by Erin Honeycutt // July 6, 2021

When I hear dulsmál I think of dulspeki, which is the Icelandic word for “mysticism.” It signifies a mystery, or, under these circumstances a “hidden case,” like a hidden pregnancy. When María Dalberg was studying history in Reykjavík a decade ago, she came across these “hidden cases” written down in Icelandic as part of the Icelandic court system, while some of the cases were taken to the highest court in Denmark. Unmarried women were obligated to inform the authorities in the event of pregnancy and given lashings and fines for their transgression. A stillborn was assumed murdered by the mother, which was always her fault unless she could give proof. Often, the child was born lifeless, and those found “guilty” were given harsh punishment. In these court statements, accused women give voice to their experiences. While dulsmál is to hide a pregnancy, it is not murder; it is the act of keeping the whole truth a secret.

María Dalberg: ‘Uncontainable Truth,’ 2021, video still // Courtesy of the artist

In Dalberg’s exhibition, a video installation shows two screens: on one screen, five women draped in red clothing walk along a beach, each representing the women whose voices are used for the multi-vocal poem recited by the narrator. In a parallel video, a woman’s mouth with red lipstick, close up, recites a poem in Icelandic. It appears as though she is reciting the poem to anyone who will listen—perhaps the sun, the storm, the surf, the rocks, the wind? A strand of dark hair is in her mouth as she speaks, an unkempt disobedience that speaks volumes.

The women in the video perform the movements of labor modeled after descriptions of how women washed clothes in Iceland during this time period. In their labor, the crashing waves and howling wind can be heard behind them while their voices are silent. It is as though the surrounding landscape’s power speaks through them. Dalberg has arranged the scene to the buzzing sound of trumpets (by the composer Áki Ásgeirsson) that seem to give off an audible aura of pressure to the voices that have no voice.

María Dalberg: ‘Uncontainable Truth,’ 2021, video still // Courtesy of the artist

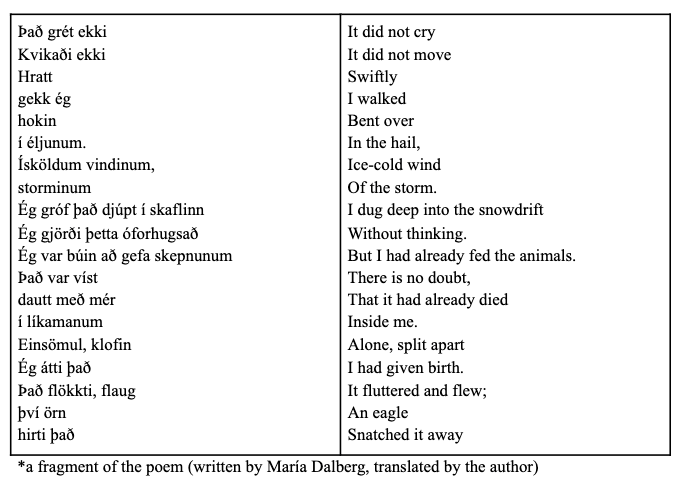

Dómabækur (Judgement Books) were the manuscripts in which these court cases were handwritten by the sheriffs in each county. From 1700 onwards, Iceland used Norwegian laws for dulsmál whereas, before 1700, they used Danish laws for the majority of cases. The accounts are found in Dómabækur and also in the printed archives of the Annals 1400–1800 and Landsyfirréttadómar. The poem recited in the work, written by Dalberg, is a collage of archived court statements found in these three sources by working-class women in Iceland in the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. A labor system was used in Iceland at the time, called vistarband, requiring landless people to work on a farm if they did not own land, a system that became more strict during the 17th and 18th centuries.

The translation of a court document into a poem is a feat. While recognizing that the fundamental differences between these activities cannot be ignored—that a court document from the 18th century is inevitably a different written text than a performed poem, that a written poem cannot shake some aspect of textual fiction, and that poetic making and biological making are, of course, totally disparate—this video work dwells in the intersection between kinds of labour, both poetic and biological.

