by Nina Prader // Jan. 25, 2022

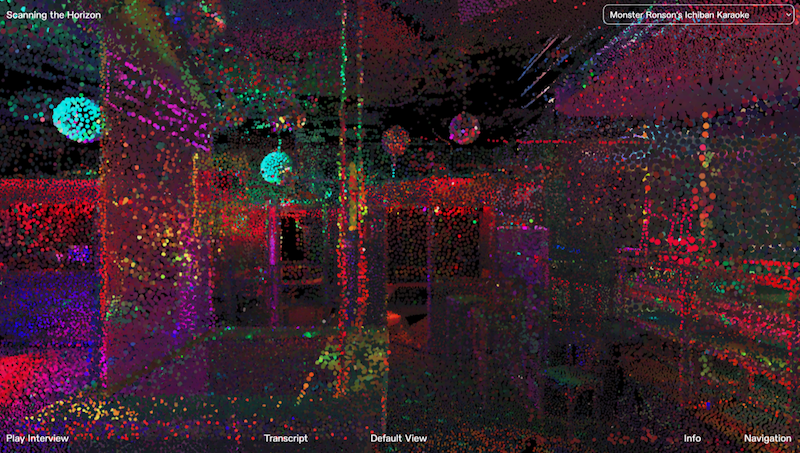

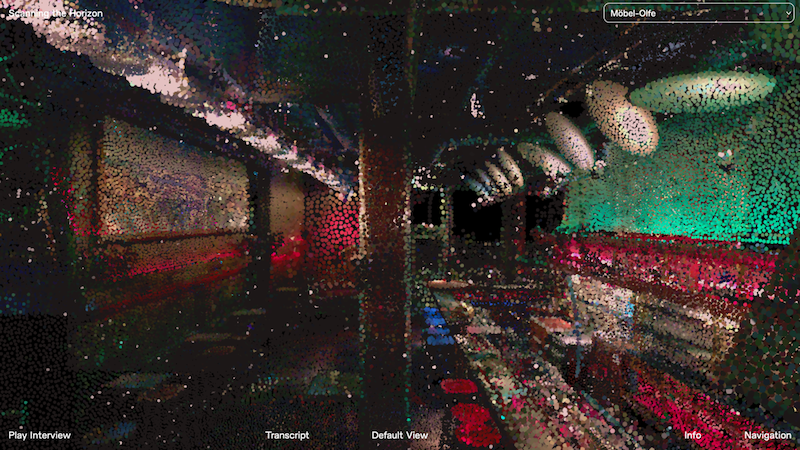

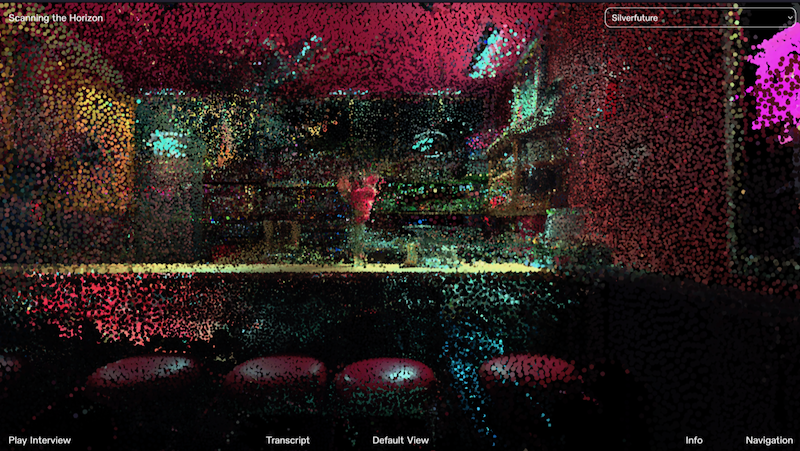

While we endure the pandemic, digital spaces have become an everyday phenomenon. Visual artist and co-director of TIER—The Institute for Endotic Research Benjamin Busch welcomes viewers to navigate five digital landmarks in his project ‘Scanning the Horizon,’ first launched in December 2021 at the Schwules Museum. Through 3D Lidar technology, he performs a cultural and historical service by scanning active queer cultural spaces in Berlin. Digitizing these spaces transforms them into an openly accessible archive. Multiple 360-degree scans are translated into colorful points in software, which creates a pixelated effect. The virtual spaces appear as if made of pinpricks of light in an impressionist painting.

The project architecturally archives spaces of joy, self-discovery and community, making it possible to digitally experience BEGiNE-Treffpunkt und Kultur für Frauen e.v., Möbel-Olfe, Monster Ronson’s Ichiban Karaoke, Silverfuture and Prinz Eisenherz Bookstore. In the future, it might be possible to order a drink at the digital bar, but, in the meantime, Busch sets up powerful questions about archiving local, queer histories and public spaces in Berlin. We spoke to him about the project and its goals going forward.

Benjamin Busch: ‘Scanning the Horizon,’ 2021 // Screenshot by Nina Prader

Nina Prader: Scanning is a very useful and also controversial method and technology. You, as the scanner, are not completely neutral. Your personal story also affects the lens of the scanning device. What has scanning meant to you during the process of creating the project?

