by Anna Roos van Wijngaarden // Aug. 29, 2022

This article is part of our feature topic ‘SLOW.’

Slow practices, often underpinned by concerns about sustainability, are gaining appreciation in the arts. Among them is biotech, which takes place, first and foremost, in the laboratory rather than the gallery. Nevertheless, there is an undeniable artistry to this science, whose creativity lies in biofabrication and the associated questions raised about the relationships between humans and nature. Is biotech a signal of innovative progress or a measure of the anthropogenic domination of the natural world? What does it look like as an art practice? The technologies behind biotech move at lightning speed, but after the design phase, the creator must patiently wait for the natural process to finish itself.

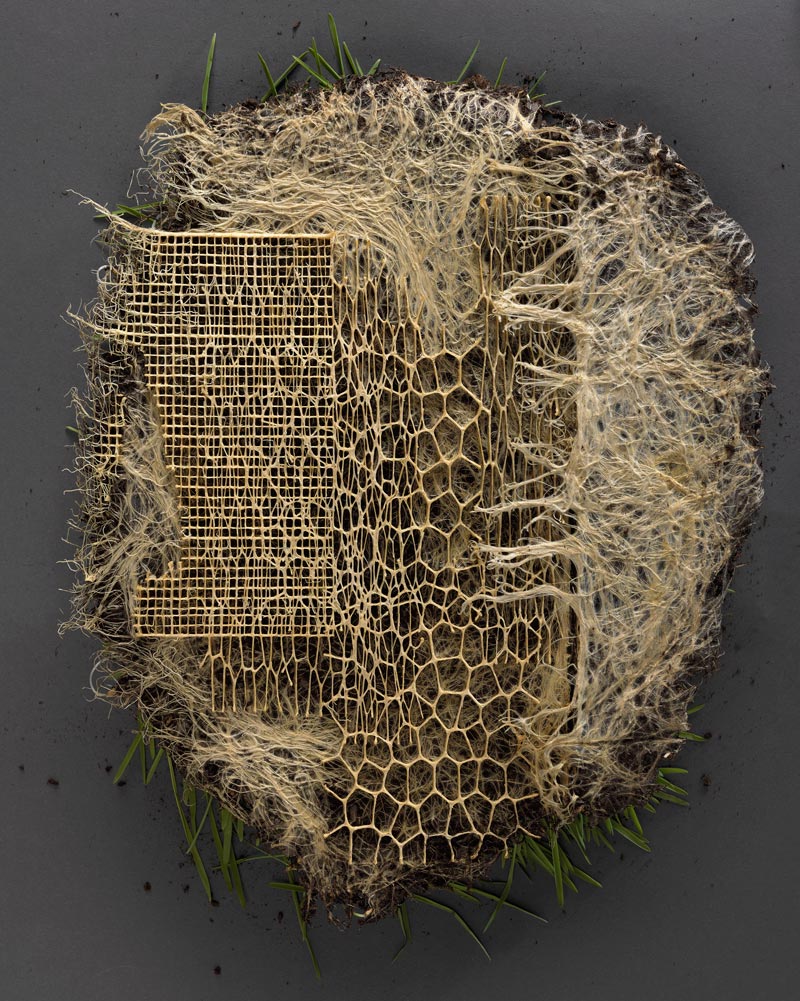

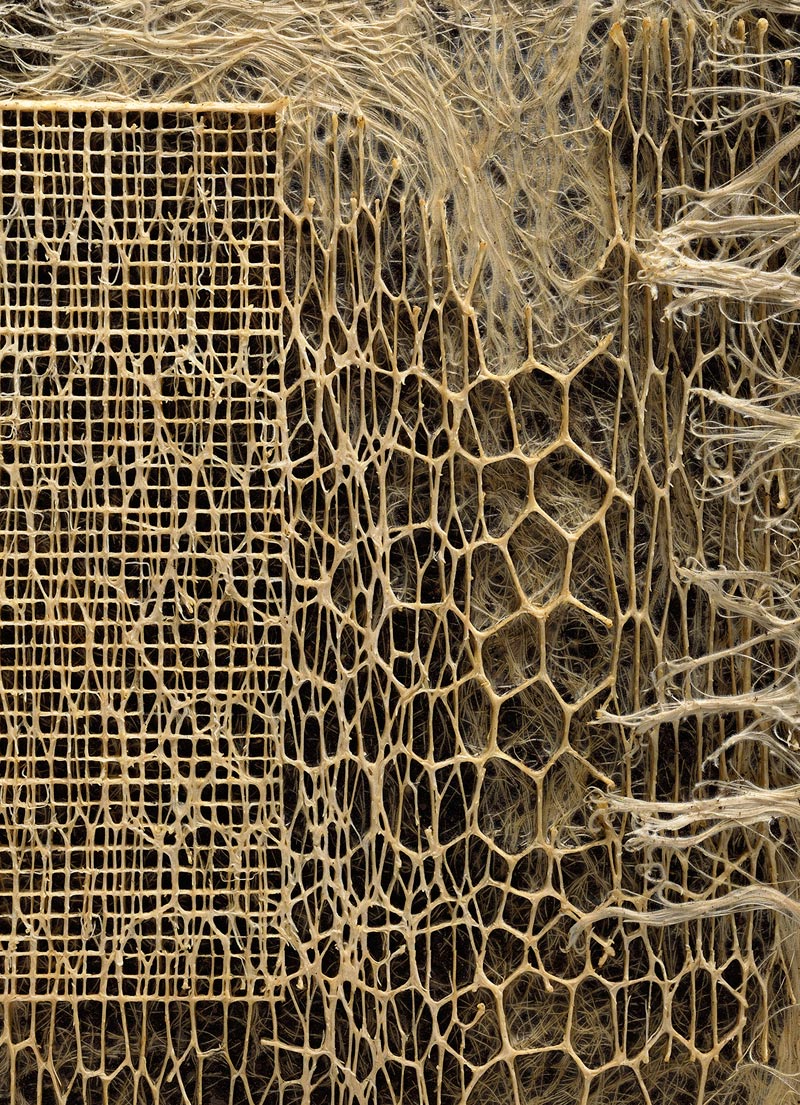

Diana Scherer: ‘Entanglement,’ 2022, 23rd Sydney Biennale, grown floorpiece, soil, seed, roots, 350×350 cm // Photo courtesy of the artist

One of the pioneers in biotech art is Diana Scherer, a German researcher and sculptor who lived in Amsterdam for over 20 years. At the core of her botanical installations, textiles and photography lies a great admiration for and curiosity about what neurobiologists call “the brain of plants.” The artist studies plants and root systems so as to control their “natural” growth processes. In her studio she creates artificial biotopes to grow her root art using soil, seeds, light and subterranean templates from both natural and man-made patterns. The roots follow these patterns and from there on, the work grows itself.

Her latest commission for the 23rd Biennale of Sydney, ‘Entanglement’ (2022), explores xylem vessels, the critical tissue responsible for transportation of water through plants. We talked to Scherer about her slow “collaboration with nature” and how it intersects with science, ecology, and sculpture.

