by William Kherbek // Nov. 19, 2021

“A joke can be seen as expendable social capital,” writes Kasia Fudakowski in her new autobiography ‘The Roll of The Artist’ (2021, Strzelecki Books). The artist continues: “Historically a woman first had to establish herself as serious before she could invest in a joke.” Fudakowski’s formulation is a profound consideration of the female condition in art, and of humour as an aspect of social capital. Sooner or later, everyone working in comedy will hear the adage “comedy is serious business.” Cliches’ familiarity often elide their own profundity, but the relationship of comedy to capital, as Fudakowski demonstrates in her autobiography, is no laughing matter. Lawrence Ferlinghetti defined the poet as someone “constantly risking absurdity.” The artistic practice that Fudakowski reflects upon in ‘The Roll of the Artist’ belies the revered Beat poet’s dictum. Instead of “risking” absurdity, Fudakowski’s art often has sought to draw it out, to see the absurd, and even the horrifying, in the quotidian. The publication of her autobiography offers occasion to think about the ways artistic influence can move across media and genre.

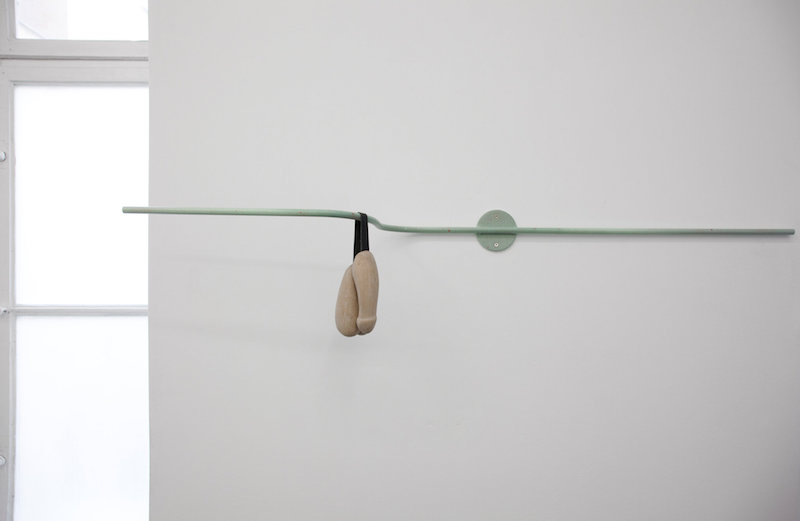

Kasia Fudakowski: ‘Double Standards (A Sexhibition),’ installation view at ChertLüdde, Berlin, 2017 // Photo by ChertLüdde, courtesy of ChertLüdde, Berlin and Kasia Fudakowski, Berlin

Fudakowski has long been interested in comedy as an art form. In the book, she discusses the influence in particular of the enigmatic, controversial American comedian Andy Kaufman on her work. Kaufman has fascinated creative people across media and form for decades. The Jim Carrey film ‘Man on the Moon’ and the band R.E.M’s song of the same title both consider the unresolvable, indigestible qualities of Kaufman’s performances. For Fudakowski, it is the very irresolution of Kaufman’s work that has made it so influential for her. She notes, in an appositely extended section in her book, that Kaufman “didn’t tell jokes.” Kaufman’s social capital derived from a kind of comic speculation: a performance might or might not be funny. This unresolved state was where the value lay. Fudakowski referenced Kaufman directly in her 2017 exhibition, ‘Double Standards (A Sexhibition).’ Presented in Berlin at Fudakowski’s gallery ChertLüdde—and no doubt competing with various other sexhibitions taking place on the same night—the piece was regarded by Fudakowski as a way of “releasing” herself from Kaufman’s influence. The exhibition, which included sculptures of stylised body parts, also included a text by Fudakowski in which she imagines an encounter, mercifully entirely fictional, between Kaufman and another great influence on her practice, the artist Lee Lozano. Fudakowski’s tale of toxic love was perhaps intended as an exorcism, but it also channels one of the most familiar forms of popular creative practice in digital culture: ‘shipping. The creation of narratives about characters in an artwork becoming romantically involved has been known to influence the production of the source artwork. In producing an art-ship between Kaufman and Lozano, Fudakowski gestures toward the futility of “escaping” influence.

