by Dagmara Genda, photos by Ryan Molnar // Aug. 9, 2022

Monira Al Qadiri was seven years old during the Gulf War when Iraq, in 1990, annexed Kuwait in just two days. The US-led response resulted in a military conflict that lasted into March 1991. It produced some of the most iconic images through which much of the world was introduced to Kuwait at that time: seared black landscapes with towers of flames launching into the smoky air. Al Qadiri remembers these scenes of oil well fires, though, as a child, she could not grasp the danger of the situation. For her, this was an exciting time when she was allowed to stay home from school. Food shortages meant being allowed to eat chips all day, bombs were fireworks and a frenzied escape from place to place was a mysterious adventure. For her, it was a moment of intense creativity. “When you’re a kid,” she says, “you can make anything amazing and beautiful.”

In 2013 Al Qadiri made a video, ‘Behind the Sun,’ about this experience. Video footage of the fires was juxtaposed with audio monologues from Islamic television programs of the time. Over billowing red flame, one subtitle reads, “…it rivalled the beauty of roses.” Her older sister and family have a different relationship to this difficult past. Some of them no longer want to talk about it, but Al Qadiri has made it, or rather its black viscous source, the centre of her art practice. Oil and its products, its aesthetics and its culture inform the artist’s practice, though she makes it clear that she also draws on pre-oil histories and is motivated by hope for a post-oil future. A trademark of her oeuvre are resplendently iridescent sculptures that look like crowns or ancient temples. She has produced them in different sizes, from small models that sit on a table top to three-metre tall public monuments. They are most often made of a light plastic—a product of the very oil industry she critiques through her work. In her case, the plastic is a biodegradable sort, though she does not entertain illusions that her gesture will make a difference in an industry far bigger than her art could ever be. The people she most hopes to reach are those who have remained in Kuwait, a country completely dependent on its oil revenue and living recklessly without a plan B.

“In Europe, people see oil through the lens of ecology, energy and environment,” she explains as we stand in front of a sprawling model of an oil refinery that will be shipped to Texas for a show at the Blaffer Art Museum in Houston opening on September 24. “But in Kuwait,” she continues, “it is taboo to talk about oil. Many people see the oil industry as a kind of benevolent genie that makes everyone rich.” She recalls an artist talk she held in Kuwait about ten years ago, in which she talked about oil, its consequences and how she deals with it in her art. “I talked about nothing but oil for two hours but afterwards a newspaper reported that I just did a lecture on art history and my favourite colours!” She explodes into a laugh. Laughter often punctuates our conversation even as she retells anecdotes of tragedy. Rather than a response to humour, it feels like the sort of reaction in the face of absurdity, a sometimes hopeless shuddering of the body and perhaps a method of coping.

Though the artist puts on a happy face, the “aesthetics of sadness” has played a role in her life and practice. “Sadness has a kind of nobility in our culture,” she explains. “In Europe it is seen as a disease that has to be got over.” Sadness is present in the literature and songs of the Middle East, in the howling sea shanties, called “Fijiri,” of the men on pearl diving expeditions. Her grandfather, of whom only one photograph exists, worked as a singer on such an expedition. The hunt for pearls was the dominant industry in coastal Arab countries before oil was discovered. It was a dangerous profession in which many divers suffered from malnutrition, with some dying from attacks by swordfish and sharks, or simply drowning. In order to endure their work, a singer would always come along for the journey. The divers, banging on pots and pans, would constitute his band. The songs exist to this day though the modern versions are somewhat melodic and pleasant. The originals, existing in rare recordings from the 20s and 30s, were more like growling and guttural screeching—as if an embodiment of the sheer stress the divers had to endure.