Diana Scherer: ‘Entanglement,’ 2022, Sydney Biennale, grown floorpiece, soil, seed, roots, 350×350 cm // Photo courtesy of the artist

Anna Roos van Wijngaarden: The pace of your practice is dictated by how fast the plant you work with grows. How do you negotiate time when there are deadlines?

Diana Scherer: There are tasks where I know exactly what to do to create a certain outcome: what template to use, how to adapt the light and timing for different seasons. I have these rules in my head because I have experience. But it’s true that I’m often dependent on the speed of the work and that gives me what I call “growth stress.” For example, I’ll take part in an exhibition in Rotterdam at the end of September. In July, it all seemed to go wrong; it didn’t grow the way I wanted, it was too humid, and there were fungi that I couldn’t control. It’s physically quite hard work and everything goes slowly. That is challenging and I often don’t know what a piece will look like.

On the other hand, surrendering control is part of the beauty of the work. If I design a clean template and the result doesn’t turn out the way I expected, that can be disappointing. But sometimes I don’t expect much and end up with a crazy thing that looks surprisingly good. It all comes down to the moment of “harvesting” the material. Every successful effort is a special moment of happiness that would not be there without the challenging stages beforehand. It connects my work to other art forms. Painters or fashion designers also experience stress if things don’t turn out the way they wanted. Every medium has its own problems.

Diana Scherer: ‘Harvest Recasted # 4,’ 2022, Paradys Arcadia Triennale, grown sculpture from soil, plant roots, 200 x80x120 cm // Photo courtesy of the artist

ARW: You talk a lot about the Anthropocene. What is the role of art in the relationship between humans and nature?