María Dalberg: ‘Uncontainable Truth,’ 2021, installation view, Künstlerhaus Bethanien // Photo by David Brandt

The act of giving voice to the unheard, of giving breath to an archive, combined with Dalberg’s use of non-human sound in the video pushed me towards situating this transhistorical work within the poetics of Alice Notley (1945), an American poet associated with the second-generation New York School of poets, who has written extensively on women’s labour, grief, the poetic voice and the cultural importance of disobedience in many cross-genre volumes.

Reading closely into these court documents, as Dalberg has done, has produced new forms, as a way to see both poetic and reproductive labor that is so often evacuated from poetry criticism. The work of Alice Notley provides a nuanced model for conceptualizing gendered reproductive labor and the authoritative system that has held it. In Dalberg’s video, the women are performing women’s labour; work involves gender, around which is a frustrating discourse beyond the domain of poetics. This work is often associated with battles of bygone feminists movements, which are still very present today. In the Icelandic context, it is still very hard to prove an act of rape and women are currently stepping forward, after having been silenced, in their own #metoo movement.

The riddle of dulsmál can be placed in a curious dynamic when considering the work of Alice Notley, whose insistence on presenting the pregnant state without metaphor represents an engagement with poetic representations of pregnancy, using a mimicry of figuration that presents women’s reproductive labor as the subject of her poems. Notley’s resistance to metaphor engages prior metaphorical pregnancies that relate gestation to inspiration, a trope across genres. The dulsmál is a kind of riddle that the women tell to get out of punishment.

In Dalberg’s recitation of the poem of amalgamated voices, it is registered that the voice is arriving from an object that was once a voice. The poet as an object and language as an object gives “objectivity” to the poem through breath, across time. Dalberg’s speech gives the verse a solidity, coming to terms with the mysterious way that poetics enact an experience, connecting the writer within the weave of the geological, human and literary history in which their work is arriving. Notley’s feminist epic from 1992, ‘The Descent of Alette,’ discovers a woman’s voice that encompasses a story existing on many levels, both conscious and unconscious, while always being situated in the present moment in which it is read. The choice of presenting the epic poem entirely inside quotation-marks pushes the reader towards realizing the surreal poem as a journey through the vocalized and an entrance of private language into the public domain:

“Then,” “as I swam,” “the others I contained—” “my companions

from the subway—” “weightlessly” “emerged from me,” “looking

shadow-like,” “& quickly” “solid-bodied” “began to swim with me”

“I never really” “saw their faces” “We swam quietly,” “concentrating,”

María Dalberg: ‘Uncontainable Truth,’ 2021, installation view, Künstlerhaus Bethanien // Photo by David Brandt

Dalberg’s manifestation of transhistorical women’s voices brings tension between the individual voice and the public function of voice as being “quotable.” Just as the women’s voices were recorded in court documents, bodily intimacy was concretized in the staid halls of democracy. The video work turns around again by returning the private moment to the viewer. Dalberg’s poem is also a fragment, as well as a fragment of a reality in which a narrative style has been used to mask the materiality of language. The narrative is as elusive as the justification that these women receive for their plight: without a voice. As a narrative strategy, Dalberg’s poem makes their experience visible, while connecting her voice to the fact that there is no rational logic to narrative they’re experiencing.

Like Notley, Dalberg imagines a poetry in which the memory of personal and collective injustices are presented on one screen in their separate representative bodies and, on another screen, in a collective, unified poetic expression bound by exasperation, binding the personal and the political through the channeled voice. The voice makes clear the visibility of stories and voices that have been marginalized as unreal, “uncontainable” and therefore immeasurable. The poetics of immeasurability in this context relates the fate of one to the fate of many. The lines themselves explore the confusion, the anger, the exasperation and the awe of labour. This labour has been given a voice centuries later, bringing a common agency to the silent voices that became an archive. Through the creation of a poetics of disobedience, the dulsmál can be read as a riddle for the state to decipher.

This article is part of our feature topic of ‘Poetics.’ To read more from this topic, click here.

Artist Info

Exhibition Info

Künstlerhaus Bethanien

María Dalberg: ‘Uncontainable Truth’

Exhibition: June 11–July 11, 2021

bethanien.de

Kottbusser Str. 10/d, 10999 Berlin, click here for map