by Dagmara Genda // Sept. 1, 2022

Oil, that black viscous substance trapped in reservoirs below the earth’s surface, is burned in the blink of an eye but takes millions of years to form. 70% of the “black gold” powering the engines of today’s economies was formed 252 to 66 million years ago under very specific geological conditions. Though it was just discovered in 1859, we are now facing, at a consumption rate of 35.5 billion barrels a year, a depletion prognosis of 47 years, according to 2016 statistics from British Petroleum and the U.S. Energy Information Administration. Oil, as Monira Al Qadiri emphasised in our recent visit to her studio, is in everything around us: our shampoos, toothpastes, plastic bottles, computers, cars, packaging, the asphalt paving our streets, paraffin, just to name a few. This dire state has implications far beyond the energy and production concerns of the industrialised world. It is an addition largely responsible for an already unfolding environmental catastrophe.

The sheer prevalence of fossil fuels and their products has, expectedly, also had an effect on culture. In Al Qadiri’s case, the petrochemical industry remains the sole support of the economy in her homeland, Kuwait. It is the wealth derived from oil that has supported her artistic career and now forms the conceptual focus of her practice. The quickly growing art infrastructure of the Middle East is also a product of oil wealth. In recent years billion dollar investments have been made into museums, architecture and art shows, preferably with spectacular outcomes: the Louvre in Abu Dhabi and the National Museum of Qatar for example, both designed by Jean Nouvel or the Museum of Islamic Art designed by I.M. Pei. These investments help fund not only artists from the Middle East, but, in what is a complicated relationship, European and American artists as well.

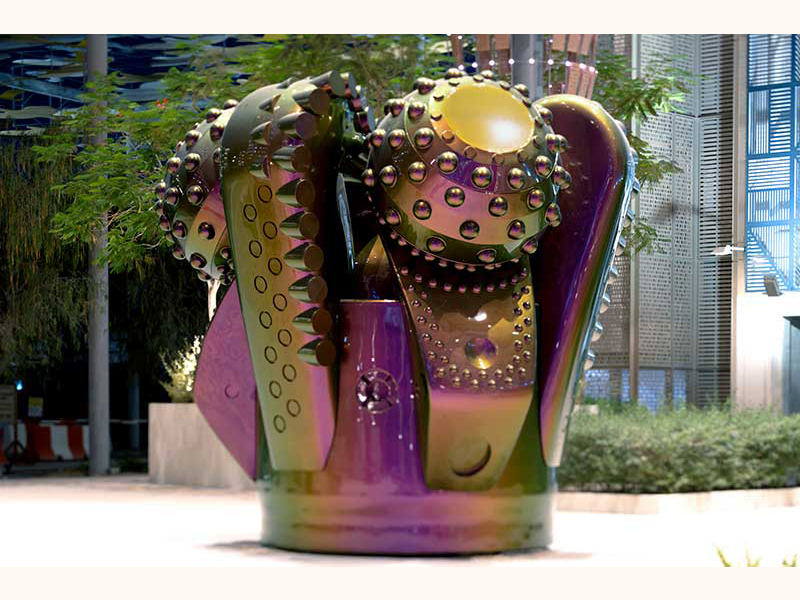

Monira Al Qadiri: ‘Chimera,’ 2021, Permanent Aluminium Sculpture, 450 x 470 x 490 cm // Photo courtesy of Expo 2020 Dubai

The now six-month old Russian invasion of Ukraine has laid bare the complex geopolitical dependencies for which oil is the life blood. Europe’s reliance on fossil fuels and its global effects was the topic of a Lena Johanna Reisner’s and Sonja Hornung’s ‘Fossil Experience,’ an exhibition programme in Berlin’s Wasserspeicher this past Spring. In light of the current rush to diversify energy sources and the reopened debate on nuclear power, its relevance has only increased since then. This is why, over September and October, we will be looking at the material and cultural effects of oil, from artists working in oil producing economies to those making work with, against or about oil. The articles over the next two months will explore the prolific but sometimes unacknowledged influence of fossil fuels.

Among upcoming articles will be an interview by contributing writer Juan José Santos with Brasilian artist and researcher Beto Schwafaty, who works with the cultural, environmental and political effects of the petrochemical industry. In his exhibition “Contract of Risk,” for example, the artist gathered everyday objects, political speeches, media and advertising to examine the effects of the “oil universe.”

Beto Shwafaty: ‘CONTRACT OF RISK,’ 2015, installation view of solo show at Luisa Strina Gallery, São Paulo // Photo by Edouard Fraipont, courtesy of the artist and Luisa Strina

Later in September we will be visiting the studio of Ana Alenso, who recently took part in the exhibition ‘Oil: Beauty and Horror in the Petrol Age’ at Kunstmuseum Wolfburg. The Venezuelan-born artist creates sculptures and installations made of materials sourced from mining and oil industries. The resulting poetic, but darkly dystopian objects, embody our dependence on non-renewable resources as well as portray a fascination with the aesthetics of the industry. The result are works that are both warnings and seductions; they mark the dangerous ambivalence of our society’s relationship to petrochemicals.

The questions arising from these practices and others that we will explore are formed not only by our role within the environmental catastrophe spurred by fossil fuels, but also our emotional and aesthetic relationship to it. What cultures and aesthetics has oil made possible? How deep does the influence of oil run? Can art about fossil fuels catalyse change or does it romanticise through its use of aesthetics? Oil, in our present day, is existential. It is not only in everything we use, but its effects also constitute our embodied experience of the world, both cultural and physical.