by Nina Prader // Apr. 6, 2021

The message and title of Audre Lorde’s famous essay ‘Poetry is not a luxury’ has renewed relevance: like breath, poetry is vital for survival. Spiritual and repetitious, it is also ritualistic, often enacting a ceremony for commemoration. Reading and writing poetry involves the creation of verbal monuments. This notion is mirrored in the life and actions of Semra Ertan, an activist and poet. Born in Turkey, she moved to Kiel to be with her parents, so-called “guest workers” in Germany from 1960–80. In the 70s, she worked as a draftswoman, but expressed her activism and her determined spirit in her creative writing. Her work was never formally published in her lifetime and, in 1982, in protest against systemic racism in Germany, she set herself on fire in Hamburg.

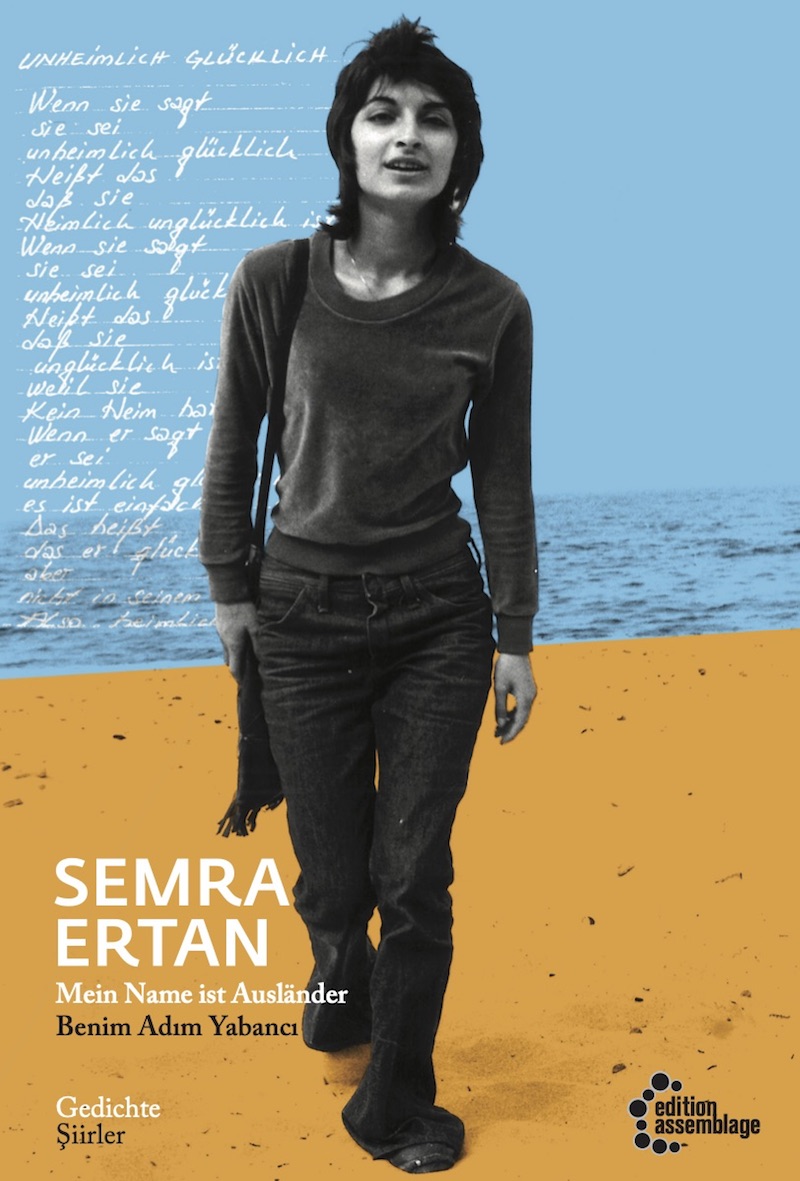

Now, 38 years later, her family—her niece, the artist Cana Bilir-Meier; her sister, the children’s therapist Zühal Bilir-Meier; and her nephew, Can-Peter Meier—have collectively published and co-edited a bilingual book of her poetry, entitled ‘Mein Name ist Ausländer | Benim Adım Yabancı.’ In German and in Turkish, the book redefines her social narrative. Semra Ertan’s dynamic legacy, knowledge and experience is now finally visible to the world. The book’s cover shows Semra Ertan on the beach in Kiel: she seems to cross from sea to sand, walking towards the reader. We spoke to her niece, artist Cana Bilir-Meier, about the publication of the book and what Ertan’s poetry means today. Semra Ertan was recently honored with the Alfred Döblin Medal for her posthumously published volume of poetry.

Cover image of Semra Ertan’s ‘Mein Name ist Ausländer | Benim Adım Yabancı’ // Courtesy of edition assemblage

Nina Prader: How did you go about preparing to publish this monument to Semra Ertan, your aunt?

Cana Bilir-Meier: I cannot even name a date when we started working on the book. It started the moment I first heard about Semra in our family. The work began in my family when I was not even born yet. I knew these poems needed to be published.

Semra had prepared everything. There were a lot of notebooks, some chronologically ordered. The poems were ready. Shortly before she died, she wrote a letter to a publisher in Germany, trying to persuade them to publish her work. She left her poems to us to publish.

