by Lucia Longhi // Apr. 29, 2022

This article is part of our feature topic ‘Occupation.’

Kubra Khademi (1989) is an Afghan artist who moved to Paris in 2015 after receiving threats in response to a performance on violence against women that she staged in the center of Kabul. Situated between drawing, performance and painting, her artistic practice starts from a reflection on the conditions under which women live and expands to depict them as beings experiencing their lives, bodies and sexuality freely. In her drawings women are pictured “floating” against a white background. They explore their bodies in an exuberant and joyful way, expressing a playful form of resistance to the patriarchal order. However, for Kubra Khademi, a critique of patriarchy is only the starting point of her visual discourse, which ultimately aims to portray a free space for new ways of existing. Her art goes beyond an autobiographical narrative to also include traditions, legends and family stories that have formed a background of sisterhood and protection.

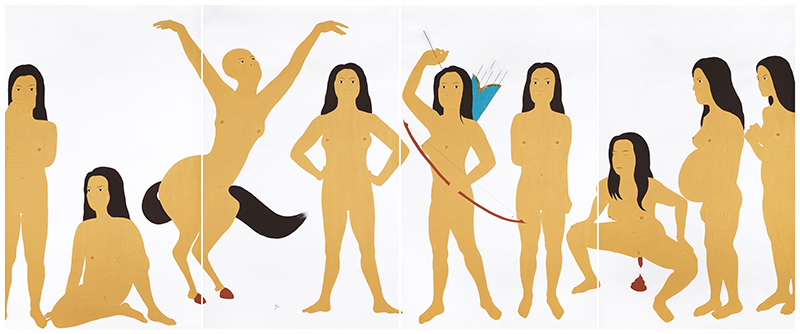

Kubra Khademi, ‘Premiere Ligne,’ 2021, gouache on paper, Quadriptyque, 4 x 250x114cm // Photo by Bertrand Hugues

Lucia Longhi: From which personal experiences, histories and traditions does your art originate? And why do you use visual art as a means to communicate your position against patriarchy and violence in Afghanistan?

Kubra Khademi: I have my culture and my past within me, I can’t run away from it. But most importantly, my culture is what I know best, so it appears naturally in my work. I grew up immersed in a very patriarchal society, in a very traditional family, but also in poetry and cultural tradition. So while my work stands against some elements of my culture, it is inevitably also permeated by them.

My artistic expression is not only about taking a stand against patriarchal hegemony, reclaiming my own existence, or even demanding equal rights for women. It is a reflection on women as such. That is why the women I draw are floating, somehow emotionless, without any anger. They exist, but where? I want to move away from the idea that Afghan women are defined solely by the burden of violence and focus on their entire way of existing, the many ways in which they have figured out how to live and survive.

LL: The topic of patriarchy is now even more pressing under the Taliban regime. How is the occupation of the Taliban reflected in the occupation of the female body?

