by William Kherbek // Nov. 20, 2020

The creation of art is often dialogic. An artist establishes a connection with the material world or an interior discourse and produces a work in response. The work of the Berlin-based Mexican artist Manuel Solano is dialogic in both this metaphoric sense of the term, but also, often, more literally. Solano became blind at the age of 26 as a result of a treatment regime for HIV-related illness. Since that time, Solano has continued to develop a unique and powerful artistic practice centred on painting, despite not being able to see the resulting works. “I try not to think about the visual aspect of the painting,” Solano said, “because I’m never going to get what I want from them.” This realization has led Solano to a kind of acceptance: “I need to be satisfied with what they [the paintings] are to me in my mind, and the image I can derive from people’s descriptions of them.” To know one’s work only through others’ eyes is perhaps painful for an artist like Solano—whose paintings, sculptures and performance works are often searingly personal—but “the charity of the hard moments,” in the words of the poet John Ashbery, can provide new forms of understanding. Solano shared their perspectives on the ways their work is created, developed and received, and the ways such “hard moments” are experienced, managed and often overcome.

Manuel Solano, Portrait, 2019, Video, Duration: 6:21 min, loop, without sound, Edition of 3+1 AP // Courtesy Peres Projects, Berlin

William Kherbek: Pop cultural images play a major role in your work. As you often use images and references from outside traditional art historical expectations, could you tell me how this dimension has changed in your work over time, and how the kinds of accessibility—but also exclusion—that define pop culture can shape identities, expectations and receptions to your work?

Manuel Solano: In most cases with pop culture, I have to work from memory; the memories of what I did get to see as pop culture. I try to remain acquainted with pop culture now through feedback from people around me, but I mostly work from memory. I would say that, in that way, I’m kind of cheating blindness: I’m blind now but making work with references that I obtained when I was not blind. I have no idea how, for example, another blind person who hadn’t seen the movie I’m referencing, or the musician I’m referencing, would experience the description of my paintings.

Obviously, my experience of pop culture, even though I’m blind now, is a visual experience from the 26 years that I was able to see. In terms of identity, I think pop culture permeates us and makes us who we are. I’ve thought many times that people are collages of the few things that they are predisposed to, plus all of the information around them. Pop culture is particularly influential in our lives because it’s surrounding us every day and, through we might dismiss it as unimportant or mundane, a lot of our emotional experiences are reflected in it one way or another: excitement, joy, heartbreak or grief.

I remember hearing, at some point during my education in art school, that media is a metaphor for life. We put metaphors of our lives and our emotions into movies and music, etc. I think that was true at the beginning of the 20th century; I would say that now, for our generation, somehow the roles have been reversed. I would say that we see life as a metaphor for pop culture. We base our expectations on, and we measure our experiences comparing them to, what we know from pop culture. To use an example, I was very much into Alanis Morissette when I was 12 or 13 years old. And not just Alanis, but I’ve been drawn, throughout my life, to musicians who are female and who have a very strong voice and personality in their work, an otherness. I realized that I’d been using Spotify for a year and a half, but I didn’t have any Alanis in my library. So I started playing Alanis Morissette and listening to her lyrics, and I kept laughing to myself, because we are so alike. We’re both very intense and very awkward in a way, and self-deprecating. In that moment, I remember thinking, “am I so into Alanis because I can relate? Or am I the way I am, because I like Alanis?” I would say the conflict in those questions is one of the key ingredients in my work.

Manuel Solano: ‘The Rachel,’ 2020, Acrylic on canvas, 215×160 cm // Photo by Matthias Kolb, Courtesy of Peres Projects, Berlin

WK: Yours is quite an embodied process. You’ve spoken in other interviews about the use of pins and pipe cleaners as markers for the creation of works, but perhaps you could speak a bit about the way your process has evolved over the years during which you’ve experienced considerable physical change. What are some of the new directions your work is taking?

MS: My process is still very much the same. We use the same materials, pins and pipe cleaners, and strings and all of that; however, almost every canvas we make requires some degree of innovation. There’s usually one detail or one texture that we’ve never painted before that we need to figure out on the go. Like, how do we paint water in a swimming pool? Or, recently, how do we paint water dripping down from a shower while sunshine is streaking through it? Each of those challenges requires new techniques, new ways of me touching the canvases. For example, for this new texture, instead of rubbing the paint onto the canvas, I lightly tap my fingers without rubbing them back and forth.

I would say the process is always very physical, especially now that I have a big studio and I have help, and we’ve been working on very large canvases. Yet, I do find myself missing more physical means: sculpture, for example. I made a series of three sculptures last year, and I’ve been meaning to get back to sculpture ever since, but I haven’t had the time, or I haven’t had the stimulus. It seems like nobody wants me to make sculptures right now. The gallery wants paintings usually, but sculpture is definitely ten times more satisfying for me. It’s very therapeutic, actually. I can just sit down and try to shape something in clay with my hands, and I love it. Painting is such hard work!