NP: What was the publishing process of this book like?

CBM: There were so many chapters in working on this book, but it feels like it will never be quite finished. An English translation is on the horizon.

First, we thought about who could translate the book from German to Turkish, from Turkish to German. We asked some people, but the translation was missing Semra’s soul. It is not that they could not do it, they were great, professional translators but it was a hard and at times painful process to realize that it was our job.

Eventually, it was a revelation to recognize: my mother needed to do it. We as a family became the editorial team. We came together at our kitchen table with our laptops out, we made tea, ate, went swimming (because we worked in the summer a lot), came back to the work, cooked, slept, discussed.

The family was a collective, but then we asked friends for support. A situative knowledge of people was necessary, with a sensitivity to racism. They needed to be friends to understand the project.

NP: I was struck by the annotations in the translation, how certain words defy translation?

CBM: The translation was such an interesting process. Some words we did not translate like the Turkish “Chai” for tea. We added the annotations, because in Turkish a lot of words are gender-neutral, like “friend.” It is not clear if she means a man or a woman or a non-binary person, or another person. We realized we could not translate her words one-to-one. We needed to translate it so people could understand the German and the Turkish language. Sometimes she invented comparisons or metaphors that do not exist in either language. “Unheimlich Glücklich” (unbelievably happy) or “Mein Name ist Ausländer” (My name is foreigner) are very strong in German. There was an annotation in Turkish because in German “heimlich” has the word “home” in it. She crossed out certain words like “homeland” and then she wrote “people” instead. I think she was trying to say: home is a construct. We kept both because we did not want to censor her. Her poems are a historic document of her and our time.