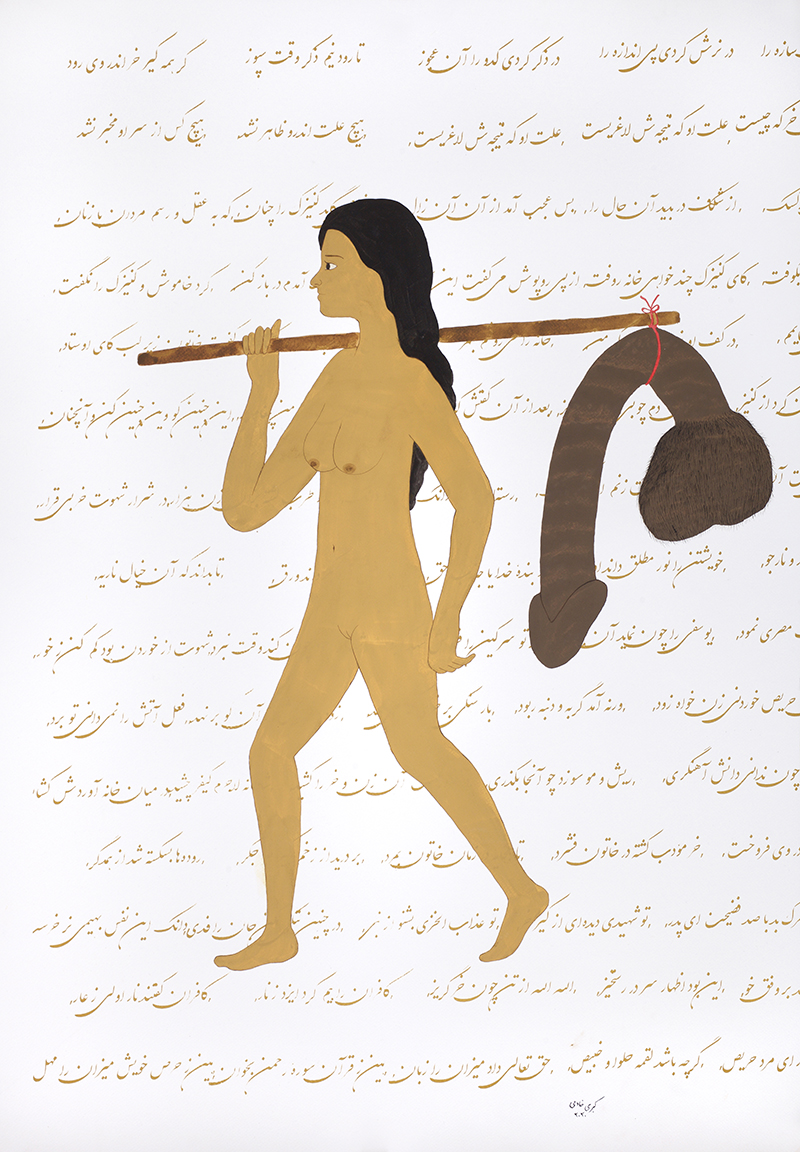

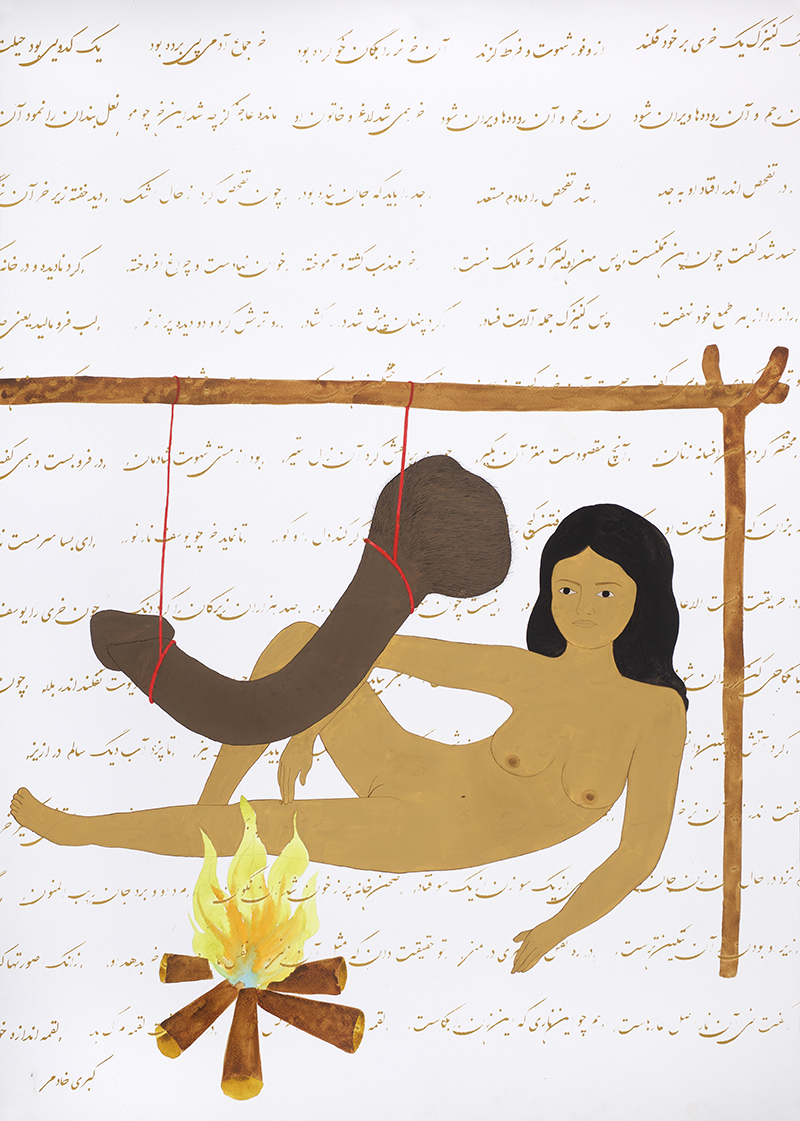

KK: Let me first make a distinction: patriarchy is one thing, the Taliban regime is another. The patriarchy I address in my work is the one embedded historically and traditionally in Afghan culture. The idea that men are superior to women derives from Islam, a religion that systematically controls every aspect of a woman’s life. I have experienced the different treatment of women’s and men’s bodies in my daily life since my childhood onwards, but I’ve always only drawn women. Why? Simply because I saw them a lot, and I saw them as more precious perhaps. In my drawings all the women are very visible, very exposed and shameless–they have to be visible. I don’t want to put clothes on them because my drawings are free and imaginative. They express all the force and freedom of these women. The most important thing for me is to bring out their sexual identity just as it is. This identity has to be exercised and recognized. Female sexuality is cursed in my culture. That’s why it appears in my work in a dominant way.

Kubra Khademi, ‘Bagage de route #1,’ 2021, gouache on paper, 100×57 cm // Photo by Bertrand Hugues

LL: Now that you live in Paris and travel to exhibit in the U.S., do you notice other forms of occupation of women’s lives in the so-called West?

KK: This is quite a hard question because I still feel new to the Western society. If I make a comparison with my country, this is absolute freedom! I can wear what I want, I am not obliged to get married and no one will judge me because I don’t have children. At the same time the criteria that define freedom keep changing for me, because freedom and equality are identified differently here. In the beginning I couldn’t even get the point about discrimination. Little by little I realized that I do come across situations of sexism here and I find it very dangerous because these men, they think they know a lot. So I learned that there is a form of patriarchy here, but it is not comparable to my country. Sometimes I can see inequality in workplaces where women are evidently more qualified than men but they still struggle in their job. Before coming here I thought Catholicism was a religion that respected women, but this is not true. The Catholic way of treating women reminds me of how Islam positions women.

Kubra Khademi, ‘Bagage de route #2,’ 2021, gouache on paper, 100×57 cm // Photo by Bertrand Hugues

LL: Feminism in your work manifests in a very expressive and direct way; it almost feels like a scream of joyful liberation. This form of feminism, in my opinion, has little to do with the cultural and social movements in Western countries.

