From the Seaweed Appreciation Society International (SASi) to the Forum of Sensory Motion to a shared practice called Biomutualism, Australian artists Jessie French and Lichen Kelp keep themselves knee-deep in research—and the ocean. Kelp founded SASi in 2019 “with the aim of creating a mobile studio lab and inviting marine scientists, artists, designers, architects, writers and chefs to join group seaweed explorations as a creative way to raise awareness for this often-overlooked organism,” she says. French soon joined the collaborative team, which often takes trips to investigate, research and explore the properties of various seaweeds and algae as well as hosts events with seaweed-based food and drinks.

Kelp and French’s shared interests in ecologies and interspecies relations soon led them to develop a shared artistic practice, which they named Biomutualism. Within this framework, they’ve created both functional and experimental algae-based bioplastics, and they even traveled to Morocco to trace the source of the agar (a jelly-like substance extracted from red algae) used to make it. Here, they speak about their individual and collaborative artistic practices along with their desire to explore interspecies relationships in ways that are as non-extractive as possible.

Installation view of Biomutualism’s exhibition ‘Seaweed Future: Red Gold’ in Marrakesh, Morocco, February 19-27, 2020, part of the 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair // Photo by Jessie French

Berlin Art Link: Let’s start with the obvious: What initially drew each of you to seaweed?

Lichen Kelp: Around 2015, to coincide with my return to art after a 10-year hiatus, I changed my last name from Kemp to Kelp as a wordplay on my first name. But then I started reading more about seaweeds and submerging myself deeper in the aquatic world, becoming more and more interested in marine algae. The kelp research informed my work as I became interested in an algae transformation—not just for myself and my own art practice, but for potential ecological regeneration.

The other in-road to becoming seaweed-obsessed was a series of art pilgrimages—as part of my practice, I run traveling residencies under the name “Forum of Sensory Motion’—to witness the mating displays of Giant Cuttlefish in South Australia. Diving with the cuttlefish and seeing them shapeshift, including camouflaging against their seaweed backdrops, sparked a passion for cephalopods that led to a desire to protect their marine habitats.

Giant Cuttlefish seen during the Forum of Sensory Motion’s trip to Whyalla, South Australia // Photo by by Scott Portelli

Jessie French: Between climate science literature, post-denialism and a healthy dose of speculative and science fiction, I’m interested in new ways of living on this damaged planet—which we humans are largely responsible for—among other living things. In 2015, I began beekeeping and gradually became part of the natural beekeeping group Honey Fingers Collective. We explore the intersections between farming, food, art, history, design and education, and I learned the honeybees that humans rely on to pollinate up to 80% of our staple food crops are facing population collapse. If bee populations continue to decline, we will have big problems in sourcing enough nutrients to keep humanity healthy; for example, most human sources of vitamin C are currently pollinated by these bees. And this is where seaweed comes in: Below the water, there is a plethora of other sources of nutrition. However, many of these sources face similar issues to the bees with threats due to warming, acidifying oceans, proliferation of other species of ocean flora, pollution and some human fishing practices. So, my interest in seaweed grew from the similarities and links between the threats that many species of plants and animals face at the moment, as well as the opportunities for change.

BAL: How does SASi overlap with and relate to your own practices?

LK: SASi explicitly shares many of the aspects of my other projects, such as the Forum of Sensory Motion, a performance group I’m in called Kelp D/J and the aquatic research-based aspects of my solo work. But SASi also allows for a truly collaborative space, where the focus is shifted off artists, curators and individuals and onto an organism that is struggling in a human-centric world, as well as celebrates a collective desire to advocate for our oceans.

Seaweeds found during Seaweed Appreciation Society International’s seaweed forage at Point Cook Coastal Park, September 2019 // Photo by Chris Rockley

JF: The learning and research I’ve come across through SASi have given me ideas that have led to the investigation of the material potential of algae. For example, I use red algae as a natural polymer to explore sustainable replacements for single-use petrochemical plastics: a move from petroleum, which is made from extremely old algae, to new algae, which has the potential to promote habitat regeneration for ocean-dwelling critters, reduce ocean acidification and provide a multitude of more sustainable options for above-grounders.

More generally, my work explores the value of the ephemeral, of things that don’t last as valuable, over the obsession with lifetime guarantees that exist without any consideration for the impact of such everlasting durability. How can an object like a BIC pen casing, which will leave a geological mark lasting an epoch, be so readily available and priced so cheaply without any consideration of its everlasting environmental burden? Through my work—both material research and performative production—I engage with and confront contemporary environmental crises and propose everyday solutions within the frame of human production and consumption, presented as a story of a possible future.

BAL: Beyond SASi, you have a shared practice called Biomutualism. How did that come to be and what’s its purpose?