Kasia Fudakowski: ‘Double Standards (A Sexhibition),’ installation view at ChertLüdde, Berlin, 2017 // Photo by ChertLüdde, courtesy of ChertLüdde, Berlin and Kasia Fudakowski, Berlin

Humour is also at the heart of Fudakowski’s interest in Lozano, whose works she describes as “violent, cruel, erotic and goodman funny. They’re aggressive, they elbow, take up space, buzz and ooze. They nailed me.” As an example, she includes the text of ‘Party Piece (Or Paranoia Piece)’: DESCRIBE YOUR CURRENT WORK TO A FAMOUS BUT FAILING ARTIST FROM THE EARLY 60S. WAIT TO SEE WHETHER HE BOOTS (HOIST, COP, STEAL) ANY OF YOUR IDEAS.

Fudakowski loves the aggression in Lozano’s imprecation. It is perhaps a bit too blunt to be satire, but it is something more like a prompt to farce. Such narrative creation is also a central aspect of Fudakowski’s work. Not least in the case of the latest iteration of the work that ‘The Roll of the Artist’ was produced to accompany. An exhibition of the extended sculpture ‘Continuouslessness’ at the Leopold-Hoesch-Museum in Düren provided Fudakowski with the occasion to reflect on the arc of her creative life. The work itself is a kind of autobiography, slowly accruing new panels each time it is exhibited, but also tracing back to its earliest creation and encompassing all manner of phases of Fudakowski’s practice, a compendium of materials and motifs, metal, broom brushes, hair, even a short film she made for a show at the Düsseldorf Kunstverein linked together to comprise a work that will remain permanently ‘open’ to new additions. The work is, in its ever-expanding character, intrinsically humorous; Fudakowski, like Jacob Marley in ‘A Christmas Carol,’ literally carries a metal chain she has forged in life with her from one exhibition to the next, but it is also poignant. It reflects both the anxiety of one’s creative past, essentially an acceptance that one cannot truly escape it, but also a sense of unease about the future: will the past someday become too much for the present to be experienced fully?

Kasia Fudakowski: ‘Türen,’ 2021, installation view at Leopold-Hoesch-Museum, Düren // Photo by Peter Hinschläger, courtesy of ChertLüdde, Berlin and Kasia Fudakowski, Berlin

The articulated panels of ‘Continuouslessness’ materialise (and satirise) the famous dictum of E.M. Forster in ‘Howards End’, “only connect,” an injunction to artists to fuse emotion and form as a means of creating enduring aeshtetic dialogues with the world , but Fudakowski’s works are often about a kind of disconnect, the articulation of disarticulation. Also featured in ‘The Roll of the Artist’ are images from Fudakowski’s performance ‘Did I Ever Have A Chance’ (2015) during an exhibition at the Museo Marino Marini in Florence. The performance is a mini-drama (in more ways than one) in which The Artist and The Curator attempt an interview beset by misunderstandings, disasters and crimes. The lineage of British stage comedy, not least the eternally-running West End farce, ‘The Play that Goes Wrong’ is built on a similar premise: only in failing can the “performance” be a success. ‘Did I Ever Have a Chance’ is both a live and rhetorical question in Fudakowski’s handling. Her answer is less “no” than the improviser’s variation: “no, and….”

Kasia Fudakowski: ‘Sexistinnen,’ 2015, Installation view Art Basel Statements // Courtesy of the Artist and ChertLüdde, Berlin

Kasia Fudakowski: ‘lower your ambitions (blue),’ 2015, handmade mop with dyed cotton, with bucket, colours vary // Courtesy of the artist and ChertLüdde, Berlin

Drama is clearly a form that fascinates Fudakowski. Also in 2015, she created the works of ‘Sexistinnen’, several sculptures and a video performance in which Fudakowski dramatises the self-sabotage she describes witnessing in art and in life, as a part of the internalised misogyny that characterises life in the 21st century patriarchy. She includes the excruciating script of the performance in ‘The Roll of The Artist,’ and notes that members of the prize jury at Art Basel were unimpressed by Fudakowski’s exercise in immersive theatre. The work wins neither prizes nor sells, except for a sculpture involving a menacing blue-dyed mop she has titled ‘Lower Your Ambitions.’ Reading her description of the events, a genuine note of disappointment seems to creep into Fudakowski’s writing, but perhaps it too is ironically intended. If failure is the metric by which the work should be judged it proved a major success, with the art world providing her with an enduring “no, and…”

Indeed, perhaps this is one of the great takeaways from Fudakowski’s works, less an artistic paraphrase of RX Hector’s “all my losses was lessons” than a sense that learning invalidates the categories of winning and losing. No win is permanent; loss is only a matter of context. Humour can be a coping mechanism in the face of overwhelming pressures, but it can also provide a unique space where the prerogatives of the power systems hold no jurisdiction. Fudakowski’s work, at its best, can act as a guide to creating and navigating this space.

This article is part of our feature topic of ‘Humor.’ To read more from this topic, click here.