Benjamin Busch: My background is originally in architecture, before transitioning to a visual arts practice in 2017. As an architect, I was working with 3D scanning in a very functional way to document existing buildings. I was amazed by the beauty of the point cloud scans. I wanted to start working with the virtual material as an artistic medium, as a form of lens-based documentation. I began experimenting. My first own artistic approach to 3D scanning was a video I co-produced with Sadia Sharmin, titled ‘Amader Pathagar (A Library of our Own)’ (2021). It allowed a particular view into the activist community library in Karail Basti, Dhaka—to be able to see the space inside out, to see the inside from the outside using this particular technology. I found the distancing effect to the space very powerful from an aesthetic and emotional perspective.

Usually, Lidar spatial scanning would rather be used to document historic buildings like cathedrals, castles, or these kinds of irreplaceable cultural heritage monuments. Most people will recognize the technique from Google Earth because it has been used in their software for over a decade to create 3D maps of urban spaces on the whole planet. It can have an aesthetic of domination over space. To go to these spaces in Berlin, to scan them, and make a claim that these spaces are worthy of this form of archival documentation, this claim that a queer space like a queer bookstore, bar, or performance venue has the same cultural value, was what I was interested in. As a visual artist, I was interested in reclaiming this tool for visual representation: to tell my own story or to tell our own stories as people who identify as queer. So the first part of ‘Scanning the Horizon’ is the archival gesture of creating the raw scans themselves. I see the archival gesture as the work.

Benjamin Busch: ‘Scanning the Horizon,’ 2021 // Screenshot by Nina Prader

NP: What was your methodology to collect this warm data—the audio recordings and oral histories?

BB: The additional layer of warm data allows the spaces to speak for themselves. It is a further elaboration to the visual material, which could be seen as cold data. When we visited the five spaces, we had a series of questions with us that we could use as cartography for our conversation. I am grateful to Kevin Junk for support with the interview and editorial process. Ultimately, the conversations flowed and developed organically. The technical details and historical dates were not the focus, but rather how the space operates. What are the ideological and political stances? Do you have a door policy? Is it important to include everyone or, rather, to filter the space? Each space also has a different business model, spanning from squat to traditional business. To connect to the scans, we also talked about the physical spaces themselves.

Mostly the interviews created a sense of what it is like to be in the space when it is not an empty container. These scans are like empty stages. Following queer theorist José Esteban Muñoz’s musings on Kevin McCarty’s photographic series ‘The Chameleon Club,’ I like to imagine the scans in combination with the interviews create a kind of imaginary space, inviting the viewer to populate it through their imagination and projections.

Laser scanner at Rauschgold (production photo) // Photo by Benjamin Busch

NP: How did the various community representatives respond to the spaces being scanned?

BB: There is this kind of utopian fascination with this form of representation just as it is. I was surprised by how excited people were to participate. They were generally not skeptical of the technique itself. Some of the spaces were wary because they wanted to know whose space the project would be presented in. I did have some worries about being able to realize the website. The scan as an archival gesture enables the data to enter into a private collection, which can be protected. To make it public is to move this private material online. This movement of publishing the material into a public forum is the challenge of the work.

Benjamin Busch: ‘Scanning the Horizon,’ 2021 // Screenshot by Nina Prader

NP: It is such a powerful gesture to make these places accessible to all via the digital medium. However, these places are still often subject to hate crimes and discrimination. I was wondering if there were any sort of safety measures you had to worry about in terms of bringing these spaces online?

BB: All of the spaces on the website are public. In real life, it is possible to walk in from the street and check them out. However, they have different door policies. What I think is important to mention is that this type of public accessibility represents a privilege that not every space has in Berlin and around the world. The need to create a space that is private, protected, safe, or opaque rather than transparent, is a need that is probably more common among queer spaces than not. For that reason, it was impossible to include many spaces in the same visual format.

Benjamin Busch: ‘Scanning the Horizon,’ 2021 // Screenshot by Nina Prader

NP: Your project celebrates queer life. On one hand, this digitization functions as an archiving process, on the other, it also functions as a monumentalizing process. Currently, it speaks to a very local Berlin history. Would you think about also performing this service internationally? Could it also be a tool to document, commemorate and celebrate places that no longer exist, like the club Pulse in Orlando?

BB: This is pointing to the future of the work. There is a need to document these spaces for perpetuity and continuity. Through digital media these documented spaces can be revisited indefinitely in the future. There is a kind of memento mori embedded in the work in its archival temporality. So, the monumentalizing function rests in the archival gesture.

In the future, it will be very interesting to revisit these scans. In the coming years, as we see spaces become more virtual, as we see spaces enter into 3D environments, like with photogrammetry or augmented reality, we might start to think about what it means to not only construct narratives about abstract utopian futures, completely separated from our physical realities and lived experiences, but reach into the archive to look for remnants of past spaces, memories and histories to revisit in new relation to our hi-res media present. This might breathe life into them again in this growing virtual space. I am engaging with this in the next phase of the work. I hope to recover some of those lost utopias.

This article is part of our feature topic of ‘Digital.’ To read more from this topic, click here.