Manuel Solano: ‘Untitled 1’, 2019, from the series ‘Hommage à Pompon’, Bronze and automotive lacquer, 62x56x11 cm // Photo by PJ Rountree, Courtesy of the artist

WK: If art is a means of self-expression, or self-discovery, it often feels in looking at your work that you’ve used art to ask questions of yourself as much as to express memories, experiences and visual interests. Perhaps you could speak about how that discovery process has taken place via the work you’ve created.

MS: It’s interesting you say that I seem to be asking questions, because it surprises me. I don’t feel like I address questions in my work. I would say it feels more like I put out answers without knowing the questions. Sometimes I get an idea for something, and I just know, part of me just knows, this is a good idea. It sticks in the back of my head for months and months, or years even. But I don’t have an a priori approach where I have a question like “I wanna address questions about my gender identity or my body, or how I feel about my body nowadays after blindness, and after scars, and blah-blah-blah.” I don’t sit down with these questions and think about the best way to address them in my work. It’s always the other way around.

WK: In that we are living through a moment where historically marginalized voices and identities are coming to the fore in contemporary art discourses. Are you wary of the ways in which blindness or other aspects of your identity may be used as an “angle” for presenting your work?

MS: Of course. Regardless of what is said about my work, or anybody’s work, and regardless of what I do, I need to always remind myself that whatever image anybody else has of me is not at all who I am, or who I want to be seen as. And I hate labels of any kind. And I would say that it does bother me when labels are used around my work, but I also understand that sometimes they cannot be escaped. For example, blindness: I don’t think blindness is what makes me an artist at all. I think I’m the same artist I always was. I think I’m doing the same work I was doing before I became blind. Obviously, the appearance of it has changed a lot, I guess, but the work is coming from the same place, and the substance of the work is the same.

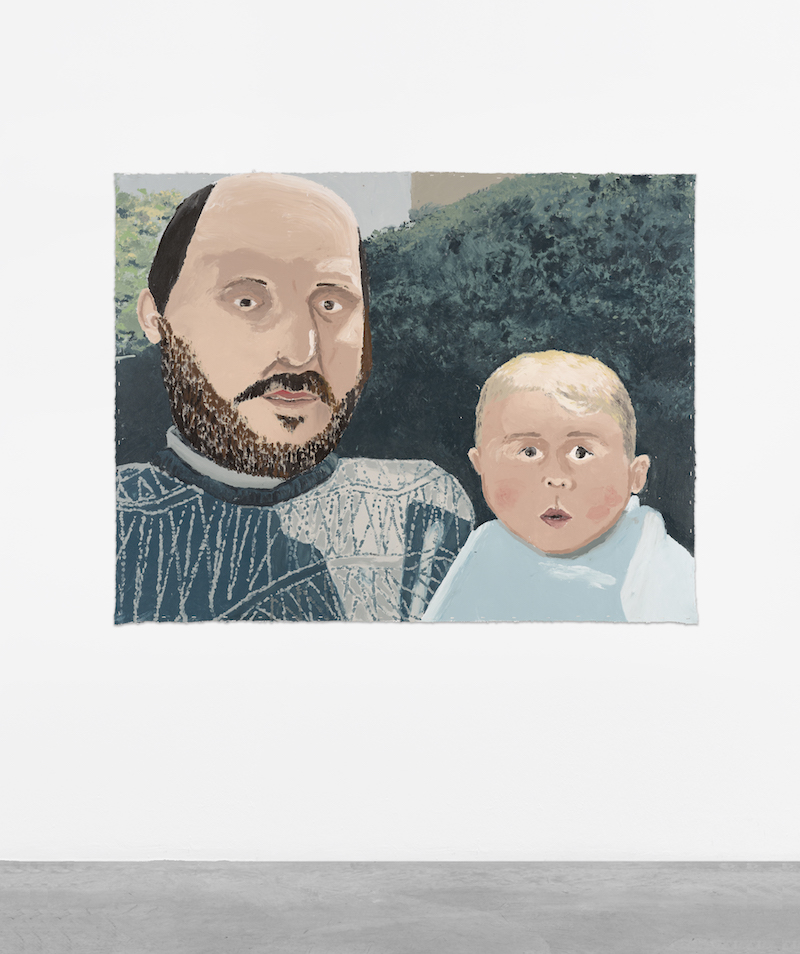

Manuel Solano: ‘Autorretrato con Papá,’ 2020, Acrylic on canvas, 131×170 cm (52×67 in) // Courtesy Peres Projects, Berlin

Ever since I decided to come out in my work as a transgender person, I knew it was going to be something I would have to fight against. Even today, I find that people use all these labels and usually the labels come before the word “artist” and I really resent that. I hate being talked about as a transgender artist or as a non-binary artist because again I don’t think my work is exclusively about gender identity. If anything, I would say Manuel Solano is the only label about my art. I make Manuel Solano Art.

Sure, it’s important to be diverse and inclusive; everybody should have a voice, everywhere, but throwing labels around, it shows that you’re trying too hard in a way. If I read a review about my work and the fact that I’m blind is mentioned three times in one paragraph, and the term “non-binary” is mentioned three times in one sentence, that’s when I realize that these people are not interested at all in my work. They’re probably not even looking at my work. They don’t understand what my work is about. They’re just wanting to appear to their audience as very diverse and very inclusionary. Shouldn’t you just be inclusionary? Shouldn’t you just feature diverse content and let it show?

