by Bentley Brown // July 21, 2022

Visual artist, poet, former lead singer and founding member of the seminal Krautrock band CAN Malcolm Mooney’s solo exhibition, ‘Works: 1970–1986,’ focuses on the artist’s geometric grid-like explorations between 1970-1986. Shown alongside drawings and a variety of archive material in Ulrik’s recently opened Chelsea gallery, these works range from the highly detailed and intricate matrices of ‘Package’ (1987) to the flurry of movement arranged in rows of color in ‘Green Harlem Angel’ (1972), a set design for a never staged play, to, finally, “the absence,” or Black re-imagination of the grid, in ‘The Abyss, Space in the Night’ (1974). In addition to the exhibition’s focus on Mooney’s interest in the grid as a structure, ‘Works’ also cues the viewer into the artist’s repositioning of the grid as a “maximalist” site where rhythm is abundant. This approach places Mooney at odds with traditional narratives of minimalism that have seen the grid as the darling of “purity,” “order,” and art as an interaction between the viewer and “space.” Instead of portraying these old predilections of “the grid” as reflections of “space,” he shows them to be constrictions of “place.” Rhythm, on the other hand, can open a capacity for space, an interest that took Mooney from the center of avant-garde rock n’ roll to the avant-garde in contemporary art all in the same stroke.

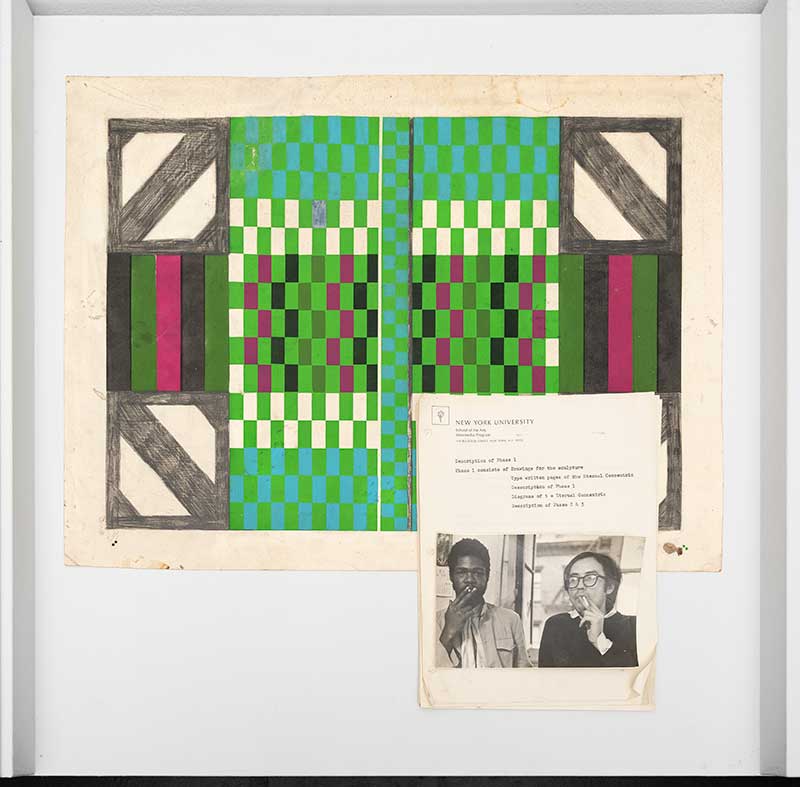

Malcolm Mooney: ‘Green Harlem Angel,’ 1972, mixed media on paper, photograph of Serge Tcherepnin and Malcolm Mooney at Morton Subotnick’s Intermedia Program, NYU. Pages from Malcolm Mooney’s proposal for the Eternal Cancentric, sound sculpture project and kente patterned tile installation, NYU, 1972 // Photo by Stephen Faught, courtesy of the Artist and Ulrik, New York

In ‘Package,’ the centralization of the twilight zone between the plasticity of a stroke of red and its enigmatic shadow abstracts and transform allusions to Georgio di Chirico’s eerie pre-surrealist scenes of Italian towns, such as ‘The Enigma of the Day’ (1914), into jazz. Meanwhile, in ‘Green Harlem Angel,’ Mooney inserts Pan-African black, red, and green into what would otherwise be a chromatic grid of slight variations of green. In this collision of the colorful (represented by the Pan-African flag) and the colorless (seen in the breached structure), a melody of beauty and tension that reflects the color-filled Black “angelics” of Mooney’s title is born. ‘The Abyss’ presents an expanded black textural surface in which only a peephole and some spillage on the right-hand side provide windows into the blue and grey grid that once was or exists in spite of. Yet this “abyss” is not absent of color. Expressive borders of red with green polka dots, a vertical block of rugged green, and an emergence of white line the outskirts of the black space. The potency of this work lies within the nature of the abyss which Mooney echoed on the 1989 CAN track “Below this Level.” “Below this level, there is none,” repeats Mooney, followed by a common, instinctual, reaction to falling: “ahhhhh ahhhh ahhhh ah ah.” Mooney’s recollection of what it’s like “to enter into where no one wants to be”, “the abyss”, is at once horrifying, hypnotic, blissful, and ultimately freeing.

