by William Kherbek // Jan. 19, 2021

The representation of physical territory has a vexed history in art. The genre of “landscape” painting has long been defined as much by what it excludes as by what it includes; it is perhaps fittingly ironic that the term itself is now appropriated to describe a visual orientation of an image of any kind. If anything can be a “landscape”—viewed from this level of abstraction, even seascapes are landscapes—what must a contemporary notion of “landscape” in art include to overcome the limits of the genre’s past and its present, all-inclusive blankness?

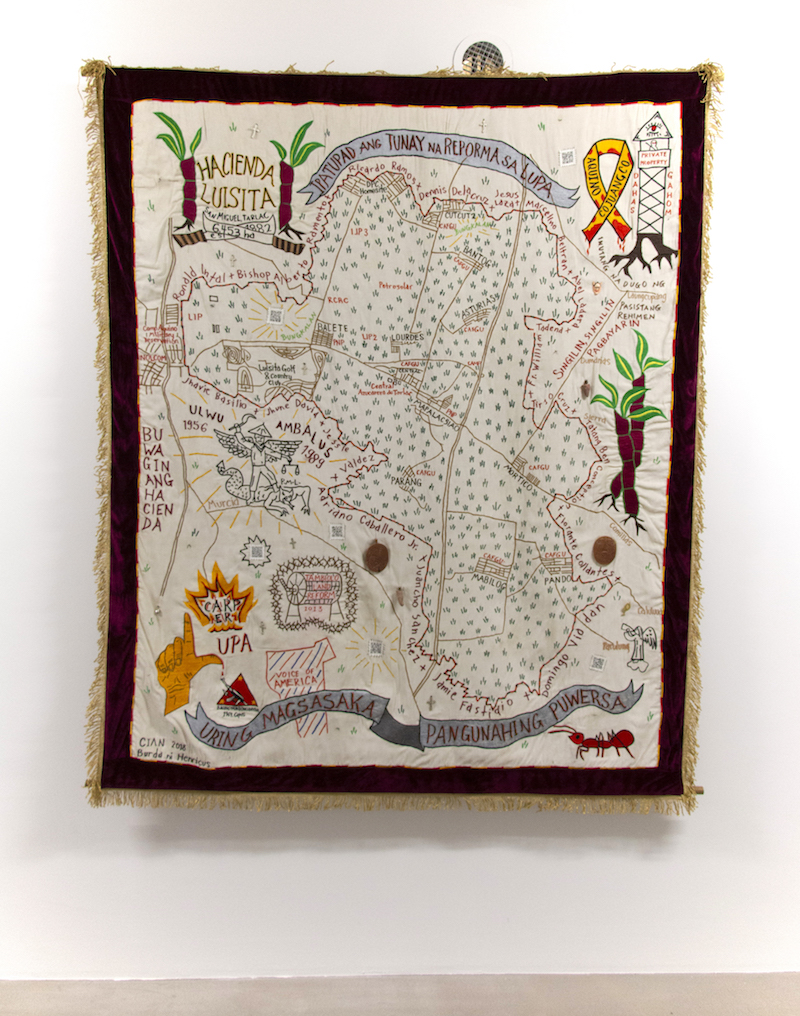

The work of Cian Dayrit, multi-media artist from the Philippines, argues fiercely for the necessity of the inclusion of the narratives of contention that define land, landscapes and territories. Dayrit’s works interrogate the ways in which art has privileged some narratives over others in the depiction of physical spaces, and how, very often, what is hidden beneath the surface image of a territory is what truly defines it. A subgenre of Dayrit’s works, known as “counter-cartographies,” explicitly examine the ways in which extractive depredations define geographies, and the ways local communities resist their exploitation. We spoke to Dayrit about how art can render the concealed visible, and the ways artists can challenge cultures of extraction.

Cian Dayrit: ‘Beyond the God’s Eye,’ 2018, installation view, NOME // Photo Gianmarco Bresadola

William Kherbek: Your work deals with extraction on a number of levels, from historical colonialism to environmental destruction, to cultural exploitation. Perhaps you could speak a bit about how the experience of translating such encompassing and (literally) all-consuming dynamics of exploitation into art has functioned for you. How do you understand the artistic response to these forces? Is it a kind of witness, a kind of making-visible, or a kind of exorcism? Maybe all of those things?

