by Aoife Donnellan // July 27, 2021

Sarah J. Sloat’s poetic and artistic oeuvre focuses on bringing new and unpredictable connections between text and visual experience to light. Her practice consists of both textual and visual processes including erasure poetry, collage, drawing and a variety of other media. Sloat’s work transforms the pages of books into blank canvases, onto which she builds visual worlds. Through her use of erasure and collage, Sloat’s work coaxes original characters, situations and emotions out of pre-existing texts.

Sloat lives and works between Frankfurt and Barcelona. Her latest work ‘Hotel Almighty’ uses Stephen King’s book ‘Misery’ as its source text, from which Sloat creates a delicate and warm world of collage and text. Her visual intervention in the text allows the viewer to discover unfamiliar relationships between words amidst the uniform black typeface. Sloat’s practice investigates the navigation and reconfiguration of the voices and images of others to create personal, emotional and compelling work.

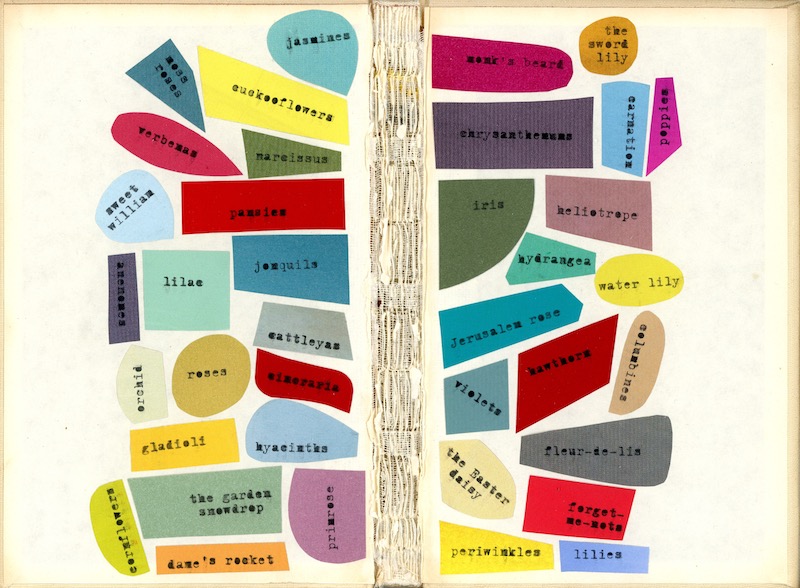

Sarah J. Sloat: ‘In the clouds this evening,’ a collage of the flowers included in Swann’s Way by Marcel Proust, previously published in Quarterly West // Courtesy of the author

Aoife Donnellan: Your latest work ‘Hotel Almighty’ uses Stephen King’s book ‘Misery’ as its primary text to create visually and linguistically stunning erasure/collage poetry. How important is the relationship between removal and creation in your work?