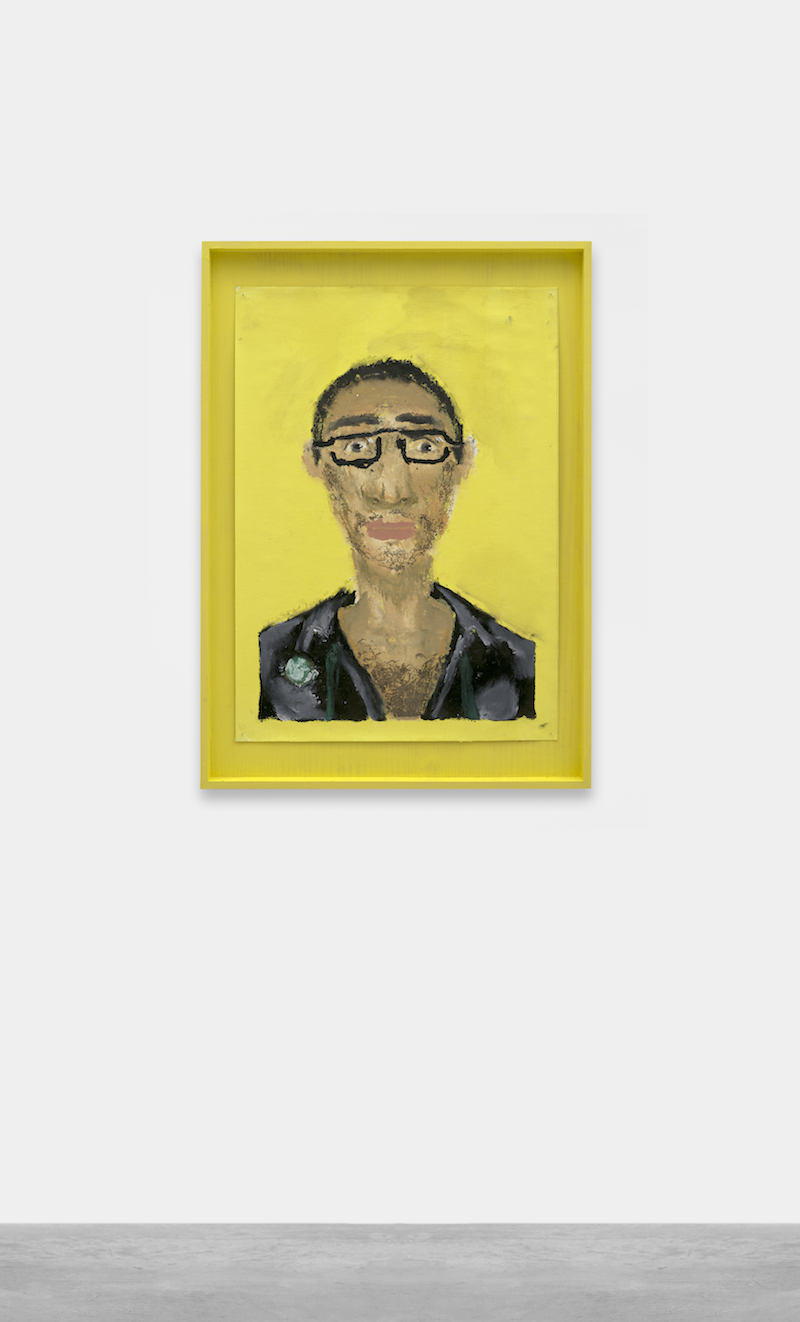

Manuel Solano: ‘The Hottie from Starbucks,’ 2019 from the series ‘Portraits’, Oil pastels and acrylic on canvas, 59 x 42 cm // Photo by Matthias Kolb, Courtesy of Peres Projects, Berlin

WK: Do you have thoughts on how Berlin can provide a more supportive and accessible culture for artists?

MS: For me, my biggest surprise and shock was learning that I could apply to the Künstlersozialkasse (KSK). I had no idea that existed when I moved here from Mexico. For many, many reasons I wanted to move away from Mexico and live in a foreign country. When I thought about living in a foreign country—and these were just dreams because I had no plans for achieving this—I wanted to find some security for my health care and my future. In Mexico, I could afford private healthcare to some point, but I was also aware that if anything very serious happened to me down the line, who’s to say whether 20 years from now or 30 years from now I’ll be able to pay for a private hospital in Mexico. Maybe I’ll fall into the hands of public healthcare in Mexico, and that’s the system that has already failed me in many ways. I’m blind partly because of that. I feel so much safer here. The day that I got my [KSK] acceptance letter, I cried and I cried and I cried, because I couldn’t believe how long my mother and I suffered with healthcare problems, ever since I became blind. It’s been my mother who has to go every month to this clinic in Mexico to get my prescriptions for retrovirals for HIV because I, being blind, cannot go by myself. It’s almost been like this penance that she and I have had to go through, and now that I’m insured in Germany, that’s over. I can safely say to my mother that as long as I’m living in Berlin, I’m safe.