by Juan José Santos // Sept. 16, 2022

This article is part of our feature topic ’OIL.’

Half of the Brazilian flag is blacked out with oil, its green colour progressively devoured by black. Titled ‘From Abstract Orders to Material Progress’ (2010–2011), it is one of the many works that the artist Beto Shwafaty has dedicated to the problems stemming from oil extraction in his country. In his opinion, oil is one of the main “lubricants” of the political and historical narratives of the past century. He investigates the consequences and broken promises of its promoters, specifically through the lens of politics (such as the periods from the 50s until the 70s, characterised by diverse military and civil dictatorships) and economy (with Petrobras, one of the largest state oil companies in the world, at the forefront). In the 2015 show ‘Contract of Risk’ at Galeria Luisa Strina in São Paulo, he presented different ways of approaching a problem whose seeds were planted years ago. In his work ‘The Oil was Ours, or – It’s all Ideology, Stupid! (since 1950)’ (2013–14), the image of a billboard with the advertisement “The oil is ours,” links the present with the past. We speak with an artist who is not afraid to raise his voice against an omnipotent industry, which also has ties to the art world.

Beto Shwafaty: ‘From Abstract Orders to Material Progress,’ 2010-11, cinder blocks, fabric flag, oil paint, bitumen, copper, wood, stainless steel, cotton cord, 42x100x235cm, brass plate engraved in bass relief with automotive painting, 60x80cm // Photo by Eduardo Fraipont, courtesy of the Artist and Luisa Strina

Juan José Santos: ‘From Abstract Orders to Material Progress’ was your first attempt to address the effects of oil extraction in its connection to development in Brazil. What are the specific problems derived from that activity in your country?

Beto Shwafaty: The drive for progress normally comes with violence and destruction, and it is normally hidden from public view. The idea of modernism and of modernisation is, here, intrinsically connected to destruction and maintenance of old power structures. It just gives them a new “skin,” an update to seem more acceptable. Casual workers are now being considered “entrepreneurs” by government statistics and the so-called inclusion of identarian minorities is still on the level of tokenism. So, to make it short, the specific problems are the old problems: pervasive socioeconomic inequality, violence of many types, concentration of power and resources, monopolies and privileges being controlled and defended by the same old ruling classes (and families).

Beto Shwafaty: ‘The Oil was Ours, or – It’s all Ideology, Stupid! (since 1950),’ 2013-14, brass plate engraved in bass relief and black automotive paint, 60x100cm // Photo by Edouard Fraipont, courtesy of the Artist and Luisa Strina

JJS: Why have the problems related to oil production in Brazil concerned you throughout the course of your career as an artist?

BS: It occupied, and still occupies, quite a specific place as oil is probably one of the most invisible commodities present in our daily lives. It dictates the swings of the economy as it is used to generate energy and to produce goods. In the case of Brazil, the discovery of pre-salt oil fields in the deep sea during Lula’s government was being dreamed of as a way out from the colonial matrix to which Brazilian society is damned. The hope was that all the wealth from those fields would be invested into health, education and infrastructure policies, something like what happened in the Nordic countries. We now know that, as revealed during the Dilma Rousseff impeachment, the government was under the influence of international oil companies. This can be tracked back to, for example, Exxon and Shell’s support for politicians from the so-called Social Democratic Party (PSDB, namely senators Jose Serra and Aloysio Nunes). They supported the impeachment, but then proposed a change in the law that enabled the “participation” of international companies in the exploration of these new oil fields through supposedly public auctions. And this has been the case since the discovery of oil in Brazil, which inspired famous past campaigns like “The oil is ours!” So, the strong influence, interference and dependence of Brazil on the USA and international companies is always a heavy burden, one almost impossible to escape. Oil is, in one way or another, an invisible entity that allows me to touch on different focal points of the social and historical problems of Brazil.

Beto Shwafaty: ‘CONTRACT OF RISK’ 2015, installation view of solo show at Luisa Strina Gallery, São Paulo // Photo by Edouard Fraipont, courtesy of the Artist and Luisa Strina”

JJS: In your work ‘The Oil was Ours, or – It’s all Ideology, Stupid! (since 1950)’ (2013–2014) you link oil with military and civil dictatorships. I suppose that, through your work, one can see how this goes beyond a contemporary issue, but something rooted in time, even within European colonial histories.

