by Ilyn Wong // Aug. 10, 2021

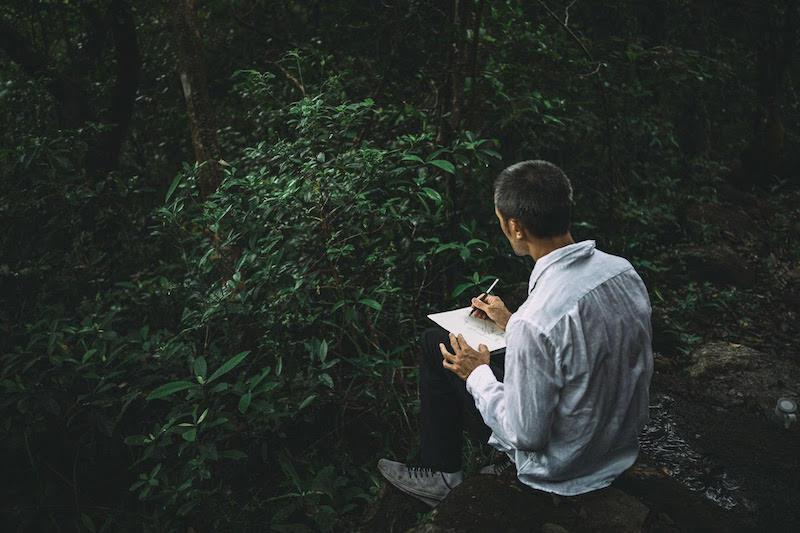

Zheng Bo was Gropius Bau’s 2020 In House: Artist in Residence, a residency which culminated in the current exhibition, ‘Wanwu Council 萬物社.’ The central question guiding the show is: how can humans sense the way plants practice politics? The artist has a daily practice of drawing plants, whether he is in Berlin or back in Hong Kong. He has also been talking to scientists and scholars, and leading what he calls “Ecosensibility Exercises.” Before one of these exercise routines that take place amid plane trees in the car park of the Gropius Bau—which he has renamed Gropius Wood—we sat down behind the museum, where weeds stubbornly poke out of the paved stonework ground, and chatted about why he advocates for plants to be seen as political beings. Speaking in a careful and considered way, which echoes his art-making, Zheng Bo talked about his relationship to plants, Daoist philosophy and poetics. Talking to him, I am reminded that while the consideration of non-human agencies is particularly topical in this moment, it is also, in fact, ancient wisdom.

Zheng Bo // Courtesy of the artist and Edouard Malingue Gallery, photo by Kwan Sheung Chi, 2020

Ilyn Wong: Can you help me understand what you mean by “the political life of plants”? You use the words politics and ideologies as things that plants practice. I understand this perspective as both giving plants agency while de-centering the human. I also assume that you’re not talking about an anthropomorphizing of plants, nor are you necessarily talking about the ways humans co-opt plant life for our political agendas. So why “politics,” as opposed to, say, the “desire” of plants?

Zheng Bo: When I say the “political life of plants,” the main goal is to push our understanding of plants. The scientist Roosa Laitinen, who studies the genetic basis of plant adaptation, told me that plants can adapt to their situation by changing their bodies. If we can see and understand this adaptation as a political practice, perhaps we can also see the ways plants can do things way beyond what we can do. I also think that we tend to see political practice as a uniquely human endeavor. To be political is the ultimate status of being empowered citizens. If we really want to see other forms of life on the planet as equal, thinking of them as political beings can really challenge our hierarchical views.

There’s been a lot of focus on the social life of plants in mainstream discussions. Perhaps one of the reasons I’m using the word political as opposed to social is that we tend to also romanticize plants’ social lives. When I think about human politics, there is competition, fear and power play; but there is also family, collaboration and relations. Similarly, plants are not always amenable to each other. In other words, talking about the political life of plants is also seeing them for their complexities. The title of the film ‘The Political Life of Plants’ is a huge title. I don’t think I’ll be able to work on it alone. The project is meant to provoke something, so that more people might start thinking about this.

IW: The other scientist you talk to in the film is Matthias Rillig, whom you ask about the fascinating relationship between trees and certain fungi, and how they live in symbiosis. In the film, Rillig says that it seems like a rather risky endeavor—to rely on another species for nourishment and survival. And perhaps I am doing exactly what you said we humans do, that we romanticize the social life of plants, but I can’t seem to find a way to describe this relationship—one that doesn’t seem exactly necessary or logical—as anything other than beautiful or somehow poetic.