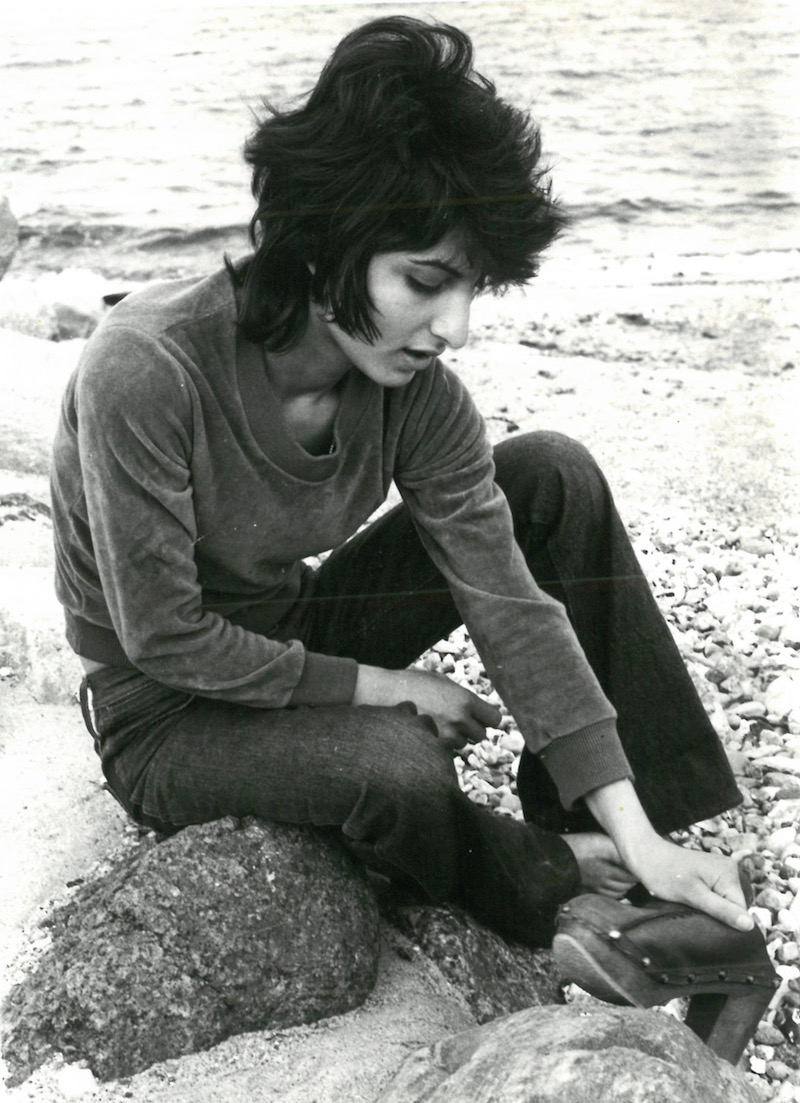

Cana Bilir Meier: ‘Semra Ertan,’ 2013, HD Video, 16:9, Colour, B/W, Sound, 7:30 min. // Courtesy of Cana Bilir-Meier

NP: How did the publishers react?

CBM: Nine years ago, I wrote the first e-mail to a publishing house in Germany but we were not prepared. We had some bad experiences pitching it to large publishing houses. They questioned the Turkish translation and only wanted a German version. This would not do her justice. They did not accept her poetry as it was, they wanted to have a book about “migrant literature.” They said otherwise no one would buy it. One of the biggest publishing houses called her poems “not reflected enough,” stating that they only publish “high culture literature.” Some institutions want to take part in the trend of using diverse authors, but as soon as someone places a demand on them, it is too much. One of her poems was printed in the same publishing house without our knowledge or consent.

Semra Ertan wrote about many topics: love, anger, happiness, death, about being a daughter, and a worker. That is why we were so grateful to work with the edition assemblage. They gave us total freedom of expression.

NP: Semra Ertan is a very complex, strong woman, worker, writer and traveler.

CBM: She takes on so many roles in her poems, she even writes: “I am not a professional poet.” In my opinion, she questions who has the right to speak and who is allowed to name themselves a poet and who is seen. What she means is: “I am not a canonized author, I am not accepted, I am excluded.” She says, “I will live through writing” (Mein Leben wird schreibend verlaufen). She says: “My page is inexperienced, my hand-writing is inexperienced, I am an inexperienced poet.” She started reflecting and writing at age 15!

NP: As an artist, you have devoted parts of your body of work to her. How is your growth as an artist connected to this book?

CBM: The book reflects on many issues I work on. Her poetry belongs to my body, it is like a hand. I made a short film about Semra Ertan in my first semester at art school, about the media and archival footage and, since then, it has only been a matter of time before we would publish the book. I see it as a responsibility to publish her book. I have the privilege, I have the education, I am now in the position I wish that she could have been in. My parents were the first to study in their families and they provided me with a very high education, I am so grateful to them for their support.

NP: Now that this first book is here, does it feel like some healing has taken place?