BS: Yes, the problem is the colonial matrix and the persisting mentality linked to it. We cannot forget that all the valuable mining activities in the colonies helped to pave the way for a new and richer Europe. For example, Portugal paid its debts to the UK with gold and metals from Brazil and even today the UK is the biggest buyer of Brazilian gold. They buy around 80% and it is estimated that 30% of the total of the Brazilian gold today comes from illegal mining in the Amazon. The colonial and slave-holding matrixes were “modernised,” but they are still in place. The big English banks were born as insurers of slave ships and no reparations were made in this regard. I am increasingly interested in examining these relationships, in which colonial, historical and social issues are entangled, which also slip into identity and racial issues.

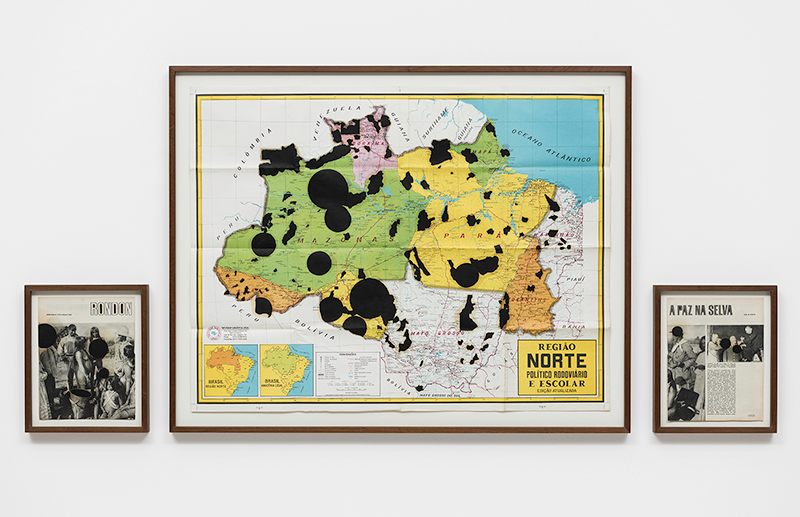

Beto Shwafaty: ‘PEACE IN THE JUNGLE,’ 2014, oil painting intervention on paper – map and pages from old magazines, 87,5 x 173 cm total // Photo by Edouard Fraipont, courtesy of the Artist and Luisa Strina

JJS: Artistically speaking, you worked with different ways of presenting your ideas. Is this a strategy designed to capture and expand the profile of viewers?

BS: It can be seen in this way, but mostly I try to use materials, languages, techniques that I believe will help in the communication of the issues I am materialising. It’s arbitrary and subjective sometimes, other times the choices come from aspects of the subjects I am researching. It can be from parts of a story, a footnote, a visual aspect of the visual identity of a firm, a prop made for a commemorative occasion, part of a building or architectural element, a newspaper cut, an artwork used by a third party to promote something and so on.

JJS: Do any of your works present possible ways of dealing with the problems you reflect on?

BS: Until now I believed my focus should be to raise awareness, start discussions, point to problems, because such problematic social, political, economic and historical issues cannot be solved by only one person. Also, art has zero power to change realities in scales beyond its small, closed contexts (and if it does that, it is a great victory!). But lately, after five years of a proto-fascist government in Brazil, which had strong support from the local elite (the same elite that somehow consumes and supports contemporary art) I am starting to rethink my work, how and what I could and would achieve if operating in other realms. It’s not clear yet but the desire is to expand to other areas, to think about function, agency, solidarity, alliances, utility, struggles … It’s a long conversation for another, and better time, I hope.

Beto Schwafaty: ‘CONTRACT OF RISK (THE WORKER, POLITICIAN, INTELLECTUAL AND REVOLUTIONARY),’ 2009–15, rusted iron, varnish, silicone rubber, aluminum, wood, 119.5x50x42.5cm // Photo by Edouard Fraipont, courtesy of the Artist and Luisa Strina