LK: In the early days of SASi I devised the name “Biomutualism” for a curated group festival project that Jessie produced, and we had also started working together on some on-land seaweed farming experiments. Jessie was then invited to attend a residency in Morocco, and we decided to apply together. By the time we were accepted, our experiments had devolved and evolved to working with bioplastics. Through our research, we were excited to discover that the agar used to make bioplastics is predominantly harvested in Morocco, so we decided to go there and start the first Biomutualism project. The title references the desire to explore symbiotic, interspecies relationships in ways that are as non-extractive as possible.

JF: Biomutualism really developed as a way to transform some of the collective research of SASi into physical projects that explore the conundrum of living among other species. We had multiple ideas at the beginning—from tree-planting parties to seaweed spas to mushroom-leather garments and algae farms, as well as experimenting with the materiality of seaweed—and when we were invited to Morocco for this residency, it seemed like the perfect opportunity to develop this new project. We began experimenting with bioplastics in Melbourne and then, in Morocco, we traced the supply chain of the agar right back to the ocean.

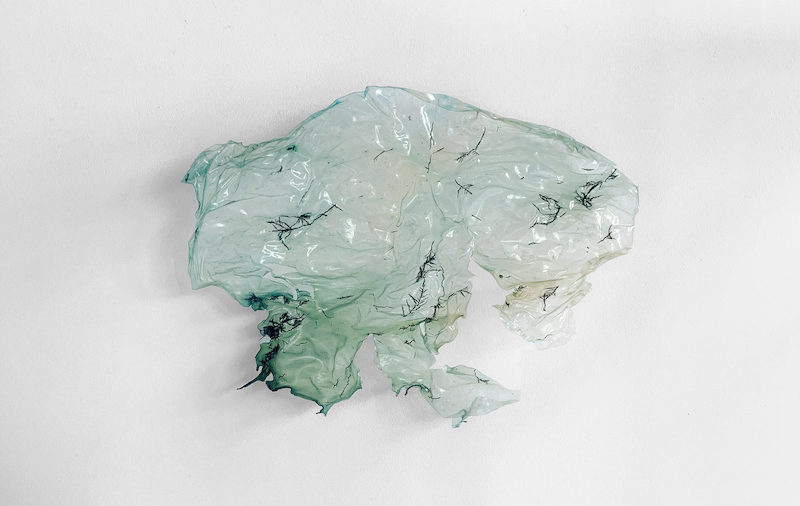

Biomutualism: ‘Red Gold,’ 2020, Algae-based bioplastic, mineral pigment and gelidium sesquipedale. Exhibited in ‘Seaweed Future: Red Gold,’ Marrakesh, Morocco, February 19-27, 2020, part of the 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair // Photo by Jessie French

Installation view of Biomutualism’s exhibition ‘Seaweed Future: Red Gold’ in Marrakesh, Morocco, February 19-27, 2020, part of the 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair // Photo by Jessie French

BAL: Much of the information about SASi and Biomutualism stresses the importance of seaweed’s sustainability. What are some alternative uses for seaweed, like making bioplastic, and how is it sustainable?

JF: When it comes to the seaweeds used in my bioplastic work, I research and try as much as possible to ensure the sustainability of materials. I grow my own micro-algae in bioreactors at home, and the red algae used for producing agar, which I use as a polymer, is what we were concerned with investigating in Morocco. Scientific journals have actually documented global shortages of this type of agar, which is also used bacteriologically, due to over-harvesting, but there wasn’t much follow-up information available. So, in Morocco, we not only traced the supply chain but also met with a range of marine experts, agricultural scientists, people developing aquaculture initiatives, local harvesters and directors and lab technicians working at the only agar processing plant in Africa. We discovered that the industry had worked with marine experts and the Moroccan Government to set up independent controls and a permit system for harvesting which has been effective in sustainably protecting seaweed harvesting. Nothing is harvested if there isn’t enough, and harvests are more than a year apart.

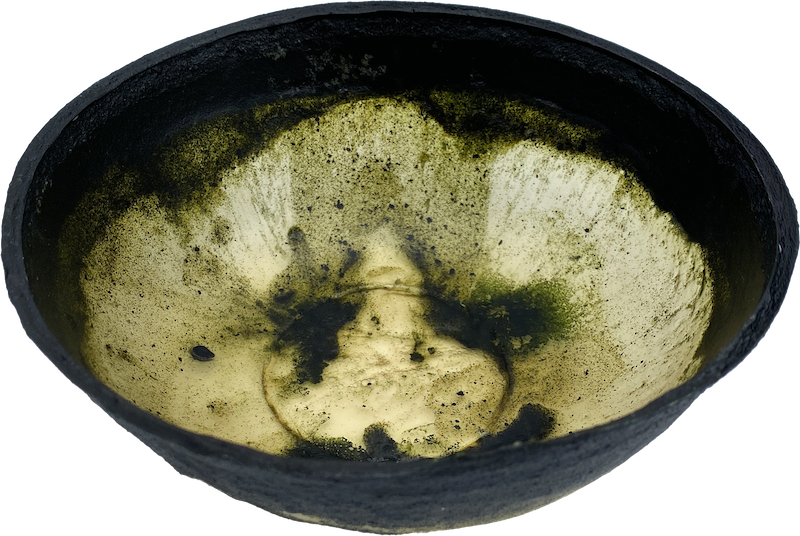

Jessie French, algae-based bioplastic bowl colored with Spirulina micro-algae, 2020 // © Jessie French

