by Denisa Tomkova // June 18, 2021

Roma corporeality, non-binary spaces, gender issues, the relationship between intimacy and technology, as well as the need for inclusive art institutions, are all topics addressed in Robert Gabris’ artistic practice. Gabris is a Slovak artist living and working in Vienna. In his autobiographical work, Gabris addresses identity and its intersectional layers, as someone who belongs to both the Roma ethnic group and to the queer community. In 2020, Gabris was selected to spend two months at the Villa Romana residency in Florence, where he developed his project ‘Insectopia,’ which focuses on the human body and identity in a state of constant change. Gabris is also one of the 2021 selected finalists of the prestigious Czech art award, the Jindřich Chalupecký Award. As exemplified recently in other international art awards like the 2019 Turner Prize, Gabris and the other selected finalists chose collaboration over the competition, and decided not to accept a single winner. We spoke to Gabris about his most recent project ‘ERROR,’ which is a work-in-progress for the 2021 Jindřich Chalupecký Award exhibition, which will open this autumn at the Moravian Gallery in Brno. We talked about safe space, intimacy and technology: in ‘ERROR,’ the artist met his project’s participants through online dating apps. Does technology have a potential to provide emancipatory powers, especially for marginalized and queer communities? What are inclusive art institutions and how can they be shaped from below and conceptualized by a minority group itself?

Portrait of Robert Gabris

Denisa Tomkova: Please tell us about your new project ‘ERROR. Roma corporeality and its non-binary spaces,’ which you are currently preparing for the Jindřich Chalupecký Award exhibition. Why did you decide to address this particular topic in your new project?

Robert Gabris: I went to an artist residency program in Kosice and opened a dating app there to network and have fun. To my surprise, I met many Roma queer people there. These people often consider their sexuality taboo, because they are not allowed to express it freely. I couldn’t hold back my enthusiasm, I met many of them and decided to work with this topic. Why? Because it is simply existentially necessary, acute, to open and discuss critical discourses of gender issues, patriarchy, white supremacy and systematic marginalization of excluded groups in Slovakia. Our country does not know us, is afraid of us, or even worse, is apathetic towards our problems and needs. I have two strategies: firstly, I want to connect the community and create a space where we feel safe and heal ourselves. Secondly, I want to hold up a mirror of unacceptable oppression towards us to those who are ignorant of it in our society.

Robert Gabris: ‘You Will Never Belong Into My Space,’ 2020, Vienna // Photo by Theodor Moise

DT: In your artist’s text you refer to Legacy Russell’s book ‘Glitch Feminism: A Manifesto.’ Russell, through the concept of cyberfeminism, proposes that there is a relationship between gender, technology and identity. Similarly, you met your project’s participants through online dating apps. Can you please tell me more about the potential of technology to provide emancipatory powers, especially for excluded and queer communities, in particular in the east of Slovakia where you conducted your project?

RG: This topic is so complex and not one-sided. On the one hand, technology (dating apps) are helpful to connect, I don’t know how else I would meet these people in real life. In Eastern Slovakia, there are no opportunities for us, queers, to meet. We just don’t have any resources. Most of these people live isolated, in ghettos, or on the margins of society. On the other hand, these bodies are exploited, physically violated and exploited in online and offline spaces because these apps are also dominated by white people. An online space simply does not change what is inside these societies. Racism, sexism (exoticization of Roma bodies), apathy or just general hatred towards us.

DT: During the recent COVID-pandemic, how much could technology, like these apps, provide the needed space for intimacy and connection? What was your personal experience?

RG: I consider myself a digital native person and, of course, I experience intimacy online as well as offline. I communicate with my phone and computer every day, they are the most important tools for my work. Fortunately, I live in a happy intimate relationship with my husband and that helped us to beat the pandemic. In my work, I missed the real dates and meetings very much. So I focused more on my work at home, I read what I had neglected before, I was in nature a lot, to renegotiate my not-so-easy relationship with her.