KK: I am still learning what feminism is in Western society. The works by artists who define themselves as feminist are the ones to which I relate the most. But my work is personal; it is not dictated by a trend or other people or theories. Why? Because it is art which is an expression of myself. I have not had the historical, artistic, and theoretical references of Western culture. People often use the word “nudes” or “naked bodies” in reference to my drawings. I have never liked these terms, but I do not correct these people because they describe what they see and what they see is what they have been taught. To me, these bodies are just bodies: my body, my mom’s body, my sisters’ bodies, other womens’ bodies… The first drawing of women’s bodies I did was when I was 5 years old and I wasn’t inspired by any artwork, because I had never visited museums or seen any “nudes.” I had simply seen the naked bodies of women in the hammam. Of course, it was seen as wrong and my mom beat me up for it. I hid the drawing under the carpet.

Drawing a naked body for me is not a feminist act. Simply put, my body is my property. It is free because it is not oppressed by a man through marriage. It does what it wishes, and it wishes to be an artist. This is probably already a feminist statement.

Kubra Khademi, ‘The Warm War,’ 2019, gouache and gold on paper, 190×114,2cm // Photo by Bertrand Hugues

Portrait of Kubra Khademi by Celine Bouquett, 2021

LL:In what ways do you think art can help women to occupy physical and critical spaces for discussion?

KK: My works are playful and cheerful, because I want to imagine another reality that should have existed for these women.There is also a lot of joy in my personal history. In my family I have always been surrounded by positive energy from women. For example, they protected me when I was beaten by my brothers. My sister would come, and without saying anything she would get in the way and take the blows for me. In this way the pain was distributed over two bodies and I felt protected. These are manifestations of solidarity among women.

My drawings also express the freedom I felt when there were no men around. They are like a sense of liberation, like being able to breathe again. My hope is that future generations, when they see the work of someone like me, find a way to open a dialogue for change. I hope they can see a woman’s body in a new light, no longer as a place of sin and guilt, but as a playful and free space, where everyone can breathe freely.