by Dagmara Genda // July 29 2022

This article is part of our feature topic ‘Slow.’

What does it mean to “do nothing” and why should we even ask ourselves this question? Is doing nothing an activity in its own right, and if so, what does it mean to think of it as an art practice? These are some of the questions Canadian artist Victoria Stanton has been posing herself over the past six years, two of which have taken place in a Ph.D. programme at Concordia University in Montréal. Known primarily for her almost three decade long performance practice, she also works as a researcher, curator, educator and academic. Though the roles feed into and influence one another, they also have kept Stanton busy enough to reach a moment of near burn-out in 2016. At that point, she realised she needed to rethink her unquestioned drive to produce and consider new ways of working.

Victoria Stanton: ‘Seven Minutes in Heaven,’ 2017, Cabaret Su’l’perron de Zone d’affluence, Mercier, QC, Canada // Photo by Cindy Doucet

Many of Stanton’s performative works can be understood as infiltrations that interrupt or somehow reconfigure commonplace situations. ‘Cooking in Reverse’ (2018), for example, was a performance in Copenhagen where Stanton accompanied participants to supermarkets and then, according to their directions, cooked them their favourite meals. In ‘Seven Minutes in Heaven’ (2017), the artist challenged her audience to make sure her feet did not touch the ground for seven minutes. Her work has thus always been somewhat ephemeral, sometimes even private, though her focus on slowness, says the artist, has “distilled” her work even more. Here, she talks to us about why “doing nothing” is necessary, how it can be a subversive act and how it ties into traditional performative concerns with “presence.”

Dagmara Genda: What happened that in May 2016 you decided to explore “doing nothing” as an artistic practice?

Victoria Stanton: There were a number of “unofficial” starts prior to that. The most salient of these happened two years earlier. After a very intensive cycle of projects spilling into other projects, for which, of course, I was and remain extremely grateful, I was completely wiped out. An artist-run centre in Montréal put out a call for works to happen in their storefront and I really wanted to submit something despite the fact I was so exhausted. Then I thought, “where is this urgent need to apply coming from?” After which I realised, I just wanted to be in the gallery and have a holiday. So I decided to propose the space as one of open free time geared toward relaxation.

Victoria Stanton: ‘Resting, Walking, Place-Making: the invisible, liminal spaces in art’ (2018), as part of the P. Lantz Artist-in-Residence program, McGill University, Montréal, QC // Photo courtesy of the artist

In my proposal I wrote that though the project would likely be rejected, I hoped it would generate discussion, because I was sure that I was not the only one feeling this way. Sure enough, they sent me a very kind letter saying, “Yes you are right, we did not accept it, but it did generate discussion and we wish you a lot of luck with your work.”

Two years later, I saw a call for another space in Montréal, and the timing felt right so I applied. This time it was accepted.

DG: What did the project look like when it was finally accepted?

VS: In what is a growing trend, this was an artist-run centre working without a fixed location. So the work was an infiltrating performance into the social and architectural fabric. The project went on from May 2016-2017.

DG: The beginning of COVID is when you started your Ph.D. Are the two connected?

VS: Yes, but I was accepted into the programme before COVID started. I knew a Ph.D. programme could be a good context for the project, because it would provide me with structure and resources, both within and beyond the university. I began the Ph.D. four months after COVID started. I am also doing the programme at half speed.

Victoria Stanton: ‘res(is)ting // repos comme résistance,’ 2021, Verticale – centre d’artistes, Laval, QC // Photo courtesy of the Artist

DG: Academia has a “publish or perish” reputation that burns many people out. Do you just negotiate that by working half-time?

VS: I never had designs on becoming a tenured professor, so that lets me work more slowly. I am investing some of that time into other activities at the university, like the ‘Slowness and the Institution’ or the ‘Pedagogy and Time’ series with my colleague Stacey Cann in our collective The Bureau of Noncompetitive Research. These series of events and conversations have allowed us to move beyond our faculty and invite international guests, like artist Robert Luzar from Bath Spa University in Bath, UK, for example.

What is meaningful for me is finding co-workers and allies who are interested in slowing down and not competing, though at the end of the day, of course, we are competing for the same money from the same funders. Nevertheless, we try to foster a non-competitive attitude and support each other as much as possible. I want to establish places of meaning-making and nurture the observation practices that come with doing things more slowly.

DG: How is that documented and disseminated to the public?

VS: Writing remains an important foundation for how I have been transmitting my work. Maybe I will end up leaning into publication and photography, perhaps audio recording, but these media are not calling out to me as something that I can craft and work with. I do not have a sense of a product in this work.

