by Noushin Afzali // June 4, 2021

In an artistic career ranging from video, film, photography and performance to embroidery and text, Dante Buu’s central issues are love, resistance and intimacy. Born in Montenegro, Buu is currently an artist-in-residence at Künstlerhaus Bethanien. His work blurs the boundaries between the private and the public sphere and addresses the sociocultural alienation present in our societies. In an intimate quest of resistance and subversion, Buu questions and challenges gender roles and stereotypes that are set up by mechanisms of power. As a storyteller and performer, he intertwines his own life story with the untold stories of others and uses his artistic practice as a vehicle for resistance against marginalisation and invisibility of minority groups. His upcoming exhibition ‘thigh high’ at Künstlerhaus Bethanien was an excuse for us to sit down and discuss notions of intimacy, resistance, and identity inherent in his work.

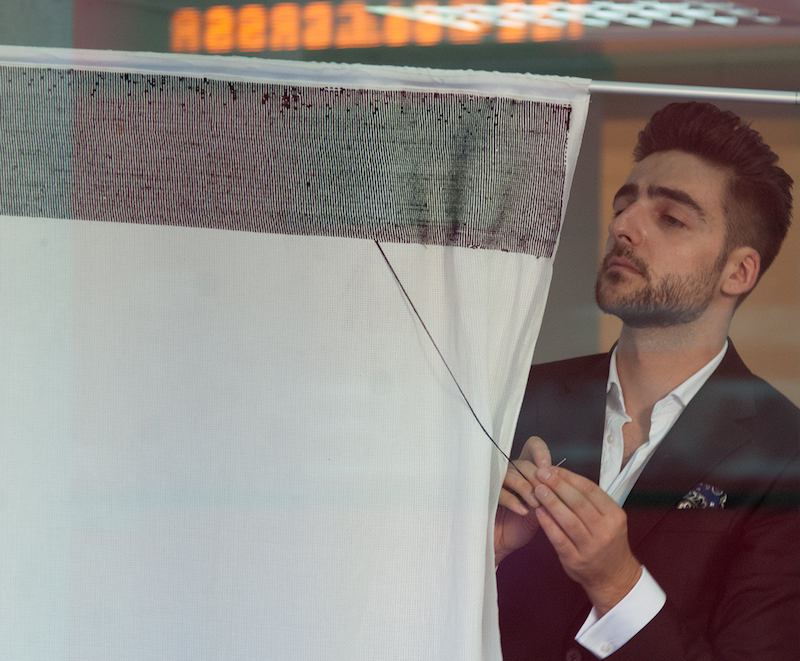

Dante Buu: ‘A Portrait of My Parents / Summer (Fifth Season),’ 2014, performance at Gallery Java (Sarajevo), duration: 8 hours // Photo by Aleksandar Kordić

Noushin Afzali: You once said in an interview that your resistance against oppression is rooted in intimacy, encounters with other people and the stories we tell. With the outbreak of the pandemic, we’ve all had to rethink and redefine our understanding of “intimacy” and its manifestations in our day to day life. How has the pandemic influenced the performativity of intimacy in your artistic work?

Dante Buu: Before the pandemic, my practice was bound to my personal experiences intertwined with encounters with people, stories they tell…especially the untold stories. In my opinion, the personal is always political and the political is always personal. Intimacy is also a very political thing because on so many levels our intimate space is controlled and supervised. In many cultures, if not in all, it’s expected to be kept hidden. When you come from the LGBTQ+ community, it is a huge issue to show affection and be intimate with your partner in most parts of the world; though some societies are not kind even to the heterosexual couples when it comes to public affection. When the pandemic struck, in a way, all of us were left with ourselves, alone with our intimacy. And whether we wanted to or not, we had to take a deep look at ourselves. My blink-less gaze in the eyes of my intimacy reaffirmed my belief that we are all equal and, different as my previous conviction, that we are, in our intimacy, pretty much alike. We all suffer from the same pain, we want the same things; we need to love and resist to thrive and live.

