by Alison Hugill // Mar. 29, 2022

This article is part of our feature topic ‘Occupation.’

As part of the upcoming Venice Biennale, the Mondriaan Fund has invited Estonia to exhibit as guests in their historical Rietveld pavilion. While Estonia has participated in 13 biennales in Venice, this is the first time the country will present inside the Giardini. For the occasion, Tallinn Art Hall curator Corina L. Apostol has teamed up with Estonia-based artists Kristina Norman and Bita Razavi to offer the exhibition ‘Orchidelirium: An Appetite for Abundance,’ drawing on the life and works of Emilie Rosalie Saal.

Saal and her husband, writer Andres Saal, lived for 20 years on the island of Java, then part of the Dutch East Indies, where Emilie engaged in the occupation of hunting for and depicting sought-after species of tropical orchids, in her rich series of botanical artworks. While the Saals were marginal figures in Estonian history, Apostol, Norman and Razavi unearth their story as an access point into a wider history of colonialism and ecological exploitation, and its effects in Estonia and Indonesia today. We spoke to Apostol about the themes explored in the upcoming exhibition and the critical approach to colonial histories taken by the artistic team, in collaboration with Indonesian artists and researchers.

Artistic team and commissioner, from left: Corina Apostol, Bita Razavi, commissioner Maria Arusoo, Kristina Norman // Photo by Dénes Farkas, CCA Estonia

Alison Hugill: Why did you choose to enter into complex topics around colonialism and ecology through the figure of the orchid and the so-called “orchidelirium” it caused in 19th century Europe?

Corina Apostol: This project started with a conversation I had with artist Kristina Norman. We had a common interest in dealing with colonial narratives in Eastern Europe. Here, in Estonia, the conversation has largely been from the perspective of Eastern Europeans as having been occupied by the Soviet Union. And, before the Soviet Union, by different powers coming into the region. We wanted to do this exhibition that flips the narrative and talks about how, in Estonia’s history, there have also been people who manifested these kinds of colonial ambitions themselves. This duality was interesting because people from Estonia often feel like they are colonized. But what happens when you are in the position of privilege, and you have this colonial power in a different context, like Indonesia?

Emilie and Andres Saal on their mansion veranda in Weltevreden, Jakarta in the early 20th century // Courtesy of the Estonian Literature Museum

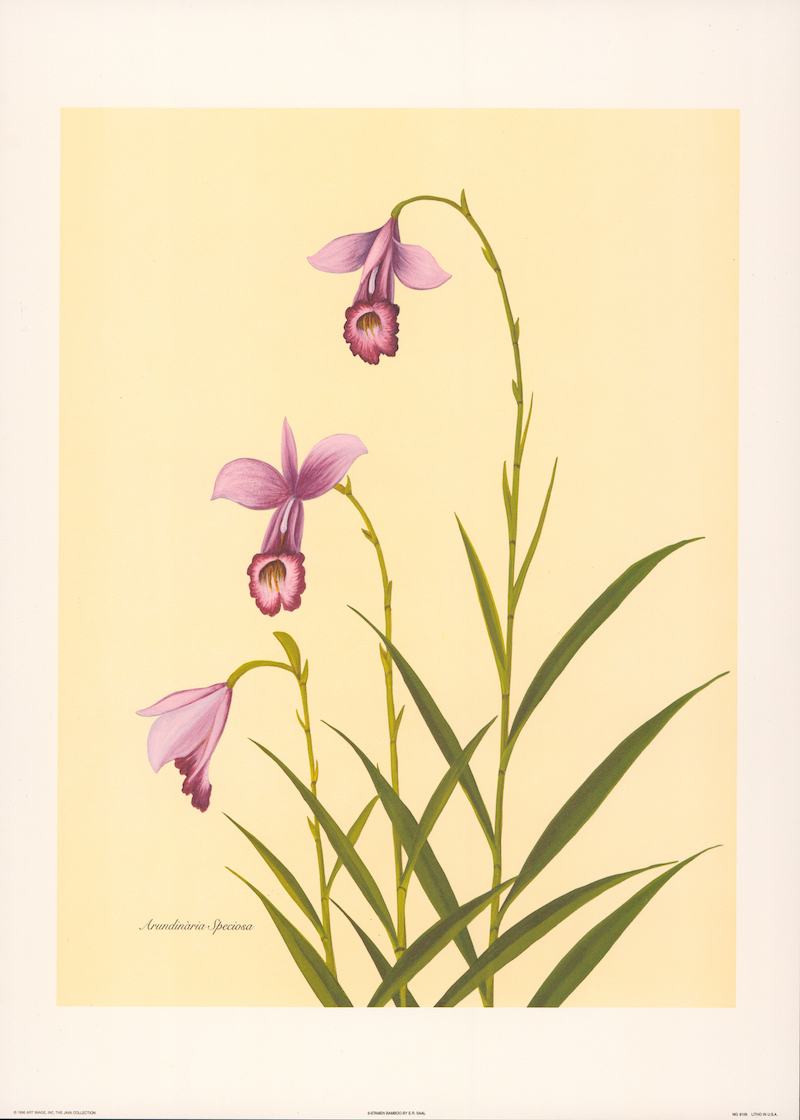

Emilie Rosalie Saal: ‘Bamboo Orchid,’ ca. 1910-1920, lithograph, 635cm x 483cm // Courtesy of Corina L. Apostol