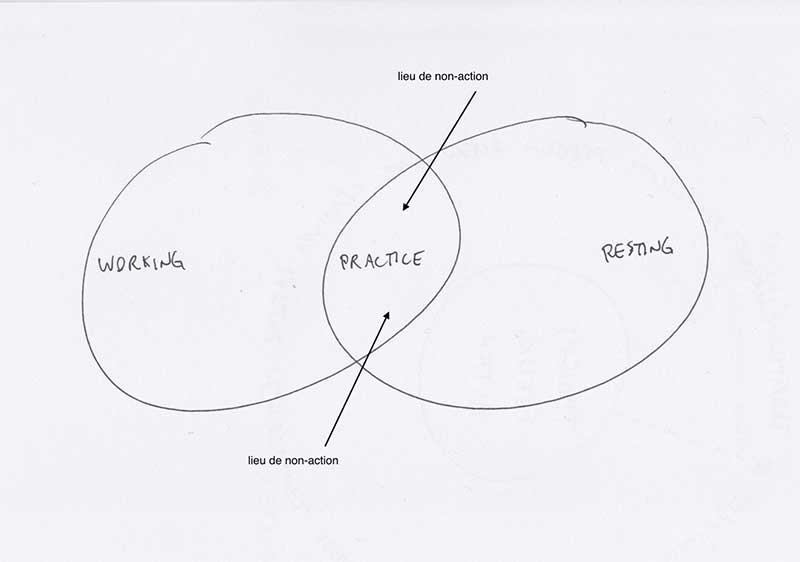

Victoria Stanton: Schematic for the publication ‘res(is)ting // repos comme résistance,’ 2021, Verticale – centre d’artistes, Laval, QC // Courtesy of the Artist

There is a school of thought that performance cannot be documented. We can only experience performance through re-enactment. What if this notion of not documenting challenges the capitalist, neo-liberal framework of how we are expected to produce and the purposes for production? What if I can resist these pressures, not through the project itself, but through the outcomes? The university context allows me to think through these questions and not answer them immediately or quickly.

DG: Could it also be a critique of conservation and preservation in the art world?

VS: What if the whole conservation process is a colonial enterprise? There is an Indigenous artist and researcher named Dylan Robinson, who put out a book, ‘Hungry Listening,’ in which he writes about the colonial practice of audio recording. While we preserve and make recordings available for future generations, he asks “whose story is this to tell?” He also presented a talk in which he expanded this question into natural history museums, specifically in reference to indigenous masks stored in drawers, climate protected, and displayed behind glass. He exclaimed, “those masks are my ancestors and my ancestors never stopped working!” Normally, these masks could disintegrate. Sometimes there are rituals where they are burned. Like everything else, they have their life cycle and then they get to rest. But now his ancestors are not allowed to stop working.

This story resonates with me. How can I, from my position and heritage, be thinking about that too? What does it mean for my practice as an artist? Am I doomed to be participating in the colonial project?

Victoria Stanton: ‘A Short Presentation About Nothing,’ 2017,The Mile End Poets’ Festival, Montréal, QC

DG: What is the benefit of framing “doing nothing” as an art practice, rather than a spiritual practice or simply hanging out?

VS: One of the benefits is that it provides the opportunity to have these kinds of conversations with cultural workers. The RCAAQ, an advocacy organisation for Quebec’s artist-run centres, had a conference in which they acknowledged the need to slow down. They invited me to conduct a session with them.

DG: Did the RCAAQ put policies or suggestions in place that will help them slow down?

VS: This meeting only happened a few months ago. They are now making a written document about it for their community, so that they can think about how to tackle this challenge.

I met a centre at this conference with whom I will work with in the future. I said that I wanted to bring them into my project without making it feel like it is more work for them. In response they told me that they have already been having discussions about how to communicate their limits and boundaries with invited artists. They had never talked about this with the artists before!

This is also an issue with our funders. They ask ridiculous things from the artist-run centre directors—the paper-work, the amount of programming, the statistics.

Victoria Stanton: ‘A Short Presentation About Nothing,’ 2017, The Mile End Poets’ Festival, Montréal, QC

DG: Let’s go back to the infiltration pieces: who are the people coming to participate? In Montréal, I can imagine you already have a community and know many people who come to the performances, but you did a project in Finland. What was that like?

VS: This was a festival in which they programmed pieces in public places where many people circulate. So all kinds of people stopped by. This can happen in Montréal too. But on the question of sitting quietly, in Finland, people very naturally fall into silence. It’s part of the culture there. Here, less so.

When I first did these events in Montréal, I encouraged people to be quiet together. But when doing them again shortly after the lockdowns, people needed to talk! And I didn’t want to stop that. Nevertheless, this wasn’t a party, so people were there for different reasons and could and did do different things. So there could be a few people talking, but over there is someone contemplating the water, and next to me is someone reading a book.

DG: So the art context also gives permission to act in different ways. You can’t just pull out your book at a party. It would be rude.

VS: Yes, in an art context, doing nothing can also be social.

Victoria Stanton: ‘Roadside Attractions,’ 2010, ‘Spatializing the Local,’ Teatro Arka, Assemini, Sardinia, Italy // Photo by Christian Richer

DG: So what does it mean to package it and make it “something?”

VS: In some ways this has always been a part of my practice but not articulated in terms of “slowing down.” I am ultimately interested in “presence” in performance practice and art-making. This includes my awareness of the audience’s presence and the audience’s awareness of its own presence. This led to very quiet work, work where nothing happened.

Nevertheless, something did happen. I see “non-action” as being on the spectrum of action. Stillness does something. The type of perception I want to foster is the noticing of the noticing itself. So this is not just downtime, it is about cultivating an attitude of rest.