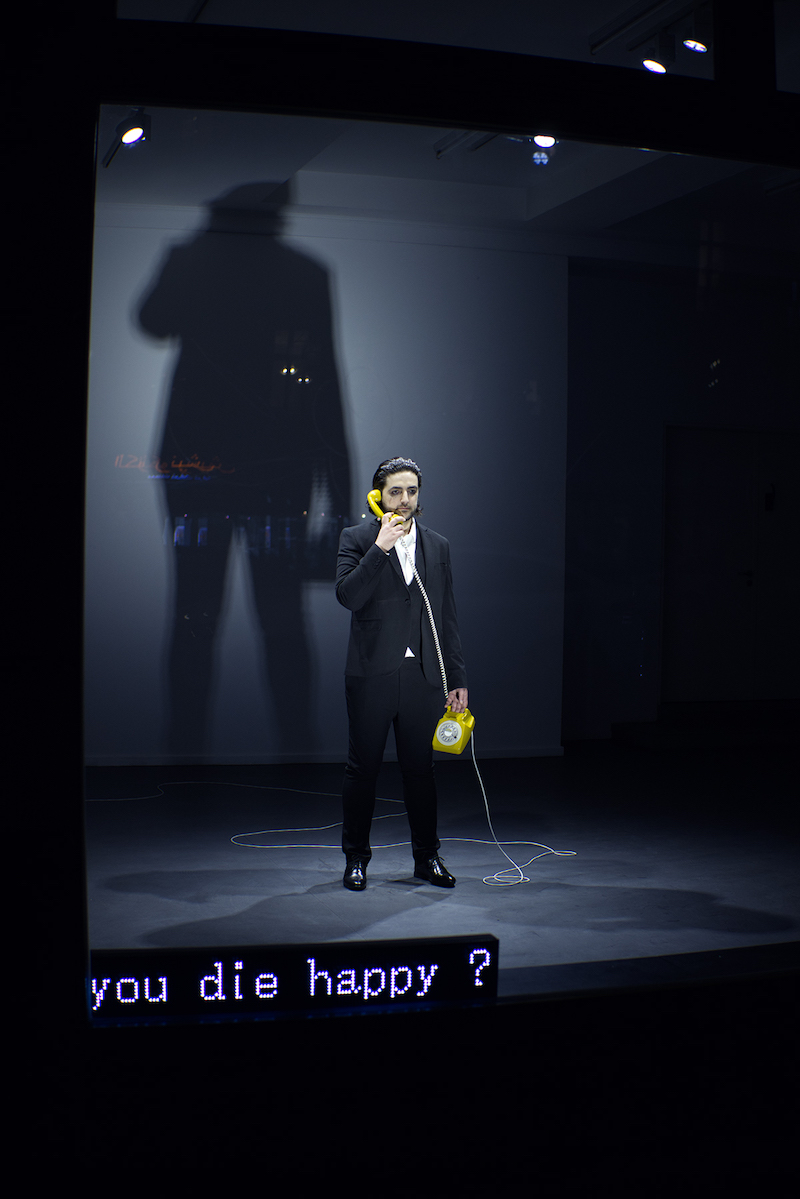

Dante Buu: ‘and you—do you die happy?,’ 2021, performance at Künstlerhaus Bethanien Berlin, Duration: 8 days, 4 hours per day // Photo by Bastian Hopfgarten

NA: In your recent durational performance ‘and you—do you die happy?’ in the windows of KB, what ideas were you trying to get across to passers-by, with regard to the blurred boundaries between private and public? What reactions did you receive?

