By Kimberly Budd // Apr. 29, 2022

This article is part of our feature topic ‘Occupation.’

Oral histories, storytelling, and their interconnectedness to land and water are vital to First Nations culture and art in so-called Australia, where Indigenous systems of knowledge continue to be disrupted, destroyed and denied in order to prop up the occupying settler-colonial state. The 23rd Biennale of Sydney, ‘rīvus,’ examines the centrality of water to understanding and challenging the extractive paradigm through which settlers have framed the natural world and advanced the colonial project.

As part of the Biennale, Wurundjeri Woi-Wurrung Elder Uncle David Wandin contributed to the educational video series ‘River Voices.’ He describes the deep spiritual significance of the Birrarung Marr (the Yarra River) to Wurundjeri people, sharing ancestral stories that recount its creation.

“We have oral traditions of watching it form […] and that goes back thousands and thousands of years, longer than the 60,000 years we are known, scientifically, to be in this country. I have worked with geologists who tell me geologically how the Yarra River formed, and yet it dovetails into our knowledge of how the river formed, so at some stage we were either fantastic geologists or we were actually here to witness the birth of the Yarra River. That’s what holds its spiritual connection […] When you stand on the Yarra and think of the story that was passed down by the ancestors for many thousands of years, you feel a deep connection to the waterway itself.”

Examining what listening to the river might look like in practice, the Birrarung Marr (the Yarra River) is curated as a participant in this year’s program, along with other major rivers, wetlands, salt and freshwater ecosystems within Australia. Their voices are positioned to prompt an evaluation of their political agency, so as to counterpose them against settler capitalist occupation. One way to do this is to grant legal personhood to rivers in an attempt to protect ecosystems from further degradation. But what would this legality mean for the river and its surrounding communities in an Australian context? Is legal action enough? Or does it only serve to incorporate the natural world deeper into hostile frameworks of law and government?

As a white Australian artist and writer practising and profiting on stolen land, I was drawn to the complex issues addressed in this year’s Biennale. I spoke with Hannah Donnelly, a Wiradjuri curator and member of the Curatorium for ‘rīvus,’ to understand some of these conceptual and social concerns more deeply.

Ackroyd & Harvey, ‘Lille Madden / Tar-Ra (Dawes Point),’2022, seedling grass (fescue, native, rye), clay, hessian; image imprinted through process of photosynthesis, Gadigal land, Sydney // Photo by Document Photography

Kimberly Budd: Can you tell me about your personal practice and your current role as part of the Arts and Cultural Exchange in Parramatta?

Hannah Donnelly: I am a Wiradjuri producer and curator. I have been working as a producer and curator for a number of years, but I am someone who came through the experience of having my own creative practice, namely my writing practice. As a First Nations cultural practitioner, I’m always working collectively, both with the community and with First Nations artists. An artist doesn’t work in isolation. They’ll have a community that they might be working with, or they might be working with particular Elders or knowledge holders to tell a story through their work or to explore their concepts. Not to say that all First Nations practitioners are always working collectively, but I think it is often the way that we work with the community. And so this practice really lent itself to the process of working collectively with the Curatorium and the participants of the Biennale.

Casino Wake Up Time, ‘Slumber Party,’ 2022, four antique beds; Australian native plants (buchie rush, bullrush, bracken fern, lomandra, eucalyptus, grass), weeds (umbrella sedge, setaria), terracotta clay, jute string, paper wire twist ties, second hand denim pants, skirts and shorts // Photo by Document Photography

KB: From your perspective, what were some of the most important messages for the audience through the themes explored in the Biennale this year?

HD: It is about taking action around and responsibility for our water systems, both freshwater and saltwater. One really emotional moment where that message came across strongly for me is with, ‘Casino Wake Up Time,’ a weaving collective in Bundjalung Country. They revitalise specific regional weaving styles from Bundjalung. They are a group of Aunties, and a practitioner, Kylie Caldwell. They have woven an installation with abstract forms that looks at their freshwater systems. At the time of install, there were devastating floods in Bundjalung Country, in Lismore and the surrounding towns and areas. So some of the Aunties, whose weaving was in the exhibition, lost their homes there, lost everything. It was really incredibly devastating. The message for them in their work, ‘Slumber Party,’ was about waking up to the need to protect our fresh water systems, for individuals to not be disconnected from the water system that’s sustaining them where they live.

A lot of works in the exhibition are like that. They are not just signalling messages around protecting the environment, they reflect the real lived experiences of people that are going through this trauma in their environment. I hope for audiences to take away some of that need for action.

Casino Wake Up Time, detail from ‘Slumber Party,’ 2022, four antique beds; Australian native plants (buchie rush, bullrush, bracken fern, lomandra, eucalyptus, grass), weeds (umbrella sedge, setaria), terracotta clay, jute string, paper wire twist ties, second hand denim pants, skirts and shorts // Photo by Document Photography

KB: What is your opinion on the granting of personhood to rivers or other ecosystems for further protection? Is this legal action beneficial towards reparation in our settler/colonial nation building?

HD: There are definitely complexities there for First Nations communities in the idea of using Western legal systems to grant legal personhood for waterways and ancestral waters. There’s a term that Aboriginal water advocates in this country use, ‘cultural flows.’ One of those advocates, Bradley Moggridge, a Kamilaroi water scientist, was involved in some of the Biennale’s programs. There are also a lot of advocates for the Murray-Darling basin. The artist Uncle Badger Bates, who is in the exhibition, talks about the concept of Aboriginal water and that cultural flow means the value of water is not just about how it sustains an industry or how it sustains a population. For Aboriginal people, the value of water is connected to cultural and spiritual practices in addition to the social and economic outcomes. The idea of a river having legal personhood begs the question of who is the voice?

