by Denisa Tomkova // Feb. 12, 2021

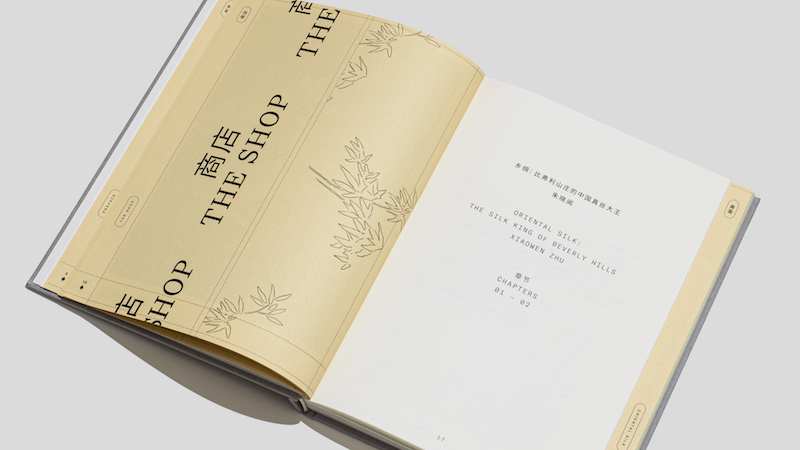

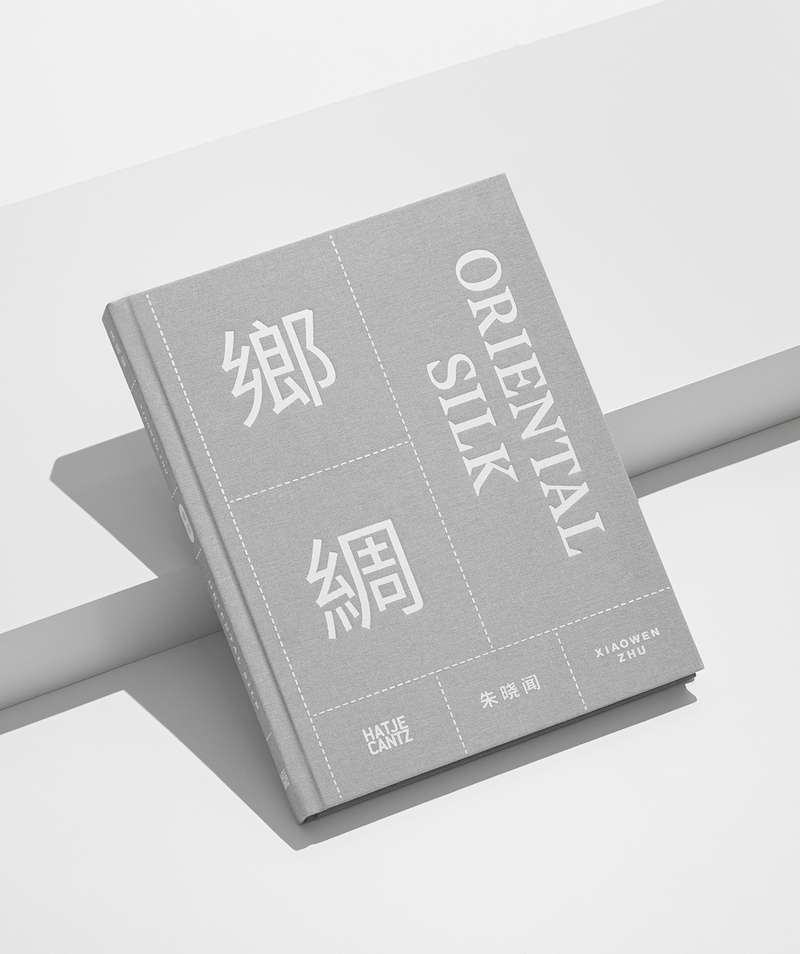

The first thing that caught my attention when I received a copy of Zhu Xiaowen’s ‘Oriental Silk’ book was how beautifully designed it was. The pages that have text on them are narrower than the pages with the images. The book is framed with stitching lines resembling those found on fabric. It’s divided into chapters using different pastel colours for each, mimicking colour swatches in a fabric shop. All these small details remind the reader that they are holding an artistic object in their hands, where the aesthetics are as important as the content of the book.

