-led festival ‘I Wanna Be With You Everywhere’ (2019) at Performance Space New York, where you performed ‘Relative – a crip dance party’?

JH: ‘I Wanna Be With You Everywhere’ was like Disabled Woodstock, where the possibility and energy of this event settled into this special mandala where we were creating a new world. We didn’t know where the organizers began and the participants ended. Rather, we were all both. I had the extreme pleasure to sit on the Advisory Committee, where I really just absorbed the visionary organizing prowess of Arika UK, Alice Sheppard, Park McArthur, Carolyn Lazard, Constantina Zavitsanos, and Amalle Dublon. They made me dream. They still do. In fact, the organizing and creating and being-ness of that space have seeped into all of us who witnessed it.

And so, when I was invited to also perform, I chose to respond to the moment, to a sense of futurity. ‘Relative’ was built around my reading of Eduoard Glissant’s ‘Poetics of Relation’. His notion of “Island time” seemed so reminiscent of “crip time”, or the altered time table disabled people encounter to operate in the world. I wanted to give us an atmosphere that was, again, made legible. So collaborator Kevin Gotkin and I created a “vibe” that would allow great flexibility—hoot, walk away, join. To me, it was anti-choreography where I merely facilitated welcoming and levity, possibly simply through my body cues. As I passed through seated audiences onstage or along lighted paths, I was weaving a deliberate tapestry that was to reflect them, my people. It’s highest form was its ephemera.