BAL: Sustainability is extremely intertwined with the topic of extractivism. How do you view your practices in relation to extractivism? Or how do you work against what could very easily become extractivist tendencies?

LK: In material-based sculptural work, like the exhibition of seaweed-based bioplastic works we held in Marrakech at the end of our residency, there is inevitably some extraction. But we were careful to investigate this closely as part of the process, primarily by researching the sustainability of the agar harvesting and the balance with working on a material that has a lighter impact than the petroleum-based plastic it aims to replace. Jessie has continued this work and is now looking at other materials that have even lighter impacts, like coffee grounds.

Some of the ways I am addressing, or attempting to address, extractivism in my own practice is by focusing less and less on material outcomes. I have become more interested in research and curating group trips, which, in addition to the Forum of Sensory Motion, has also led to establishing the “School for unTourism,” a project and business based on sustainable, artist-led tourism. Also, one of my main interests going forward with SASi is to return to the idea of seaweed farming, although I am not interested in the commercial version; I would like to attempt to have a few kelp lines out in the Southern Ocean as a way of benefiting marine habitats through small-scale marine permaculture.

JF: We have a lot on our shoulders, being humans. If you take an objective view of everything on this planet, you’ll likely come to the conclusion that we have taken more than our fair share of everything. It’s not a good look, particularly when it comes to natural resources. Sustainability is entwined in this because when practiced well, things are in balance; what is taken is never more than what is needed to re-grow the supply. My work is concerned with looking at ways to maintain that balance—to use materials that are able to be sustainably grown, harvested and produced; to make use of things that otherwise would have not been used at all, like byproducts of other forms of production that are labeled as “waste”; and to ensure that the things produced are not extractive, taking up everlasting space in the environment as landfill or trash polluting the landscape and waters.

It is this latter part of extractivism—the trace of a product—that my work draws attention to. Disposable plastic products made for momentary use not only extract through their production, but they also continue to extract space and health from the environment, as they last lifetimes longer than the people responsible for making and using them.

Jessie French drinking from an algae-based bioplastic cup, 2019 // © Benjamin Thompson

BAL: What do you think about the overlap between art and science?

JF: I actually returned to university last year to study history and the philosophy of science, particularly because I am interested in this overlap. If we wade back through time, sometimes artists have been the ones to make scientific discoveries. Renaissance artists, for example, were investigating human anatomy at a time when practicing anatomists were still accepting Galen’s writings, which were based on the dissection of animals. Additionally, sometimes scientists’ artistic skills have aided their scientific practices, like Santiago Ramón y Cajal, whose artistic skill and way of seeing through the microscope led him to make major contributions to our understanding of neuroanatomy.

Now, we have a post-truth world. We are living amidst post-denialism—no argument is made, no facts are presented or proven; a Tweet, headline or statement announces something as fact and many people believe it as such. Science is the closest thing we have to truthful knowledge. We need science to pursue knowledge to the best of our abilities, and we need art to digest, interpret and say something about the things around us. This is what I try to do with my work.

LK: I feel it is inherently recognized what science has to offer art, in terms of endless inspiration, psychedelic perspectives, material and technological developments and so on, but I think there are also wonderful, shared curiosities, processes and methodologies between the two fields, and the potential for experimental artforms to inform science could be explored further.

Personally, I view myself as an artist exploring scientific principles. I Iove learning through play, haptics, immersion and phenomenology. To learn and experience in this way is often more rewarding for me as part of a group, I sit uncomfortably with the solo studio artist model and prefer to share and create opportunities by creating group projects, events and holding or partaking in residencies and collaborations. Connecting with others who have different backgrounds and skills but shared preoccupations keeps up momentum, makes for great adventures and often spurs unexpected and fantastic results.

This article is part of our feature topic of ‘Extraction.’ To read more from this topic, click here.

Artist Info

jessiefrench.com

lichenkelp.com

seaweedappreciationsociety.com

Seaweeds found during Seaweed Appreciation Society International’s seaweed forage at Point Cook Coastal Park, September 2019 // Photo by Chris Rockley