Zhu Xiaowen is a Berlin-based artist and writer. She is a self-described visual poet, social critic and aesthetic researcher. When she lived and worked in Los Angeles as a visiting artist, she came across Oriental Silk Importers, a shop run by Kenneth Wong. And that’s how the multi-media art project ‘Oriental Silk’ started. The project consists of video, installation, textile, photography and, now, a book. ‘Oriental Silk’ reflects on Chinese American migration legacies and the history of the silk trade from Wong’s perspective. The ‘Oriental Silk’ film was released in 2015 and gained critical attention at the Mexico International Film Festival, where it was awarded Best Documentary Film. The book was published in 2020 by Berlin-based publisher Hatje Cantz.

Oriental Silk Book Video from Xiaowen on Vimeo.

Denisa Tomkova: How did the project ‘Oriental Silk’ start and why did you decide to make both a film and a book?

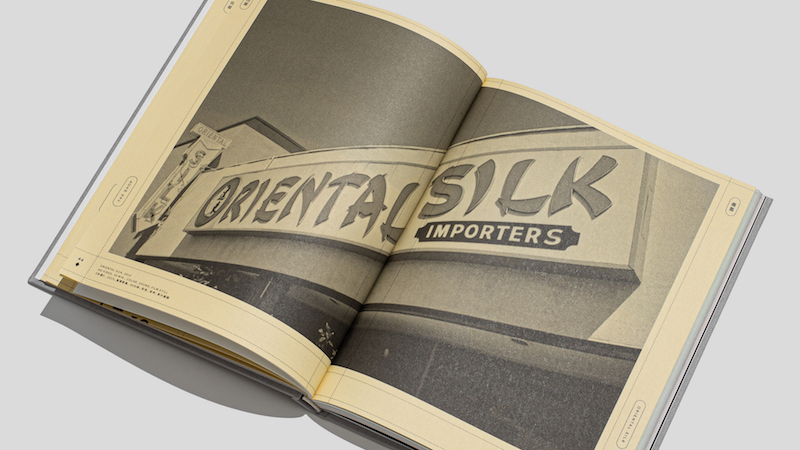

Xiaowen Zhu: Between 2012 and 2014, I lived and worked in Los Angeles as a visiting artist. It was a pure fluke that I came across Oriental Silk Importers, a shop that in its day had served as a magnet to Hollywood’s showbiz celebrities, aristocrats, as well as famous designers and big manufacturers. Anna May Wong, Madonna, Jacqueline Kennedy’s designers and the costumers of ‘Titanic’ and ‘Star Trek’ have all been frequent visitors. What will happen to this family-run business, when the shop owner Kenneth Wong will retire in his 70s? Who will remember the legacy of Oriental Silk and the remarkable 20th century Asian-American migration story it represents?

Motivated by these questions, I began filming in 2013. Then, from 2015, the ‘Oriental Silk’ film was shown in a number of places, from Shanghai to Beijing, from LA to New York, from London to Berlin.

At the same time, I recorded this story in written form. I feel films are more fluid, but the written word is more profound. As an artist, to be able to use two different media to convey the same story allows me to come at it from different angles, and to keep finding new aspects of the story that move me.

Xiaowen Zhu: ‘Oriental Silk 鄉綢’, 2020, Hatje Cantz, English, Chinese // Graphic design by Studio Cheval

DT: Can you tell us about the book’s design concept, created by Michael Mason of Studio Cheval? Why was the design of the book important for you in this project?

XZ: I’m glad that you brought up the design aspect of ‘Oriental Silk 鄉綢,’ which was developed by Michael Mason and I, step-by-step, for about a year. In the beginning, I had the idea to make a “book inside a book,” because of the multifaceted nature of the project: Kenneth Wong’s oral history of his family’s migration history, the inspiration that I draw from my diasporic experience, my fascination with chinoiserie and the aesthetic study of orientalism, and much more.

When I told Mike about this idea, he was very excited and immediately dived into the research. After months of development, eventually, we focused on the following design directions: dividing the book into chapters with pastel colors referring to Chinese American takeout menus; hand tracing weaving patterns from silk swatches found in Oriental Silk as ornamental and visual narrators; juxtaposing Chinese and English texts on the same page spread to create a sense of dialogue; beginning with black-and-white images and evolving into colorful pictures; carefully considering the choice of typeface, paper, binding and every single detail that goes into the production.