Cian Dayrit: Between visualising and exorcising is an elaborate process of awakening into, enduring and participating in a struggle that is way bigger than an individual experience. One’s own sensibilities and conditions are not enough to comprehensively understand, let alone translate, the encompassing effects of systemic historical oppression. One must develop a deeper connection to human experiences and recognise the material conditions that dictate these narratives. Only in solidarity with the struggles of the people can we truly translate, at least, dynamics of exploitation.

Cultural work should not be detached from reality. The question is how can we expand the scope of cultural work from the constraints and contradictions of contemporary art to influence the realities we recognise, and attempt to reflect and respond? It’s something I’m learning along the way.

Cian Dayrit: ‘Et hoc quod nos nescimus,’ 2018, Embroidery on textile (collaboration with Henry Caceres), 103 x 153 cm // Photo Gianmarco Bresadola

WK: The map plays a significant role in your work, so its history as a tool of exploration, and a tool of exploitation, is intrinsically brought to bear on your works involving it. Could you discuss the status of maps in your work both in relation to their positions within extractivist narratives, but also how your “counter-cartographies” have sought to repurpose—perhaps even de-purpose—maps?

CD: My work is not solely based in the format of, or on the literal gesture of, mapping, but rather in highlighting the under-represented narratives of struggle, particularly in a global south context.

The map and its contexts and poetry, however, definitely plays a significant role in my goals. It is not so much to “de-purpose” the mapping tool, but rather to subvert its functions, which are relentlessly coopted by oppressive forces. Maps, and any other objects, could be activated, and even weaponised, to serve specific agendas. In the case of my work, I use the maps to serve the people.

As I develop my language and understanding and participation in the struggles that I tackle in my works, the “maps,” too, evolve from representing space to representing existing material and social conditions as defined by the perspectives I subscribe to, [those] of the marginalised classes.

Cian Dayrit: ‘No Flag Large Enough: Colonizer,’ 2020, Embroidery on textile (collaboration with Henry Caceres), 110×155 cm // Courtesy the artist and NOME, Berlin. Photo by Nicola Morittu

WK: Along a similar line of thought, a lot of writing about your work speaks of it as a kind of “excavation” of histories and narratives. I wonder if you see your work that way, and, if so, if you’d like to describe the ways in which “excavation” and “extraction” function differently.

CD: I find it funny how the word excavating has been used several times in writings about my work. It is because some of my first projects were looking into the practice of archaeology and the role museums played in legitimising certain dominant perspectives regarding heritage and nationhood. I’ve since been looking into how the language of power and dominance and control is reproduced by institutions via objects and traditions. Perhaps “excavating” is an apt word for my practice, as I seek to unearth narratives, from archives to personal narratives, from the ground. My work will always take the form of a somewhat extractive practice, insofar as it is kept critical to centralised bodies, such as the state or corporations, which assume a sort of monopoly on extractive practices that become exploitative.

WK: The counter-cartographies often deal with extractivist activities in the Philippines. Could you speak about the specific Philippine milieu in which these works were created and the issues they treat?

CD: The Philippines is rich in natural resources but it is being over-exploited by imperialist states. The ruling class alongside multinational corporations control the resources with unequal treaties and militarism. The peasant sector, which makes up most of the population, remains landless. Indigenous populations are driven out of ancestral lands to make way for aggressive development projects. Neoliberal policies prevent the state from industrialising, despite the fact that we have more than enough natural resources [to do so]. Social services remain privatised and inaccessible to most of the population. Catastrophic ecological degradation and food insecurity continues as land and waters are exploited for business.