Malcolm Mooney: ‘The Abyss, Space in the Night,’ 1974, oil on canvas, 137.2 x 111.8 cm // Photo by Stephen Faught, courtesy of the Artist and Ulrik, New York

Malcolm Mooney: Installation view at Ulrik NYC, 2022 // Photo by Stephen Faught, courtesy of the Artist and Ulrik, New York

“Malcolm pushed us into a rhythm,” once said CAN bassist and bandmate Holger Czukay. This statement describes what Mooney brought to the Cologne-based band, who, in 1968, were amidst a search for musical direction. Rhythm “pushed” CAN out of cookie-cutter European pop-rock and the constraints of the contemporary avant-garde into exploratory polyrhythmic space via the blues and Black aesthetics. The statement also sheds light on Mooney’s intervention into “the grid” as one of rhythm. Through rhythm, the artist exposed the fragility of structure when confronted by the “worrying note of Black aesthetics,” a turn-of-phrase describing how a musical note is exaggerated for the purposes of expression. Central to the “worried note” is its relationship to “the Music,” a term used interchangeably with “Black music” so as to include the Afro-diasporic lineage, the importance of “feeling,” and to avoid reducing Black musical production to the political connotations the term “Black” can imply when used by agents outside of the community. The worrying note is the life force that allows “the Music” to continuously evade a singular definition and structure.

Malcolm Mooney: ‘Package,’ 1986, oil on canvas, 121.9×182.9 cm // Photo by Stephen Faught, courtesy of the Artist and Ulrik, New York

Mooney’s predilection for “maximalism” and interdisciplinary exploration was cultivated in the SoHo, Manhattan, art movement, where he became a central figure following his return to the United States in 1970. At this time, Mooney, an artistic Jack-of-all-trades, or “Mastr” of all (to use Kerry James Marshall’s “misspelling”), simultaneously engaged painting, poetry, music, printmaking (a skill he learned working in his father’s print shop in Yonkers, NY), theatrical performance and dance. In doing so, Mooney traversed the exciting possibility of the pluralist downtown New York art scene of the 1970s alongside visual artists such as Frederick J. Brown, Ed Clark, Danny LaRue Johnson, Virginia Jaramillo; musicians Ornette Coleman, James Jordan, Henry Threadgill, Joseph Jarmon; and fellow multidisciplinary artists Sara Penn, Claude Lawerence, Felipe Luciano, Jean-Claude Samuel, to name just a few. Within this milieu, Mooney, alongside Brown, formed the 120 Wooster Street collective (participants listed above), which, along with the wider SoHo community, provided an open-source palette of support that aesthetically did not lock one into place (a traditional grid). Instead, it provided open space in which “the grid” of what or how one was supposed to create became worried, transforming art-making into a game-board of possibly, into a million ways to say, as Mooney did in a 2012 interview with Jan Verwoert, “I CAN.”

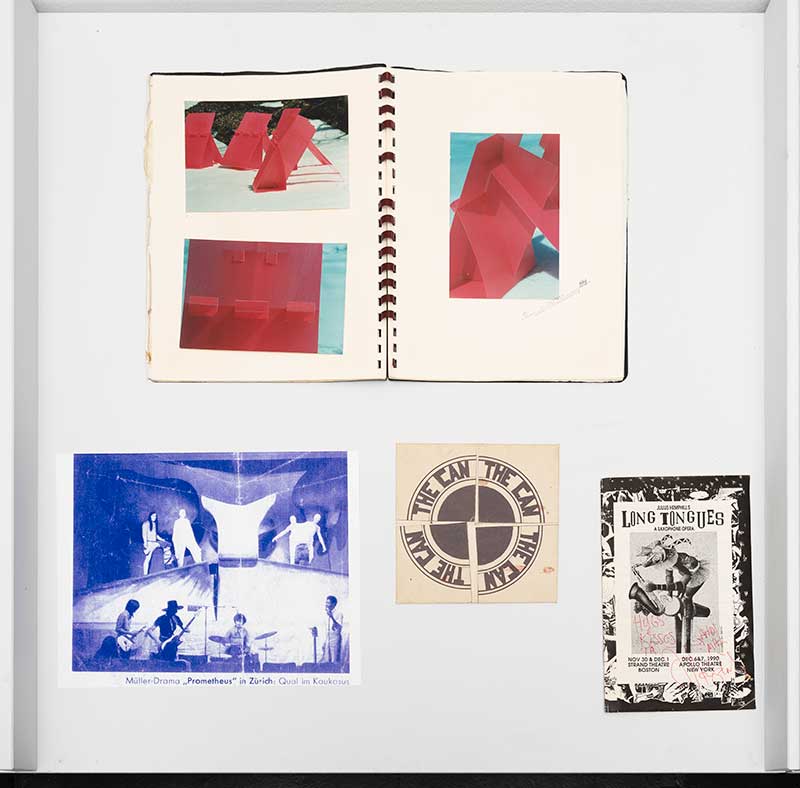

Plastic music stands, designed and built by Malcolm Mooney and commissioned by Julius Hemphill, 1994, photographed by Malcolm Mooney. Julius Hemphill Long Tongues Saxophone Opera Program. CAN, 1969, Schauspielhaus, Zurich, Switzerland, production of Prometheus Unbound, directed by Heiner Müller. Program for CAN Opera, 1969, designed by Malcolm Mooney and Francois Ryser // Photo by Stephen Faught, courtesy of the Artist and Ulrik, New York

This worrying note, as revealed in Mooney’s grids, is the affective proximity between “Structure” and the necessary delinquency that takes place inside of, or (in the case of ‘The Abyss’) in spite of “Structure.” The grid produces rhythm—sound, feeling, and spirit that meets at the intersections where moments turn. ‘Works’ rightfully positions Mooney as a pioneer of Maximalism and demonstrates his use of visual, sonic, literary, and performative modes of expression—rhythm—in the spirit of a trajectory of feeling. This feeling is the sublime freedom of discovery, or, as Mooney put it in his unpublished poem ‘We Rode into SoHo’ (1990) the space to “just play man… play.”

Exhibition Info

Ulrik

Malcolm Mooney: ‘Works: 1970–1986’

Exhibition: May 26–July 9, 2022

ulrik.nyc

453 W 17th St #4NE, New York, NY 10011, click here for map