by Nadia Egan // June 27, 2022

Taking the notion of repair as the foundation for ‘Still Present!,’ this year’s Berlin Biennale, Kader Attia set himself the task of addressing and proposing a means to heal the wounds of our society’s colonial past. Seeing art as a space to mend the lingering effects of oppression and control, artists from across the globe were invited to present works that manifested the task, as written in the curatorial statement, of “liberating our knowledge, thinking and actions from colonial patterns.” With such honourable words, the bar was set high.

João Gomes Polido: ‘Replica Song,’ 2022, installation view in KW Institute for Contemporary Art // Photo by Silke Briel

As a way of liberating our knowledge from these colonial patterns, history must arguably be rewritten to encompass those silenced by the many years of oppressive control. The narrative must be shifted and the pen assigned to the voice of those who have suffered most under colonial structures. Challenging the Portuguese folklore tainted by decades of nationalism and imperialist nostalgia, João Polido’s sound installation ‘Replica Song’ (2022) shifts the groundwork upon which folklore has been staged, offering instead an alternative account of the tradition that favours and acknowledges both the lived experience and its multilayered origins.

Asim Abdulaziz: ‘1941,’ 2021, video, color, sound, 4’43”, video still // © Asim Abdulaziz

Common contemporary thinking surrounding decolonisation centres our attention on future action, while often bypassing our present moment. Conscious of this mindset, Attia drew our attention to the voices of today that continue to suffer from wounds of both past and present. Taking Asim Abdulaziz’s short experimental film ‘1941’ (2021) as an example, knitters roam an abandoned Hindu temple in a hypnotic trance as their needles lock them into a “timeless present.” The film draws on the significance of knitting as an act of solidarity during WWII—an act that, according to Abdulaziz, seems nonsensical to contemporary Yemen. Yet through the repetitive, looping movement of hand and wool, the knitter becomes transfixed and distracted from speculating on past and future. Brought into the now by this meditative practice, the artist defies war’s capacity to claim agency over time and self.

Mónica de Miranda: ‘Path to the Stars,’ 2022, installation view in KW Institute for Contemporary Art // Photo by Silke Briel

Binta Diaw: ‘Dïà s p o r a,’ 2021/22, installation view in KW Institute for Contemporary Art // Photo by Silke Briel

Returning to the motif of repair—if we can call it that—glimpses of this hopeful intent were sadly only peppered among works on an ad hoc basis. Only a few pieces such as Mónica de Miranda’s poetic ‘Path to the Stars’ (2022), a beautiful intertwinement of personal and collective memories that foresee the relationship between humans and nature as possible sources of healing, or Binta Diaw’s large-scale hair weavings of ‘Dïà s p o r a’ (2021-22) that hold the flourishing seeds of former plantations; their sprouting symbolic a long-standing desire to heal, offered a momentary glimpse of hope among an otherwise sombre mood. While mournful in tone, the four-channel video ‘The Specter of Ancestors Becoming’ (2019)—one of two deeply atmospheric video installations by Tuấn Andrew Nguyễn—suggests the therapeutic and healing potential of storytelling, as Senegalese-Vietnamese families chronicle the intergenerational scars left behind from French colonial traumas.

Tuấn Andrew Nguyễn: ‘The Specter of Ancestors Becoming,’ 2019, installtion view in Hamburger Bahnhof – Museum für Gegenwart // Photo by Laura Fiorio

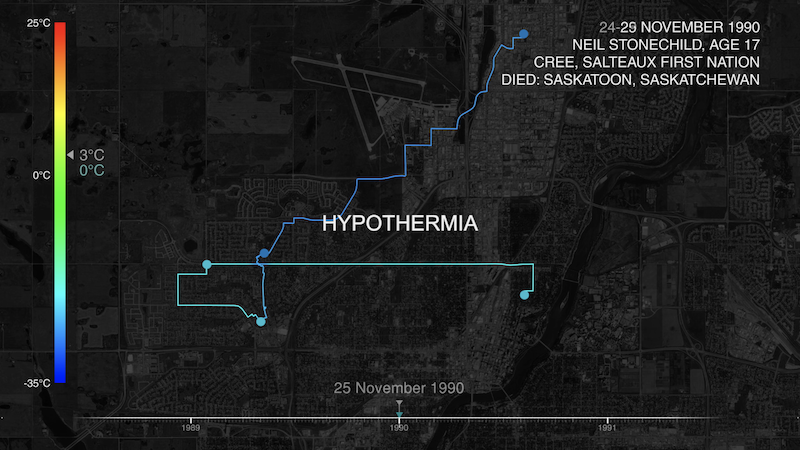

While the curatorial concept may have been lacking in terms of materialisation, it would be unfair to convey the impression that the biennale was short on talent or ability to leave a lasting impression—take Jean-Jacque Lebel’s ‘Poison Soluable: Scènes de l’Occupation Américaine à Bagdad’ (2013), a labyrinthine structure made of the now notorious blown-up images graphically documenting the rape, torture and humiliation of Saddam Hussein’s followers at the hands of uniformed US military and CIA operatives in Abu Ghraib. Another example is Susan Schuppli’s ‘Freezing Deaths & Abandonment across Canada’ (2021-22), a documentary-like video installation exposing the so-called “starlight tours”—an inhumane practice of taking Indigenous people into custody and then dropping them off into freezing, remote areas, with abandonment often leading to death by hypothermia. In both cases, an overwhelming shock value lingered long after.

Susan Schuppli: ‘Freezing Deaths & Abandonment across Canada,’ 2021-22, video, color, sound, 31’55”, video still // © Susan Schuppli

Susan Schuppli: ‘Freezing Deaths & Abandonment across Canada,’ 2021-22, video, color, sound, 31’55”, video still // © Susan Schuppli

Our thinking, knowledge and actions may not have been liberated from the patterns of colonialism, but the collection of works in this year’s biennale undoubtedly cast light on the treacherous consequences of colonialism that persist today while simultaneously illuminating the voices and stories of those too often cast in shadow. In Attia’s curatorial statement, he questions his motives for adding another exhibition to a world already saturated in material excesses. Yet taking steps towards the rehabilitation of colonialism’s destructive past can never be cast as redundant or amount to excess. While missing the mark on tangible proposals for repair, this year’s biennale undeniably confronts colonialism head on in a definitive act of resistance.

Exhibition Info

12th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art

‘Still Present!’

Akademie der Künste, Dekoloniale Erinnerungskulture in der Stadt, Hamburger Bahnhof, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Stasi Zentrale – Campus für Demokratie

Exhibition: June 11–Sept. 18, 2022

Admission: € 18 (reduced € 9)

12.berlinbiennale.de