Al Qadiri’s iridescent palette references this history of pearl diving, but the sheen is also reminiscent of oil, slicks of which would stain the water of her childhood beaches. Oblivious, she and her friends would swim through the swirling greasy rainbows anyway. The seduction of an industry that threatens to spell the end of her homeland is the contradictory thread weaving through all of Al Qadiri’s work. On August 4th, the artist unveiled a new public art sculpture on the bank of the Thames. ‘Devonian’ makes reference to the organisms which, over 400 million years ago, were compressed within the earth to eventually turn into oil. The name comes from Devon, England, where fossils of these creatures were first found in the region’s red sandstone and later studied. In her sculpture, Al Qadiri attempts to crystallise the moment oil was formed by animating the bodies of these extraterrestrial-looking creatures with iridescent colours to produce a pearly, oil-like sheen.

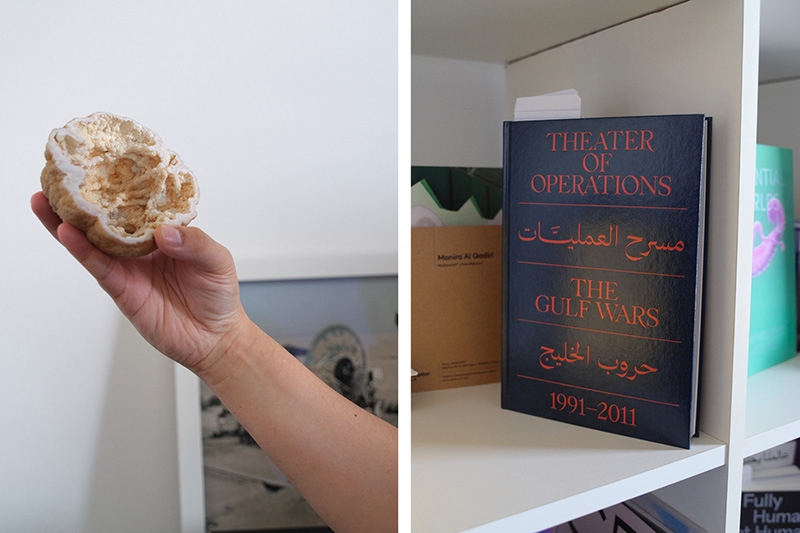

For the Blaffer Art Museum, Al Qadiri is building robotic arms based on designs for oil drills. They will be animated with moving fingers, though during our visit they sit still on a table in her studio. Their mysterious, other-worldly aesthetic is testament to the secrecy of the oil industry. Though we all use and profit from oil, the minority of us knows anything about what the extraction process looks like. This included, and to some extent still includes, Al Qadiri. Though she built a model of a refinery and has been making oil drills as sculptures, she has never seen one in real life, nor has she entered a refinery. She is baffled by the opacity of an industry whose products not only fuel our cars, planes and heat our homes, but are in our moisturisers, shampoos and clothing. When she started researching the drills, she was shocked by how ornate and beautiful they were. Drills are often gold-coloured and encrusted with diamonds. “They really look like jewellery!” she exclaims. As part of her on-going research, the artist collects trade magazines, manuals and watches the industry’s Hollywood-quality trailers introducing the latest in drilling technology.

Currently she is part of a show organised by Berlin’s Reference Festival called ‘SUPERFUTURES,’ curated by Agnes Gryczkowska at the luxury department store Selfridges in London. Al Qadiri is showing a giant globular inflatable sculpture, ‘Benzene Float’ (2022), based on the shape of molecules for benzene and propane. This show was the first that a large contingent of her family came to see, but for relatively unexpected reasons. “Selfridges is like the second holy place of the Gulfies,” laughs Al Qadiri. “For my extended family, this is more important than the MoMA!” Though her parents have always been acutely aware of Kuwait’s apocalyptic course, others remain in a state of denial. But now, in Selfridges of all places, she can talk to them about more than her “favourite colours and art history,” as the one newspaper once put it. The location of the show is thus ironically fortuitous. Thousands of miles away from Kuwait, her work might reach the audience whom she sought to address back home.