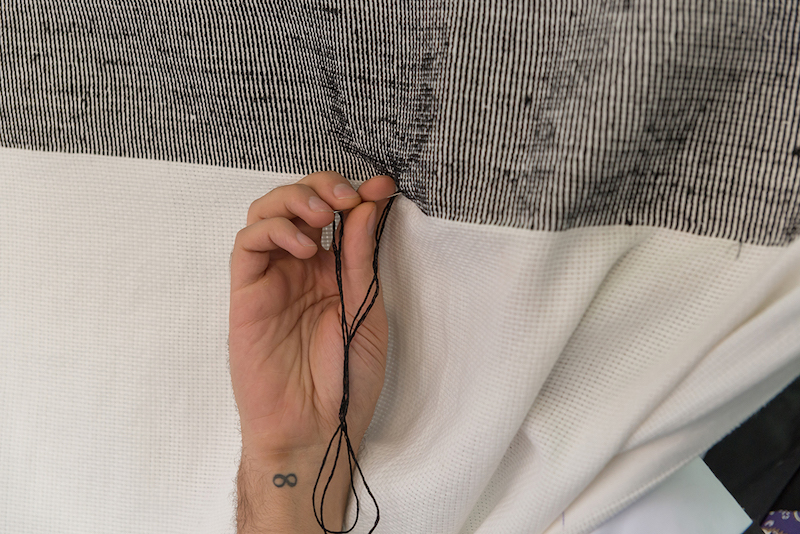

DB: I did my first long durational performance titled ‘A Portrait of my Parents / Summer’ in Sarajevo in 2014. The summer that moved me towards this piece was one of the most difficult summers in my life. My dad fell down from a sweet cherry tree and broke his spine. My first encounter with this terrible thing that had happened was in the hospital room where I saw my mother sitting at the foot of my father’s bed waiting for him to wake up after surgery. It was one of those times or moments in which you realise where the border is, beyond which you are powerless. I could only stand and observe… waiting. The same waiting that I shared with my mum, that protracted and endless waiting for a miracle to come. And, there I was in a hospital room, standing and looking at the two people who created me, unable to do anything to help them. I was reflecting in them as they reflected in me, so I took a needle, a black silken thread and a white cross stitching grid. I started to create them with embroidery. Between the ‘A Portrait of my Parents / Summer’ and ‘and you—do you die happy?’ a lifetime, or rather 17 lifetimes happened [laughs], and so much of me and so much of the world has changed.

‘and you—do you die happy?’ is actually the first artwork that I did publicly during the pandemic, so this space that I shared with the audience was compromised because of the social distancing. It was very interesting to have this experience, for eight days, four hours a day I stood completely still in the window of KB, and was so exposed, so seen. But, on the other hand: was it me? I was performing, I had a costume, a prop (the telephone) and the mascara-stained tears. I went back to connecting with audiences through a long-durational performance as a staged image of myself that haunts me. And the reactions were very different. It went from extreme love, people coming and kissing the window, which was so beautiful. There was this golden-haired girl, I think I will never forget her. She came very close to the window and she said to me, “Blink twice if you want me to save you.” It felt like so much love, care and support. But, from the other side, there was so much violence. People were very violent in terms of hitting the glass, throwing things at it. And, of course, it was mostly male passersby. I don’t want to sound stereotypical, but most of the love came from women. And, of course, there were also some men who were very affectionate, one might say very seductive towards me. After a certain time of standing motionless, your body starts to ache terribly. But that energy, it’s something that I have never felt before. And, way more interesting than the pain, is to see how people react to a performance. What does it do for them?

Dante Buu: ‘and you—do you die happy?,’ 2021, performance at Künstlerhaus Bethanien Berlin, Duration: 8 days, 4 hours per day // Photo by Bastian Hopfgarten

NA: When researching about your work, one encounters this statement time and again: “the only artist from a Muslim background to ever come out as gay publicly in the Balkans.” Apart from the significance of sexual orientation in forming our identities in a binary world, to what extent do the political implications of this coming out matter in your artistic oeuvre?

DB: I come from Rožaje, Montenegro. I was born into a Muslim family and I’m gay. Muslims are a minority in Montenegro. So, without doing anything, your being, just by its existence, religion or its sexual identity, is very political. In countries that are nationalistic and homophobic, that is a huge problem. Personally, I am a walking target for any piece of shit who is convinced by the shitty society in its righteousness, to harass me and threaten my life. “The only artist from a Muslim background to ever come out as gay publicly in the Balkans”—sounds pretty unbelievable now in 2021, right?

One of my first artworks was, ‘Male to Male Passport’ (2013). It is a text installation that says: “I fuck with foreign men because from where I come no one is gay.” It is a very politically-charged work about, as I said before, being so exposed and my body being so political against my will. When I was growing up, I had no one to relate to, I was surrounded by heterosexual couples. I think it’s important that people who are, let’s say, public personalities or public figures, that they speak out, because the fact that I’m the only one who said it says a lot about the situation. And it created so many problems for me. It created so much heartache, suffering, death threats and serious professional complications; in a way, through everything that I am going through, I can understand why other people are silent. But, in the end, I did nothing wrong and there is nothing wrong with me and there is nothing wrong with anyone who is different. And when it comes to work, for me, it’s always very important to have this activist stance because art is about speaking out, resistance; touching upon different issues and different problems.