I am incredibly fortunate to have been able to work with Michael, thanks to not only his talent, but also his can-do attitude and detail-oriented mindset. Most importantly, he is extremely skilled in translating my artistic vision into a tangible design solution. He’s a dream designer to work with.

Xiaowen Zhu: ‘Oriental Silk 鄉綢’, 2020, Hatje Cantz, English, Chinese // Graphic design by Studio Cheval

DT: Your documentary film depicts the very intimate story of Kenneth Wong, the owner of the Oriental Silk business. He tells a story of how his family emigrated to the US and shares the experience of being asked questions by the authorities upon their arrival. Ken Wong recalls what his dad once told him: “If life was better in China, I would have never left. In order to survive and to raise my family, I had to come to this country.” Why did you decide to tell this 20th century migration story through the lens of these very personal testimonials and experiences? What larger implications does this story have as a microcosm of the history of the silk trade?

XZ: In documentary filmmaking or art-making in general, you don’t usually know how the story will unfold until you go through with it. This is the case with ‘Oriental Silk.’ At first, I was fascinated by Kenneth Wong as a character, who was trained as a computer engineer at UCLA and gave up his engineering career to take over the silk shop from his parents. Then, during the filming and editing process, I realized more and more, how representative his family history is, in relation to Asian American migration in the 20th century. According to Kenneth Wong, his family is from Toisan. Ninety-five percent of the Chinese emigrants from Toisan moved to the United States through chain migration and family ties. It began with the gold rush in California and then the railway construction. After that, they started to run laundromats or restaurants. That’s the general narrative that also applies to Wong’s family, the same trajectory. So there’s a lot more to Ken’s personal story if you look at the larger picture.

The history of the silk trade is touched upon in the book as well, especially during the Cultural Revolution in China (1966-1976): how did Oriental Silk import silks from China to America when there was no official trading? Readers can discover more from my book.

DT: In the book, you say that: “Filming a documentary, for me, is not an objective record; objective information has to be filtered by subjective understanding in order for a clear structure of ideas to emerge.” This project looks macro at micro, reflecting Chinese American migration legacies from the oral history of the shop owner, Kenneth Wong. The project then somehow encompasses both positions—subjective/objective, micro/macro—in a very delicately balanced act. How and why are both these perspectives important for you in telling the Oriental Silk story?

XZ: When I grew up in China in the early 1990s, the mainstream ideology was very dominated by a single voice. So, at a young age, I learned to question what I’d been told and what had been hidden. I find the contradiction in human memories utterly fascinating. This is why, when I edited Kenneth’s interview, I intentionally kept self-conflicting narrations.

In terms of subjective/objective, micro/macro, I think that’s the nature of memory and understanding. We create an order out of our memory based on the narratives that we preserve about our past. Through my film and book, Kenneth was able to reconstruct that story of family, of self, as he wanted to construct it. His refusal to give up the family legacy and the meaning of silk to his emotional past is what constitutes his identity, his being. When we reach a certain age, what more can we hold on to, other than these reconstructed memories?

Xiaowen Zhu: ‘Oriental Silk 鄉綢’, 2020, Hatje Cantz, English, Chinese // Graphic design by Studio Cheval

DT: Towards the end of the book, you describe how Kenneth Wong was keeping the shop open a day at a time, hoping that the customers will rediscover the beauty and craft behind the silk products. At the same place in the book, you reflect: “I really wanted to tell him that although he had top quality goods and wonderful stories, he needed to adapt to modern marketing methods.” From the final notes in the book, we learn that Ken Wong officially retired and sold the business in May 2020 and that Oriental Silk now has a new owner. How do you reflect on the Oriental Silk journey through your personal experience by filming it?

XZ: I am really happy for him. In today’s economic landscape, how many small business owners can retire and live happily ever after (relatively speaking)? It’s especially a relief for friends of the shop that the new owner of Oriental Silk will keep selling its inventory. So, it’s not another story of being gentrified by a big developer. As the storyteller of Oriental Silk, I feel that this is a realistically happy ending.

Artist Info

www.zhuxiaowen.com

www.hatjecantz.de/xiaowen-zhu-oriental-silk

Oriental Silk Trailer from Xiaowen on Vimeo.