AH: Can you tell us about the Estonian historical figures you selected as entry points into this discussion?

CA: With Kristina, we discussed different case studies, one of which was Andres Saal, a writer, cartographer, linguist and photographer. In his biography—literally in the footnotes—there were mentions of his wife. They were living in the 19th century, which was still a deeply patriarchal time, so his wife was mentioned mostly as his companion. But what drew my attention was that she was also referred to as an artist, and she drew botanical artworks during their stay in Indonesia. I was curious what the paintings looked like and whether they were still around.

After living in Indonesia for about 20 years, they had retired to Los Angeles. So I contacted different museums in the US. I was digging up museum archives and trying to find out more about her and her work. I found a newspaper article from the Los Angeles Times that mentioned her, with a grainy photo of her and her paintings, and said she had displayed her entire collection of 333 botanical artworks in the Los Angeles Museum of History, Science and Art and they drew attention to a series of 100 orchids that was part of the collection. The article highlighted that it was very unusual for a woman at that time to go on this kind of expedition, hunting for rare orchids.

I started to look more into the histories of orchid hunters and people going into remote areas in search of these specimens. I also discovered that, at the time, the plants themselves were more expensive than jewelry. The research crystallized the concept of the project for me in terms of what hides behind this duality: the obsession and fascination with the exotic and also the more complex and painful and destructive aspect of this obsession. We’ve now had two years of discussions with communities and artists and scholars in Indonesia, about what this means for them as well.

Emilie Rosalie Saal on horseback on Java Island, stereo photograph by Andres Saal, ca. 1910-1920 // Courtesy of the Estonian Literature Museum

AH: Why was it important for you to take Emilie Rosalie Saal out of the footnotes of her husband’s story?

CA: It’s been an important part of my practice to highlight the contributions of women artists and people who have been erased from history. That’s partly because of who I am and my background and the general historical oversight of women as creators, especially in Eastern Europe. It was also a challenge to put Emilie’s life story back together. In Estonia, her name is not well-known. But when she went to America, she eclipsed her husband and became the protagonist herself. This is not to say that she is some kind of heroine: the exhibition is a lot about the choices she made and how she also contributed to the colonial project.

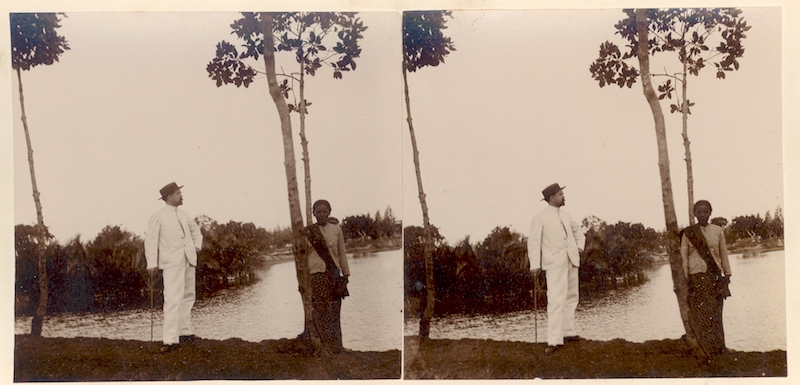

Andres Saal and servant on rubber plantation // Courtesy of the Estonian Literature Museum

AH: You mention the layers of colonial privilege in the Saal’s story: they were colonized by Russians, but also acted as representatives of white European colonialism in Indonesia (then the Dutch East Indies), where they lived. Their impact on the landscape and indigenous people of the region is taken into account, as well. Why is this story relevant today?

CA: I moved to Estonia three years ago, so I am somebody looking from the outside at the history while being on the inside. I love going into these details. The story is not well-known in Estonia: Emilie is a super marginal figure. Part of it was to focus on bringing her out of the margins.

Living in Estonia, there’s been a growing kind of nationalism that I’ve observed and a consolidation of traditional values under Far Right political parties. They’ve also used the pandemic to bolster support for anti-immigration policies. The project is a response to that and to counter these kinds of narratives.