Dante Buu: ‘A Portrait of My Parents / Summer (Fifth Season),’ 2014, Photo documentation of performance at Gallery Java (Sarajevo), Duration: 8 hours // Photo by Velija Hasanbegović

NA: Your artistic career spans from embroidery and text to video, film, photography and performance. By integrating embroidery in your work, you have knowingly entered a domain that has traditionally been dominated by women. Can you elaborate a bit about the importance of this artistic impression in your work and its relation to being raised in a household of women?

DB: No one ever showed me how to do embroidery, as “boys are not supposed to embroider.” I learned only by watching my grandmother, my aunts and my mother do it. Embroidery is the most intimate of my art, as I spend most of my time creating it. And I’m so slow when it comes to embroidery. The least amount of time that I spent on an embroidery was three months, and the longest was four years. So, it takes a lot of time, a lot of working hours, a lot of me in different emotional states.

For my upcoming show ‘thigh high’ at Künstlerhaus Bethanien, it will be the first time that I show my embroideries. I’ve never shown them before because I’ve been very shy about them and terrified that they are going to be sold, as they are so intimate and unique. But, to every thing there is a season and, as I said before, I have changed and now I am ready to show them. Of course, I did live embroidery as part of my performances, but the ones that are going to be shown now, which are abstract and sculptural, which are done very intuitively, where I just intuitively take a colour and embroider the shape in that moment how I feel, it’s something so deep and personal and unconstrained in its bareness. I know it’s a female domain, but that’s also just a normative rule. It’s just some model of thinking that is forced upon us. I love embroidery.

Dante Buu: ‘If you wanna fuck me, you don’t have to pretend it’s for art,’ 2018, Fine art inkjet print, 116 x 207 cm, unframed // Courtesy of the artist

NA: The significance of space is another motif that is very central to your work. Your works are understood by an incessant inquiry into the increasingly blurred boundaries between the private and public realm. This understanding varies from place to place. Tell us a bit about your experience of living and working in Berlin.

DB: Berlin is my big love. For me, when I’m in Berlin, I feel free. I just like how huge it is. I love these wide-open streets. There’s nowhere like here, you can breathe. Being so overexposed, for all the wrong reasons, for so much of my life, I just love going down the street and no one is looking at me. That’s so beautiful; this space for anonymity. I love that I don’t feel forced to do anything here, I don’t feel that I need to behave in a certain way. You can see a lot of intimacy publicly in Berlin.

There are these beautiful and freeing spaces geographically, there are these spaces in art too and they too can be dark and difficult. When you come from an underprivileged position, there are a lot of institutions and people who are more than willing to abuse and use you and your precarious circumstances. This happened to me a lot, most recently with the Mediterranea 19 by BJCEM in San Marino (2021), from which I withdrew very publicly via an Instagram story because they were ignoring my emails on the production and installation of my work to the day before the opening, and by doing so I was supposed to work on Eid. I just will not stand for such blunt disrespect. Personally, for me there is no difference between the homophobes that threaten my life and an arrogant curator, for example: both of them are just a product of an oppressive society that wants to exercise its power. But where there is power, there is resistance.

‘If you want to fuck me, you don’t have to pretend it’s for art’ is an artwork that I did in 2018, for an exhibition at < rotor > center for contemporary art in Graz. And this work deals explicitly with the precarious circumstances of artists and the inevitable abuse that we are facing on so many levels and the need to speak out and call out those who harm us, to stand defiant and bold.

This article is part of our feature topic of ‘Intimacy.’ To read more from this topic, click here.

Exhibition Info

Künstlerhaus Bethanien

Dante Buu: ‘thigh high’

Exhibition: June 11–July 11, 2021

bethanien.de

Kottbusser Str. 10/d, 10999 Berlin, click here for map