DS: Working with nature is a hype right now, strengthened by the coronavirus. I’ve been doing this for 10 years and only now do I feel like I am part of a movement. People are experimenting with natural materials and studying the religions of natives, such as Brazilian and Australian tribes, and they take care of their environment. I find it very beautiful and believe art has a key role to play by showing these images. Art helps us to ask questions and discuss the problems, but it won’t give us the answers. Finding the solutions is up to the scientists.

ARW: You emphasize root systems in your work. Why are you so captivated by them?

DS: Darwin already looked at roots with his root-brain hypothesis. He found that precisely the tip of the root has a brain-like function responsible for communication with other trees. But it is only recently that roots have been studied seriously. We are starting to understand that fungi, mycelium, plants, and roots form huge, complex networks through which they support and feed one another. Compare it to the internet; those networks are complex too, but it is still understandable compared to how roots communicate. Roots work together with fungi somehow, and the information can also be transmitted through the leaves and air.

Diana Scherer: ‘Interwoven #6,’ 2021, soil, plant roots // Photo by Diana Scherer

Diana Scherer: ‘Interwoven #6,’ 2021, soil, plant roots // Photo by Diana Scherer

ARW: You work closely with scientists and plant biologists from Delft University of Technology and Radboud University in Nijmegen. Do you see a future potential outside of art for the techniques you developed?

DS: They’re working on it. I worked with the TU Delft University of Technology to see how we can strengthen the material by genetic manipulation, which poses an interesting ethical question too. Three master students worked on it as their final project. One of them studied Future Earth Studies before, which is all about sustainability. I learned as much from her as she did from me. There are already requests from companies to start working with these materials, so I certainly see interest outside of the art scene.

ARW: Since your work consists of organic materials, perhaps they are not all archival, which is important in an art market. Do your works have a lifespan? Do they decay?

DS: You may think that my work always remains moist and alive, but unfortunately that is not the case. Roots love moisture and darkness, so as soon as you harvest them, they die and dehydrate. Mycelium is organic matter, therefore biodegradable, but it remains intact if you preserve it well. If you frame it and put it behind glass, it can be archived and sold. It is no different than an antique herbarium or a piece of paper.

Diana Scherer: ‘Harvest Recasted,’ 2022, Paradys Arcadia Triennale, grown dress sculpture from plant roots, seeds, soil, roots, 300x 150 cm // Photo courtesy of the artist

ARW: You created ‘Paradys Arcadia’ (2022) a grown sculpture dress in a natural environment. Can you elaborate on the creation process, especially how much control you had during the formation?

DS: The project finds its origin in the location, Oranjewoud (Orange woods), which was historically taken care of by three women, all part of the Dutch royal family. I was given the assignment to make something beautiful in honor of the artist-triad: Albertine Agnes, Marie-Louise and Henriette Amalie van Oranje. I wanted to go beyond showcasing the paradisiacal estate where the van Oranje family vacationed, so I designed three oversized (2.5 meter) dresses in line with each woman’s distinctive characteristics and her role in caretaking the woods.

For Agnes, the founder and nature lover, I chose a tree pattern to reflect her biophilia. I used microscopic images of beech trees—one of the species that Oranjewoud is renowned for. I grew two sheets for the front and back of the dress in a certain shape. I didn’t have to cut anything; I like the naturally ruffled edges. Finally, I shaped them around the mannequin with pins and minimal sewing. For Henriëtte, the ostentatious one, I used exaggerated patterns and grew a reptile motif on her back; I can’t let go of the biblical element of paradise. After Henriëtte’s nonchalance, Marie-Louise brought order into the woods again, so I reconstructed broken spider webs into a symmetrical pattern and added clean, natural lines to depict how she is still a meaningful figure for the local community.

Diana Scherer: ‘Harvest Recasted,’ 2022, Paradys Arcadia Triennale, grown dress sculpture from plant roots, seeds, soil, roots, 300x 150 cm // Photo courtesy of the artist

The process was abstract and technical, but also very creative. The templates of microscopic patterns I used to grow the dresses were under my control, but once underground, roots often do what they like. In this case it turned out even better. I always use a new pattern; it is a learning process, and my way of dealing with control. The world is full of patterns and people trying to find their own patterns. I’ve always looked for them in nature.