The notion of Estonia as a perpetual victim of colonial powers is part of the rhetoric that I’ve observed and I wanted to show that they have also been in other positions. Discourses on race haven’t been analyzed enough in cultural institutions here. Dealing with the other and engaging with a history of racism in Eastern Europe hasn’t been widely addressed. Part of this project is tracing the repercussions from the 19th century and putting them in dialogue with what is happening today, in terms of environmental degradation, as well. Nature is not something that is neutral or outside categories of gender and race.

AH: Why did you choose to work with artists Kristina Norman and Bita Razavi for the pavilion?

CA: As I mentioned, the project started with this conversation I had with Kristina Norman, which was meant to be an exhibition at the Tallinn Art Hall. But while we were researching, we heard about this open call for the Dutch Pavilion, which seemed to be an amazing coincidence. We decided to apply and also invited Bita Razavi to be in conversation. We wanted an artist with a conceptual approach, who could think critically about history. Something else that we all share is that we are outsiders and insiders in Estonia, at the same time.

I am from Romania and I live in the Baltics. Kristina is part of the Russian Estonian community and her films usually deal with issues of duality and segregation between the Russian and Estonian communities locally. Bita grew up in Iran, moved to Finland for her studies and now she works between Finland and Estonia. For me, it was important to have the synergy of working with artists who share this liminal space and who can bring criticality to the subject matter.

From the beginning we also wanted to invite Indonesian creatives to be in dialogue with us. We will have a dancer called Eko Supriyanto, who is going to do a video intervention, which is being filmed now in Indonesia. And we’ve had an amazing advisor, Sadiah Boonstra, who is Dutch and Indonesian and contributed a lot to the research of the project.

Kristina Norman: ‘Orchidelirium,’ 2022, still from film trilogy, digital video with sound, total running time 35 min. // Photography by Erik Norkroos, courtesy of the artist

AH: Can you tell us about some of the works?

CA: Kristina is often working with uncomfortable stories and marginalized memories through the medium of film. She had the idea to do a trilogy dealing with the Saal’s life story and begin by discussing the context in Estonia in the 19th century. She’ll then bring the narrative into the present. She began by researching Manor Houses, these elite houses that belonged to Baltic Germans, where Estonians were working as serfs. She draws on Emilie’s biography, that she’s coming from this context. Art was one of the few occupations that women were allowed to pursue at that time. Another film deals with the metaphor of entrapment, and the exchange between people inside and outside the cage. It explores histories of slavery and serfdom. The final film, which she’s working on now, is being filmed in the Netherlands. She’s working with an orchid nursery and examining this fascination with mass-producing and cloning orchids and how the process has been mechanized.

We invited Eko to respond to this and the archive of colonial images I’ve compiled with a video work from Indonesia that is looking at the histories of sites, like the botanical garden of Bogor, where Emilie Saal went to paint her orchids, which was built on a sacred forest of trees on indigenous land. It was razed and replaced with a kind of European botanical institute on top of it. They’ll be offering these gestures of resistance and remembrance of the sites that have been forever altered.

Bita is creating spatial installations and dealing with the notion of privilege that is key to the project. In one intervention, the audience will be divided and have a bodily experience of privilege and separation. I don’t want to reveal too much. She’s also building a kinetic sculpture, leaning into Estonian mythology.

b210 architects: sketch for Estonian Pavilion, 2022

AH: Estonia has participated in 13 Biennales, in different venues across Venice. Can you tell us a bit about the venue for the Estonian Pavilion this year and its relevance to the theme?

CA: The Mondriaan Fund, who takes care of the Dutch pavilion, wanted to take a break and offer it to a country who historically hasn’t had representation in the Giardini. Younger nations, such as Estonia, aren’t able to have their own building there. So they decided to go into the city and chose Estonia for the takeover, because of the strength of previous years projects in Venice.

The building itself was designed by Gerrit Rietveld and is very simple and meant for modern art, which makes it a challenge to work with film, sound and installation in it. Besides the history of Dutch colonialism that is an obvious link to our project, there are also materials like marble in the steps to the building. I found some fascinating connections with activist groups in Indonesia fighting against companies who are mining for marble. There is a group of women-led activists among the Mollo people, in this mountain complex where Emilie used to go on her expeditions, who today protest by weaving textiles to put on the mountain symbolically to protect it from those who want to excavate there without their permission. There are so many overlapping connections to be explored.

Exhibition Info

La Biennale di Venezia

Estonian Pavilion: ‘Orchidelirium: An Appetite for Abundance’

Exhibition: Apr. 23–Nov. 27, 2022

Opening Reception: Apr. 20, 2022; 1:15pm

orchidelirium.ee

Netherlands Pavilion, Giardini, click here for map