ZB: The relationship between the trees and the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi is a relationship of radical trust. It happens all the time. We, for example, have a microbiome. We don’t think about it, but our bodies trust the microbes that live inside us. The difference is that the microbes and our bodies are still separate entities, whereas the trees and the fungi not only live in each other’s bodies, they actually penetrate each others’ cells. In fact, I asked Matthias why we don’t just treat them as one being. And the reason, he told me, is that when they need to generate the next generation, they have to do it separately. The fungi still produce their own spores, the trees still produce their own seeds, and then the next generation still have to find each other and find that trust, they still have to penetrate each other so that the relationship is renewed. And yes, it’s true, it’s so romantic and so poetic, and it’s way beyond what we can do.

IW: When I think about poetics, I think about a figuration outside of language. There is something poetic about the way you spend time quietly with plants, making simple drawings of them throughout the seasons. Do you think about your practice in that way?

ZB: For me, poetics is about using a whole array of sensibilities to sense life on the planet. I don’t write poetry and I haven’t thought about my practice in relation to poetics, but I do think about sensing time. If I sit here and just look at a plant, it’s very difficult to be engaged and to be absorbed. But when I draw them, that activity involves a coordination between my hands and eyes, and then I am able to spend a few hours being totally absorbed by the forms of the plants, by their life, by their relations, etc. So that’s why I use “sensing” in English, rather than “knowing” or “seeing” because “sensing” is about using all our sensory experiences, to get beyond the mundane, the rational.

In Chinese aesthetics, there is something called “虚” or the “void.” It’s not a perfect translation, but the idea is that it’s important to leave some so-called empty space. That’s where the beyond happens. By sitting with plants and talking to scientists, I recognize that there are many things beyond our capabilities and comprehension. It leaves something beyond our intellectual understanding. I think that’s important to our sense of poetics.

IW: Your drawings are organized according to Chinese solar terms, which have 24 periods as opposed to 12 months. I grew up in Taiwan, but I wasn’t aware of this system. What I found when I looked it up is that it’s not just a more detailed division of the seasons, but that each division is accompanied by representative flora, fauna, winds and even proverbs, some of which I am familiar with as everyday idioms. To think of the calendar in this way considers it as so much more than a time-keeping device, but to embed the rhythms of nature into our experiences and language.

ZB: I think what you’re suggesting is that the premodern Chinese were highly attuned to the seasons and to other forms of life. I grew up on the edge of Beijing, and have mostly lived in big cities. In industrialized societies, most people don’t really have contact with other forms of life or seasons, so we completely lose touch and our language becomes very lifeless. Our language used to be alive and full of references to what happens throughout the year, and that’s what I’m trying to bring attention to by drawing outside, by drawing living beings, and by using these solar terms to prompt viewers to think beyond the four seasons. Through working with plants and doing projects outside, I’ve become highly attuned to seasons and plants.

IW: Can you talk about your work in relation to Daoist sensibilities?

ZB: Going back to my conversation with Roosa Laitinen about adaptation, I think Daoism brings awareness to our need to adapt, particularly our need to adapt to non-human situations. It focuses more on cultivating our abilities to adapt and to let go, to enjoy the rain when it rains and the sun when it’s hot. And going back to radical trust, we have to trust that the larger system or situation is working and we don’t need to do too much. Maybe we do a little bit when it’s needed, but plants are wise, they know what’s best for them; rivers are wise, they know how to flow. We need to trust that they are as wise as us. A Daoist would say the larger system is much wiser than us.

IW: Do you think that’s true in our state of ecological crises?

ZB: I think a lot about this Daoist concept “無爲,” or “non-coercive action.” It’s not about doing nothing, but about sensing the complex set of forces and finding the right way to do something. It requires patience and humility. When I make these drawings on small pieces of paper with simple material, it allows me to actually sense the plants, to really spend time with the plants. Even though I studied computer science, I was never interested in media art. I’ve gone increasingly towards simpler forms—to drawing, conversations, gathering people to write a manifesto—simple forms that require very little resources and technology. These are Daoist sensibilities, which try to find the simplest way of doing things and sensing the planet.

Artist Info

Exhibition Info

Gropius Bau

Zheng Bo: ‘Wanwu Council 萬物社’

Exhibition: June 21–Aug. 23, 2021

berlinerfestspiele.de

Niederkirchnerstraße 7, 10963 Berlin, click here for map