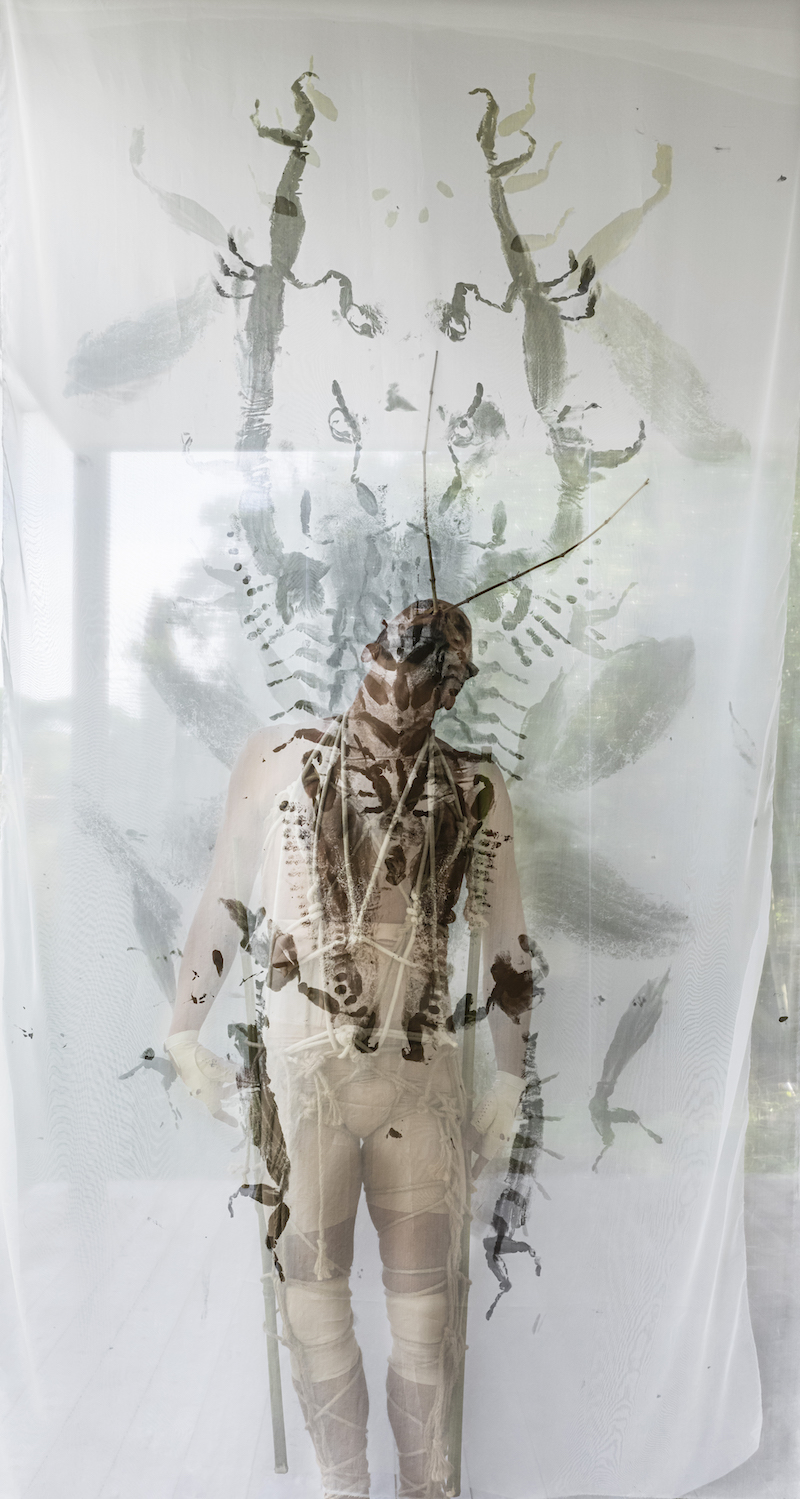

Robert Gabris: ‘Insectopia,’ 2020, performance in Florence // Photo by Ela Bialokowa, Okno Studio

DT: Your project has a conceptual overlap from the topic of Roma corporeality and non-binary spaces to the larger theme of inclusive art institutions. Could you expand on your demand for inclusive institutions from below, where the space is shaped and conceptualized by a minority group itself? Why is this practice important in your view?

RG: This is a simple, long overdue demand for institutions that claim to be inclusive and open to us. We are only promoting what has not been given to us until now, but which also absolutely belongs to us—restitution and justice. If the political situation in our country is to change, responsible institutions must allow us to participate in progressive change. Or rather, they must provide us with all the resources we need to do the necessary work ourselves. We want to determine for ourselves who we are. We want to determine for ourselves how we are looked at and talked about. We need visible sovereignty to be able to emancipate ourselves. We need strategies for a new foundation to be able to build a house that is only ours. We are not guests in this country, we are a legitimate part of these systems, we demand the freedom to determine our own presence.

We want to free ourselves from your normative constructions, conceived on hate and repression. The ones you have built for us, but without us, under our feet, are full of holes, lies and acutely crashing. It’s time to open your blind eyes, dare to step back, stay quiet, turn around and listen to what we have to say.

Robert Gabris: ‘Insectopia,’ 2020, performance in Florence // Photo by Ela Bialokowa, Okno Studio

DT: Last year, during your Villa Romana residency in Italy, you created your work ‘Insectopia,’ which focuses on the human body and identity in a state of constant change. Could you tell me more about this work and your inspiration for it?

RG: ‘Insectopia’ is a metamorphosis of a human being who has become an insect, paralyzed, mute and motionless. He became an exhibit in the ethnological museum, imprisoned and nailed in a glass cube. The ethnological museum is trying to decolonize Europe, alongside existing collections, without restitution and the necessary educational work they are supposed to do. Instead, they use contemporary artistic positions to justify their own legacy. I got an invitation to exhibit in such a museum, so I sent them a print of my anus and genitals, because I compare this kind of anthropology to criminology (fingerprints). I wrote in my concept: My body and identity are in constant motion. This is the only thing I can find after years of searching for a reference to the topic of Roma resistance. My identity has no significant ethnological attributes and I distance myself from previous anthropological research.

I don’t emigrate, I don’t assimilate, I don’t integrate. If you want to identify my fingerprints, you have to go through my ‘Insectopia.’

This article is part of our feature topic of ‘Intimacy.’ To read more from this topic, click here.