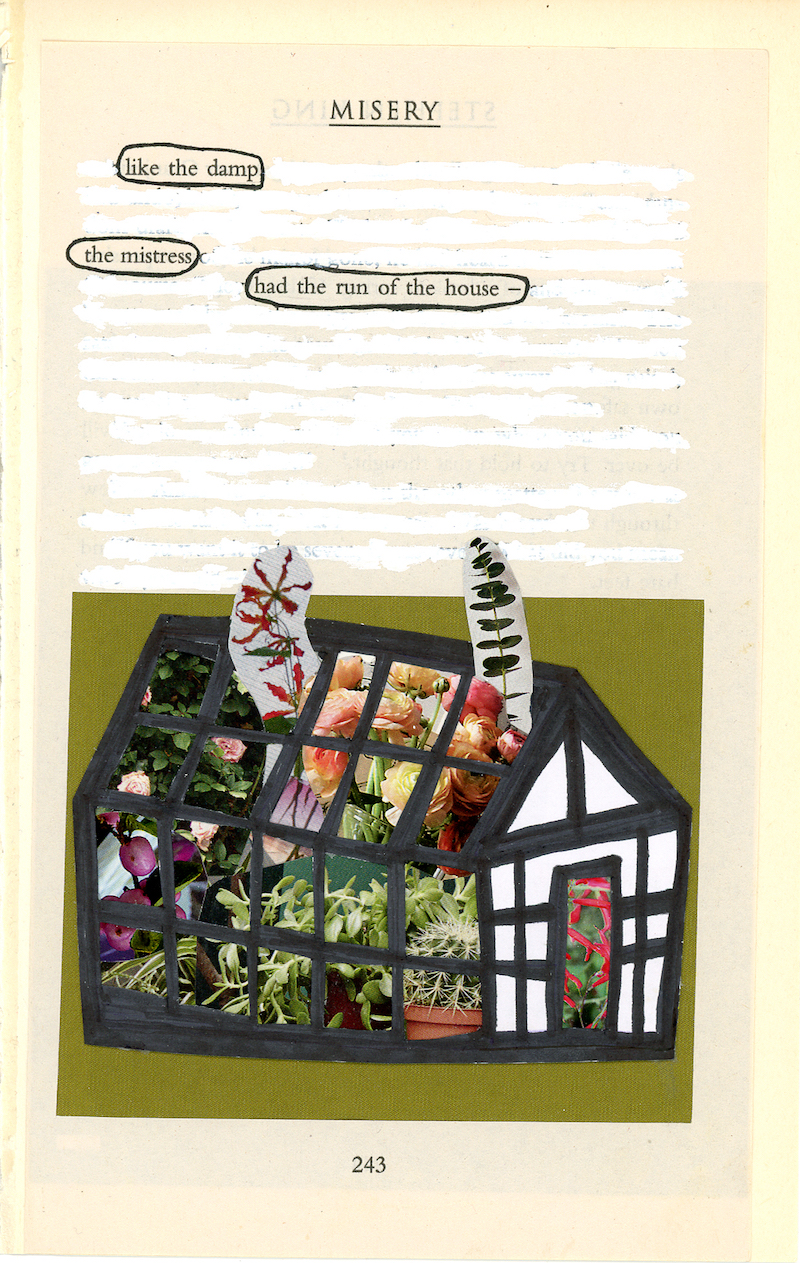

Sarah J. Sloat: I think of my work as creating something new, in part by eliminating something that exists. In erasure, the source text is a raw material. Through erasing, I am getting down to what I’d like to say. With the approach I use in ‘Hotel Almighty,’ removal is creation but it doesn’t stop there. Since I make my erasures directly on the page, I see the blank space as an opportunity. By adding visuals, I am augmenting or amplifying the text. I bring in elements that strike me, provided they are small enough to fit the page. Erasure is a kind of found poetry, and in the case of the poems in my book, “found” is apt since collage, too, is also made most often with found materials. There can be any number of sources in a piece, and those elements have also been removed from some other sources to gather in the new piece.

