by Noushin Afzali, studio photos by Ériver Hijano // July 13, 2021

As a graduate of the Computational Art/Generative Art program at the University of Arts Berlin, Petja Ivanova felt a deep dissatisfaction and frustration with the academic and scientific method prevalent in her fields, not to mention its male-dominated environment. To combat this state of affairs, she infused her artistic practice with another dimension: her aim is to promote the “poetic method” as a counterbalance to the “scientific method,” which she views as the presiding mode in a capitalist, imperialist and patriarchal society. In her intersectional feminist and trans-disciplinary practice, Ivanova combines biology and computation with spirituality and poetics. By incorporating electronics and sensors with plants, microorganisms, insects and bacteria, Ivanova wants to free herself from the dichotomous chasm between what is considered natural and what is seen as man-made and technological. Her practice is centred around a non-linear, mythological, non-quantifiable approach that strives to rid itself of the simple causalities in quantification.

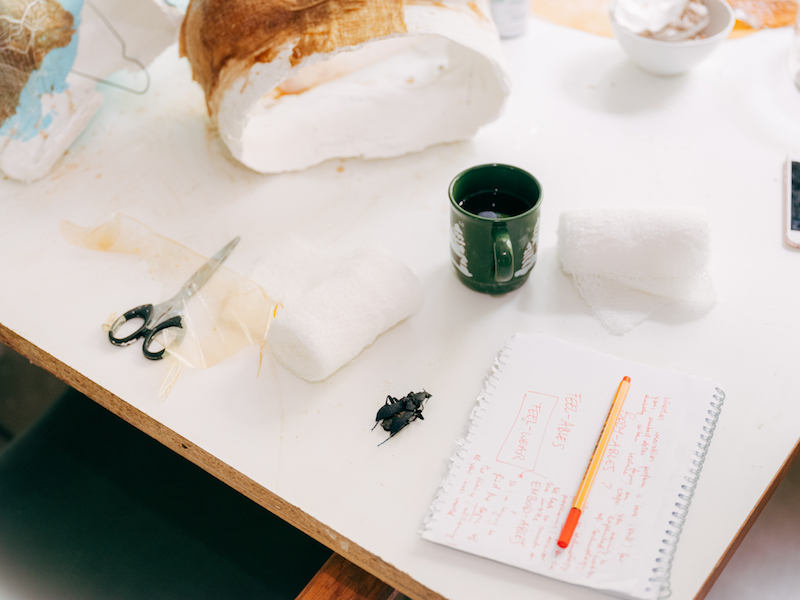

The Berlin-based Bulgarian artist welcomed us warmly in her small studio in Kreuzberg and took us through a journey of her artistic career, filled with insects, “feelables” and strange smells. On this summery day in July, the studio—which is located in the backyard of a building—is filled with sunlight. Ivanova’s long desk overlooks the tall, green trees of the yard. Entering the studio, a strong acidic smell pervades over the whole space. Her desk is filled with insects, bandages, and bowls filled with plum vinegar.

Ivanova’s most recent project consists of using chitosan in powder form to make wound healing bandages. Chitosan, a linear polysaccharide, is made by treating the exoskeleton of shrimp and other crustaceans. As a natural biodegradable biopolymer, chitosan is used in biomedicine in bandages to reduce bleeding and as an antibacterial agent. Ivanova’s innovation is using insect exoskeletons to extract chitosan. The insects go through a “metamorphosis, leaving their old bodies behind.” By using chitosan and vinegar, Ivanova makes her own DIY healing bandages, which she uses afterwards in her sculptures, giving them “an insect-y aura” and also dealing with an age-old tradition of wound healing.

Ivanova is also fascinated by the relationship between fermentation and witch knowledge. Fermentation, as “the core technology for social evolution”—to use Ivanova’s own words—is an ancient practice. This experiment is then an attempt to “create a world around this lost knowledge.”

Having studied Computational Art, doing research and consulting medical papers is nothing new for Ivanova. In fact, an extensive part of her time is dedicated to doing research, reading scientific papers and conducting experiments in the laboratory. What she finds problematic, however, is the linearity of computation. She believes that capitalism has transformed the essence of technology from the goal of saving lives to reducing all matter to sellable objects. In this way, “technology is seen as a prosthesis for replacing the skills one has.” Her aim, then, is to focus more on “emotional technology.”