There is resistance in varying levels. For a society as described, it is only natural for the people to organise and mobilise for social justice and liberation from oppressive conditions. One such example of resistance is the armed struggle in the countryside, which is the longest protracted peoples’ war against the puppet regimes. At the start of the [Rodrigo] Duterte administration, there was hope when peace talks between the government and the National Democratic Front of the Philippines commenced, and resolutions have been drafted to address the roots of the armed struggle. The CASER (Comprehensive agreement on socio-economic reforms) was written to outline the roots, and possible solutions, to decades of unrest stemming from centuries of colonisation. Unfortunately, Duterte stopped the peace talks and declared the NDFP, and all its allied organisations as terrorist groups. All this while human rights violations, foreign debt, immense corruption and the exponential erosion of Philippine society persists. Every day is a test in perseverance, vigilance and survival but we continue to endure and serve the people.

Cian Dayrit: ‘Tropical Terror Tapestry,’ 2020, Embroidery on textile (collaboration with Henry Caceres), 200×230 cm // Courtesy the artist and Collection Servais. Photo by Billie Clarken

WK: Extractivist logic is intrinsically zero-sum in its principles; the contemporary art scene is infused with the same kind of “scarcity logic” of extractivism in some ways, but it can also function in opposition to extractivist mentalities, emphasising a kind of plurality and an “abundance mentality” supporting the proliferation of interpretations and perspectives. As someone who convenes workshops and other forms of expanding artistic participation and discourse, how would you say structural barriers play a role in limiting the capacity for art to effectively oppose or challenge extractivist logic?

CD: Any gesture that transcribes, and attempts to synthesise, narratives can be extractive and to some degree exploitative. My presence in the workshops is inevitably intrusive and may seem like a position of dominance no matter how much I try to avoid it. So, how can we angle our inevitably intrusive gestures to oppose extractivist logic? Maybe it is not the logic per se that we are trying to challenge, but rather the conditions in which this logic is (ab)used and contextualised to serve the interests of corporate greed.

When I convene the workshops, I introduce myself as an artist first, and then my affiliations. This approach helps to contextualise the workshop as a creative activity, but, at the same time, to support the idea that with this activity the participants are free and encouraged to articulate their struggles and to orient themselves in terms of conditions: access to resources and services, spaces and livelihood, experiences with aggression from different groups, among other topics.

Art disarms the workshops, the workshops arm the art. The art, then, can help arm the people.

When workshop materials find their way in exhibition settings, we could also consider this as extracting the potential of contemporary art to tackle themes that critique the super-structures of politics, economy and culture. The workshop itself I consider to be part of my artistic, as well as activist, practice, wherein documentation, material and copies of the maps are presented within an exhibition. The narratives and stories I learn inform the work that is created in the studio.

Cian Dayrit: ‘Mapa de la Isla de Buglas,’ 2017, Tapestry. Mixed media and embroidery on canvas, collaboration with Henry Caceres, 197×156 cm // Photo: Aage A. Mikalsen / Kunsthall Trondheim, courtesy the artist

WK: Another element of the “scarcity” logic that informs the art world is the way forms of production function within it, in terms of demands placed on artists to produce, and the way individual works are often fetishised or commodified. As an artist who approaches material forms and media in distinctive ways, could you offer some thoughts on the ways in which choices of media and formats of display feature in your works?

CD: It has become a default logic, of course, especially now that we have come to recognise that to be an artist is to participate in a world of consumption. In the case of art, we are constantly producing and consuming luxury goods accessible only to a few. And there are many ways in which we can challenge this logic.

I’ve always viewed the objects I make as byproducts of the research and solidarity work that I participate in. The works that show up in galleries and museums were made or presented specifically for the purpose of exhibition, but my practice, I like to think, both precedes and goes beyond the “exhibitionary.” Art making shouldn’t be limited to making art objects. We should all be aware of the contexts and conditions in which cultural work is conceived, produced, reproduced and consumed, so as not to let our practice be extractive and, ultimately, exploitative. Once the exhibition objects end up in collections or back in the studio, or wherever, their afterlives can still be moulded and re-digested in different formats. The narratives that were used in making the work shouldn’t just end up in the artist’s archive. They should constantly evolve and [offer] further solidarities with the communities they represent. It may be via campaigns, education or direct action. There is so much more artistic practice and cultural work can do beyond the exhibition.

This article is part of our feature topic of ‘Extraction.’ To read more from this topic, click here.