CBM: Yes, this book keeps her ideas alive. We knew that she wanted this and now her wish came true, and this is a huge relief. The most beautiful thing is that people will read it. So, on the one side, it was really hard to find support in the publishing world, and, on the other, there are so many people who want to read her words. There is an ambivalence in the societal majority that thinks they are the majority because they are in power. But there is a mass of people—like in Munich, for example, 42% have a diverse cultural background—who speak more than one language, other than German. How can it be that it seems they are the minority? That’s why I think the word “Dominanzgesellschaft” (dominant society) suits the situation better. The dominant define the present. We need a more transformative change in society. I think it is possible.

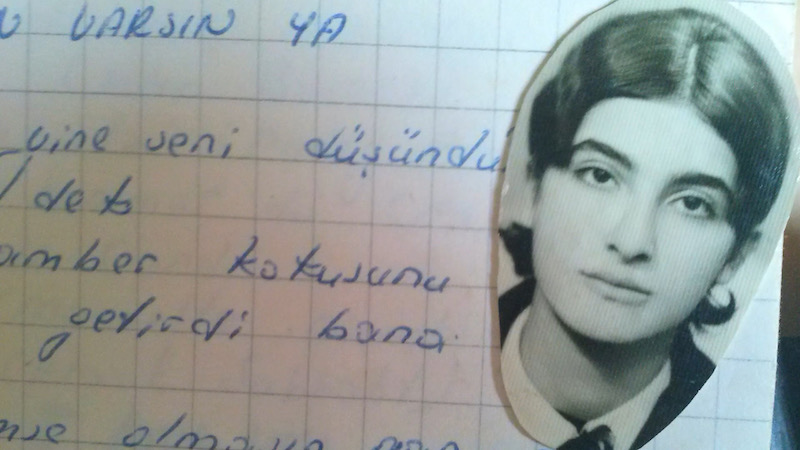

Semra Ertan, author portrait // Courtesy of the Bilir-Meier Archive

NP: A lot has been written about this book in the German-speaking media. How has it been celebrated?

CBM: We appreciate that so many people want to write about this book, but we are surprised by the focus on her political side. Her activism was more than just demonstrating. Poetry was her activism, too. She had joy and writing was her tool to deconstruct reality. We made this book to focus on her writing and all the other themes she covered. We wish journalists would focus on this, too. Some journalists turn her into a victim by asking why she killed herself. It is a form of racism to question the person who suffers from discrimination. We are not interested in this storytelling, we did not intend to write her biography. We wanted to publish her poems. She suffered from the structural prejudice so much, but she never stopped writing. Semra wrote: “I will share my scriptures generously.”

NP: There is so much hope in this book. What can we learn form Semra today?

CBM: Poetry can be read a hundred times and every time it will teach you something new. It is like a rhythm. It is life. It is knowledge. This book can travel with you. She talks about timeless issues: discrimination, racism, classism, sexism, ableism. I think there are many people who have had the same experiences and who demand to read this book. We recognize how many writers are departed, who never got published and just disappeared. It is an unfortunate privilege.

She is an activist, she is a woman, she is a traveler.

She writes:

“I want to live,

how I wish,

painless,

without worries,

I want to love,

be loved,

as my heart dreams,

with a pure heart…”

She died too young and it is devastating that she killed herself. She has so many different sides, showing us empowering perspectives for looking at life. The scholar Gloria Anzaldua writes in her book ‘Borderlands – The New Mestiza,’ that visible borders are made by humans and they separate us, and then there are the invisible borders—like the problematic idea of the binary of gender, nationalism, or racism—which divide humans in groups. She suggests we must tell diverse and multiple stories of identities. That is why we don’t tell one single story of Semra Ertan. The poems are her own story.

This book is a bridge for life to cross these borders. The poems are, for me, a tool for life, to critique, to love, to be happy. Today, teachers are using her poems in classrooms and activists are quoting her at demonstrations.

This article is part of our feature topic of ‘Ritual.’ To read more from this topic, click here.