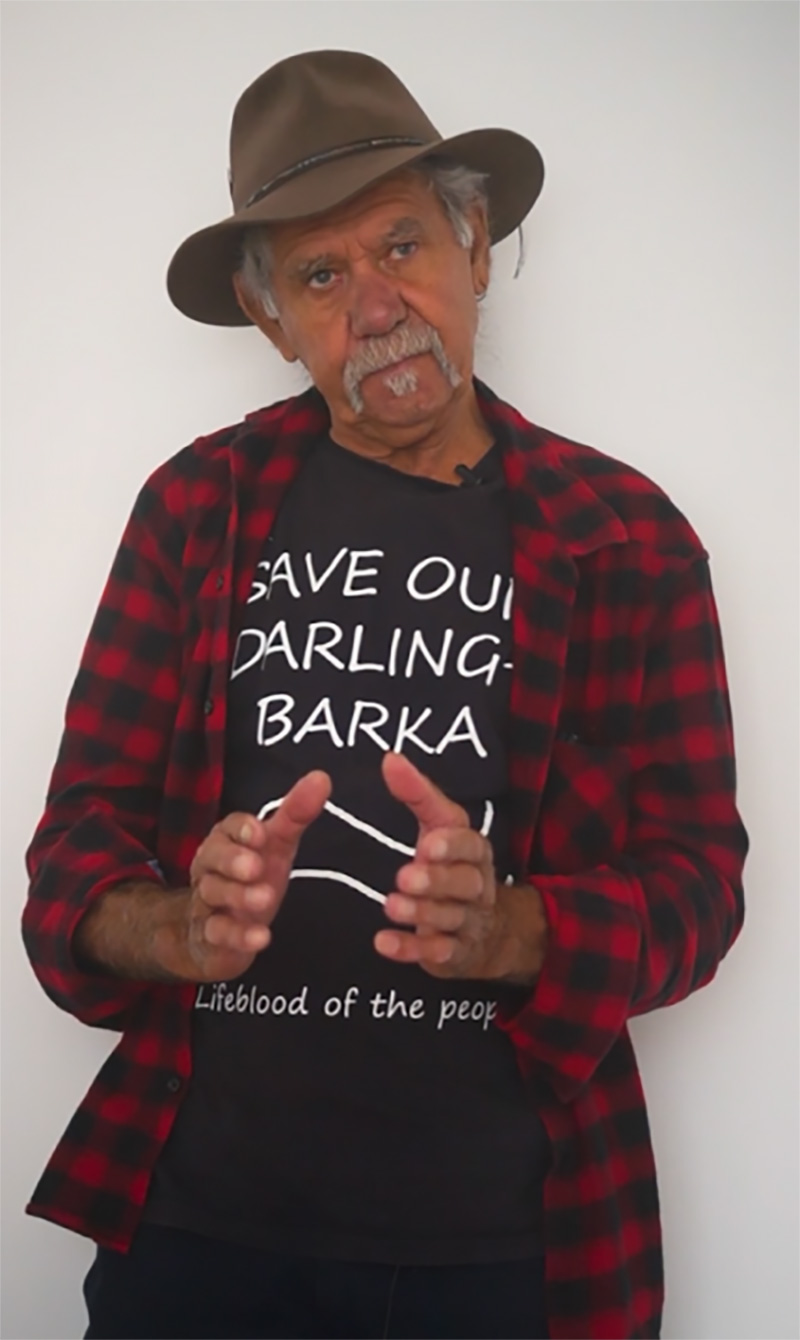

Voice of the Baaka river, (film still) 2022 Spoken by Badger Bates Barkandji Elder, from the Baaka river region, Australia, // Courtesy of 23rd Sydney Biennale

In the exhibition, we reflected on the voice component. We found the best way to think about how the voice of water, or a water system could be represented, would be to look at the people who were working closely with and advocating for that river or water system. In most cases it was a Custodian or a Traditional Owner. They would be able to speak to those ancestral spiritual connections, the social environment, politics and all that is bound up in that water system, for them and their community. It gets really complex when we have, in this country, and, I’m sure, in the international context, so many different ways of recognising Custodians and Traditional owners.

Here, we have a federal system and then a state-based system for what we would either call native title or land rights. It’s an incredibly complicated system that puts the burden of proof on Traditional Owners.

One of the [other] ‘River Voices’ participating in the Biennale was Dr Anne Poelina, who spoke for the Fitzroy river, the Mardoowarra. In her research, she talks about the concept of ancestral personhood instead of legal personhood and how that might better align with First Nations’ connection to and understanding of water. We’re just not quite there with the legal system to be able to recognize those complexities. I think Anne Poelina, in particular, and the group that she works with for the Fitzroy Council, advocates for custodians to develop a way that an individual community member living by a water system can commit to an agreement with that system that recognizes its ancestral personhood outside Western legal norms.

Exhibition Info

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Arts and Cultural Exchange, Barangaroo, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, National Art School in partnership with Artspace and Walsh Bay Arts Precinct including Pier 2/3

23rd Sydney Biennale

Exhibition: Mar. 13–Jun. 13, 2022

Free Admission

biennaleofsydney.art