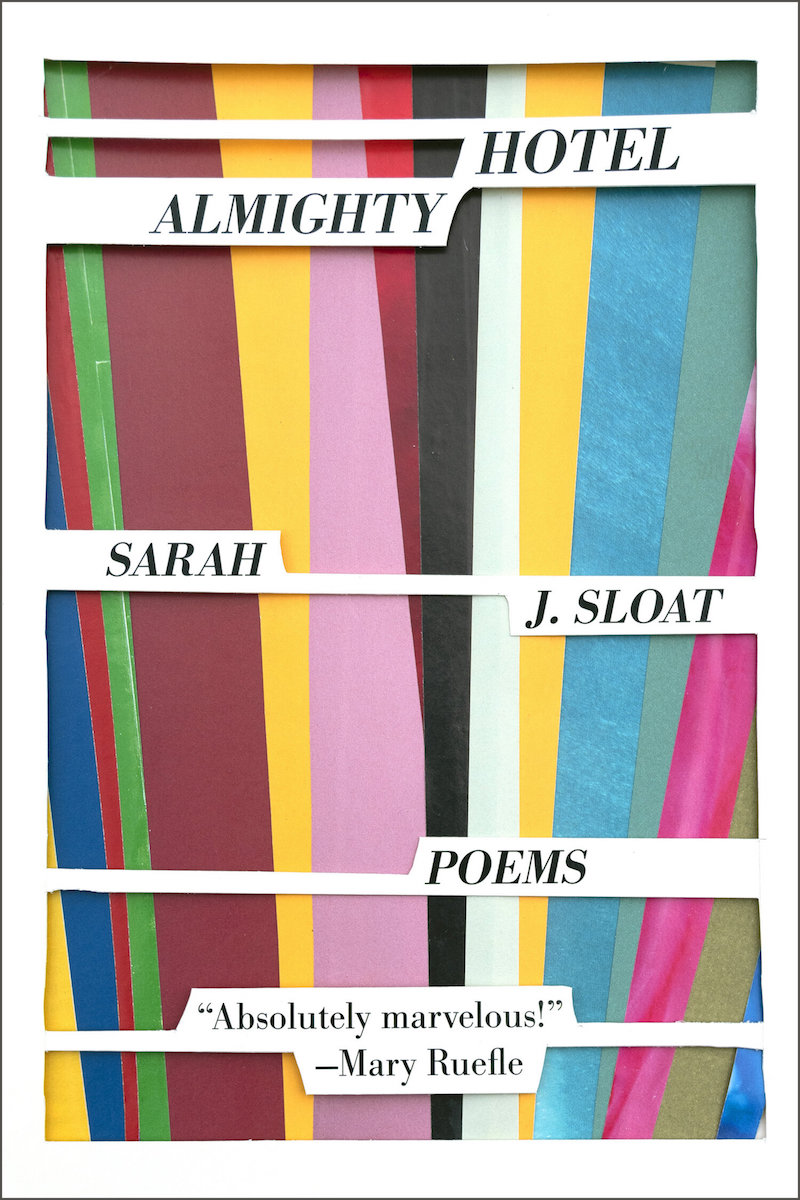

Sarah J. Sloat: ‘Hotel Almighty,’ book cover // Courtesy of the author

AD: Your practice involves reconfiguring the language and visuals of others to bring new meaning and connections to the fore. What role does authorship play in your practice?

SJS: In erasure, the goal is to find one’s own voice in the source text. In any erasure I do, the text is paramount—the poem has to have its own integrity, it has to stand on its own in a way that I recognise as mine. I am usually familiar with the source text because I think it’s only fair to read what I’ll be using. But I try to transform it into something different and new. If it’s a story about marriage, my poems will not be about marriage. I am not building upon the text, I am rending it from its context.

There is erasure poetry that works in other ways, of course. Some erasure works to subvert the source text. For example, a patriarchal text is turned into a feminist text. While I admire a lot of erasure done in this vein, it isn’t what I’ve done. My book ‘Hotel Almighty’ uses the vocabulary of ‘Misery,’ but the plot, characters and action of that book inhabit another world.

Sarah J. Sloat: ‘Like the Damp,’ from ‘Hotel Almighty’ and previously published in Tinderbox Poetry Journal // Courtesy of the author

AD: The poetry in your work becomes visible as a result of your collage and physical erasure of existing text, unveiling new meanings and relationships between language and space. What is the significance of the relationship between the visual and linguistic elements of your practice? In what ways has your visual practice developed alongside your writing practice?

SJS: I make the collage after the poem is complete, for that particular poem. But while I hope the visuals somehow speak to the text, that they’ll have resonance, I don’t try to draw a direct line between them. If there are lions in the poem you won’t find a lion roaming the margin of the page. I’d like the visuals to hold some aura or surprise of their own. And I leave it to the reader to make connections between visual and text.

In terms of my own development, before the project of ‘Hotel Almighty’ I was not a visual poet. I wrote poetry, sometimes it rhymed, usually it didn’t. I loved ghazals and triolets and free verse. I still love them, but I’ve gravitated toward the visual because I enjoy it. It’s wonderful and fun and mysterious. Not that poetry isn’t; poetry is the highest star.

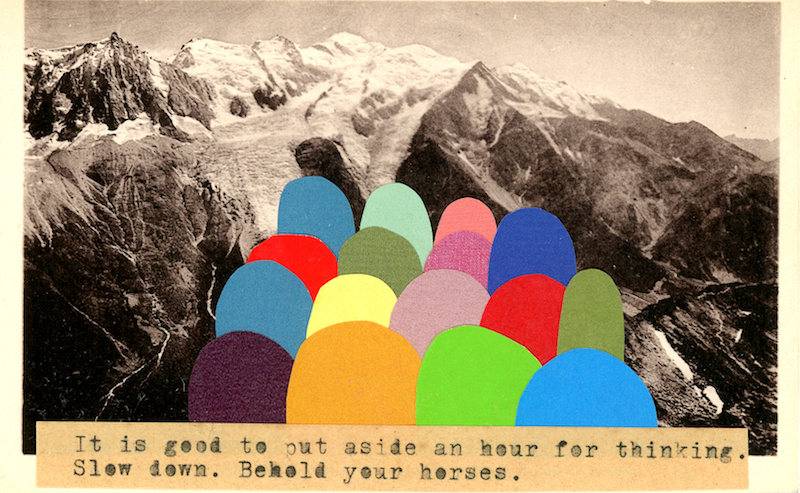

I’ve also made collage with found text that is not erasure, just accidental clippings from books or magazines. I keep a small notebook of aphorisms, some of which I’ve incorporated into collaged postcards. I have also made many collages absent of text. I love paper and color. But text is my native country.