Since the topic of the “poetic method” comes up time and again in Ivanova’s oeuvre, I asked her to elaborate on it more. She believes that “an epistemology of feelings” emerges when one reads poetry; when the linguistic elements connect to the feelings not only on the cognitive level, but also on the level of affect. Creating this other level is what Ivanova wishes to achieve with her practice.

She mentions ‘Manifesto for Cyborgs: Science, Technology, and Socialist Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century’,’ written by Donna Haraway in 1985. As a prominent feminist scholar in the field of science and technology studies, Haraway’s works criticize anthropocentrism and call for a rethinking of ethics with an emphasis on the power of nonhuman processes. In a similar vein, Ivanova explores the influence and intertwinement of our mental, social and environmental ecologies with a feminist focus. In her research, she is trying to understand “how my emotional and material ecology connect.” She balances her artistic passions with her interest in research with a part-time PhD position in Hamburg. This academic pursuit shows that Ivanova is not completely against the “scientific method.” But her skepticism about certain firmly held systems of knowledge brings a welcome critical eye to the discipline.

Ivanova runs the ‘Studio for Poetic Futures and Speculative Ecologies’ out of a little caravan in Berlin. By “poetic futures,” she means the idea of building institutions where emotions are as equally valued as efficiency or rationality. They are built on an intimate knowledge of the self and the environment and are pluriversal in a way that allows space for “currently marginalized knowledge forms.” As such, “poetic futures” will account for folklore, indigenous knowledge, spirituality and intuition. “Speculative ecology” is how Ivanova wishes to approach this poetic future-making. Inspired by Félix Guattari and his famous book ‘The Three Ecologies’ (1989), in which he discusses the three interacting and interdependent ecologies of mind, society, and environment, Ivanova believes that our mental and emotional ecologies are moulded after our environmental ecologies and that they transform through nature-culture processes. Organisms, especially insects, are, therefore, a source of metaphoric inspiration for her.

I’m drawn to a sculpture at the far left side of the room. Her recent exhibition ‘On frail ground,’ a dual show in May 2020 at Art Claims Impulse, was a testament to “the creation of an existential feeling; a feeling of fragility, of imminent collapse.” Set as a dialogue with the Romanian artist Mihai Grecu, Ivanova exhibited armour in ‘On frail ground,’ referencing sculptures moulded from the chests of her cis-male artist friends. The sculptures were made out of DIY chitosan wound healing bandages. Playing with the inherent ideologies of a patriarchal society, Ivanova drew attention to the problematic binary of male and female traits here. The armours were used as protection shields, but “metaphorically these second skins keep us from connecting with parts of ourselves and with one another due to the inherent psychological mechanisms in a patriarchal society.” A requisite for growing is, however, allowing oneself to be vulnerable. The metaphor of the armour is used here to show that by allowing oneself to be vulnerable and to be broken, one can actually embark on a healing journey.

As part of a residency in Italy in October of this year, Ivanova is collaborating with the musician Baal & Mortimer and the dancers Camilla Borud Strandhagen and Gabriella Forzelius. The dancers will perform while wearing smartwear designed by Ivanova. Ivanova rejects the term “wearables” and prefers to use the self-made term “feelables.” Wearables signify to her the term “owned by the tech world of self-optimization in order to fit into the current exploitative system.” “Feelables,” on the other hand, are more about embodying new qualities and learning from the body-mind-environment assemblage. This neologism points, once again, to her inclination towards the poetic and emotional dimensions of technology. For the performance, Ivanova is designing underwear equipped with a sensor that, once triggered, will start a fountain. In a playful twist, the artist explains that it’s supposed to “give the vagina a voice.”

Later this summer, Ivanova is also facilitating a workshop as part of her PhD research, hosted by The Witch Institute–a one-time symposium organized by the Department of Film and Media at Queen’s University in Ontario, Canada. The ‘Design Workshop for the Socioeconomic Membrane that Enfolds Her Casserole Dish’ will focus on how to design with magical consciousness and an intimate knowledge of one’s surroundings.

Leaving the studio, what resonates with me is the image of an armour sculpture inscribed with a 3D pen that Ivanova had displayed in a former exhibition. The inscribed quotation is taken from ‘The Will to Change’ by the feminist scholar bell hooks: “Cultures of domination rely on fear in order to separate.” By integrating a spiritual and poetic method in her practice, Ivanova aims to dismantle these cultural narratives and create a space where togetherness and pluriversality become the norms and not the exceptions.

This article is part of our feature topic of ‘Poetics.’ To read more from this topic, click here.