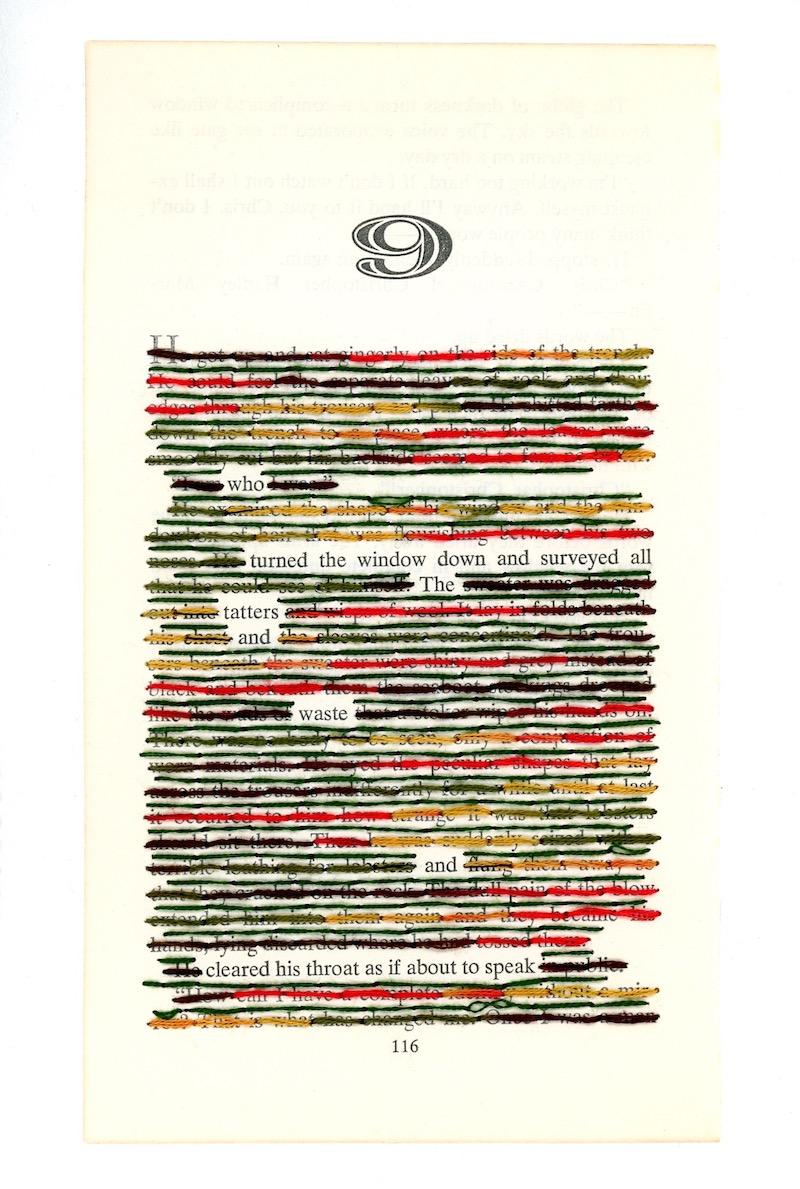

Sarah J. Sloat: ‘Tatters,’ Source text: Golding, William. Pincher Martin. Capricorn Books, 1956. Previously published in Quarterly West // Courtesy of the author

AD: Could you elaborate on the processes behind your practice? How do you choose your primary texts? Where do you collect your collage materials?

SJS: I have a lot of trouble finding texts that suit my aims. ‘Hotel Almighty’ was serendipity; ‘Misery,’ the source text, was assigned to me as part of a found poetry challenge. Otherwise, I have struggled to get comfortable with a number of books. If I love a book too much it makes me uncomfortable, as if I were desecrating a temple. If a book is abstract, the language can be stiff and soulless. I’ve had luck with pages from Ali Smith’s novel ‘The Accidental,’ though I do love it, and with a Dutch novella called ‘Sleepless Nights,’ and with ‘The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin.’ But it’s patchy—nothing has been as consistently rewarding as Stephen King.

In general, I look for a source text with good concrete nouns and verbs. You’d be surprised how hard that seems to come by! At the same time, since I am sticking to the page, I need a good, clear font, letters that are not too small or narrowly spaced and decent paper quality.

Regarding collage materials, I use mostly magazines, catalogs and books with pictures or illustrations. Occasionally, I find good garbage on the street. I like colored paper. Sometimes I use thread, and sometimes thread exclusively. I want the page to be inviting, to have its own atmosphere.

Sarah J. Sloat: ‘Behold Your Horses,’ postcard // Courtesy of the author

AD: Your work offers both a visual and textual experience for the viewer, with the finished work appearing as a publication. What influence does the medium of the book have on your practice?

SJS: I often think I’ve taken so well to this form because I love books. I like the crispness of black font on the white, off-white and yellowing page. Once you’ve erased swathes of text, you’ve made yourself a little canvas.

In an interview I did before this book materialised, I was asked where I would most like to show my work, referring of course to a gallery or physical space. I answered that I’d most like to see it in a book.

This article is part of our feature topic of ‘Poetics.’ To read more from this topic, click here.