by Maryna Bakieva // Sept. 20, 2022

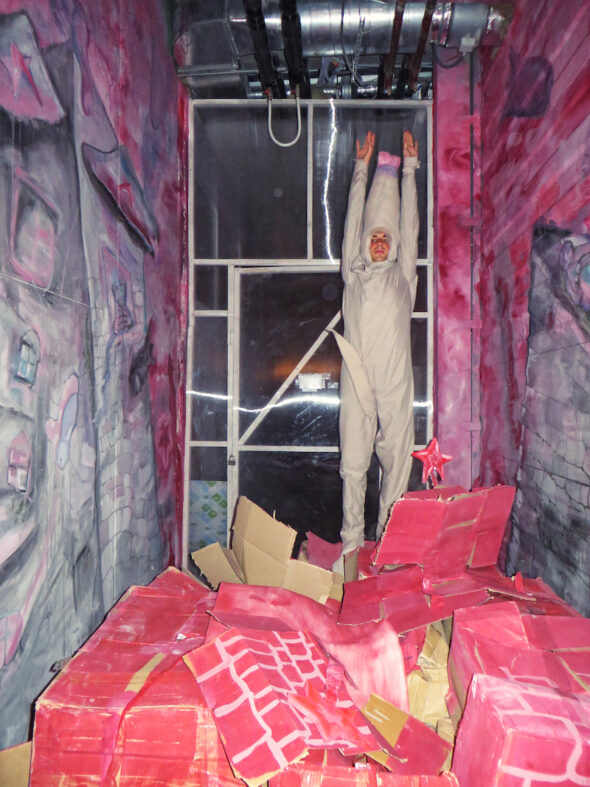

In 2014 Russia annexed Crimea and its forces began an invasion of the Donbas region. The same year, Ukrainian artist Valeo Kopysov found his own way to protest against Russian aggression. He put on a penis-shaped rocket suit and “landed” on Red Square. This absurd gesture was part of a performance at the Non Stop Media art festival in the just until recently occupied Ukrainian city of Kharkiv, which was curated by Sergey Bratkov, Ilya Isupov and Stas Voliazlovsky. Later, Kopysov reflects on the collective sentiment of his homeland: “Most Ukrainians would like to turn into a rocket now and fly high into the sky … Maybe then something could change? Everyone is already tired of what is happening. They want the war to end and peace to come as soon as possible.” The artist’s dreams of peace didn’t come true. Eight years later, Russia launched a full-scale war against Ukraine. Thus, the “Red Square” performance acquired additional meanings and visionary overtones.

Kopysov first acquired local fame because of VacciNation, a Kherson street art group that includes Kherson artists Sergey Serko and Marianna Tarish. Together they painted murals throughout Ukraine and abroad. In parallel, the artist developed his own solo career. In addition to performances, he works with video art and mixed media painting.

Maryna Bakieva: Your first performance, ‘Aggression to Nature’ took place in 2014 as part of a project in Kyiv Closed cluster #10. Why did you decide to do this kind of art?

Valeo Kopysov: I had a turning point in my work in 2011. Just then, I physically and mentally moved from the local graffiti environment to the universe of contemporary art. In 2014, I actively immersed myself in performance and happenings, though I did not lose sight of the theater of absurd and art-house cinema. Performance is, firstly, a communication with myself, with my essence, which I was only a little familiar with at that time.

Valeo Kopysov: ‘Red Square,’ 2014, performance // Photo by Densky Panchenko

MB: The year 2014 was filled with negative political events for Ukraine, but why did you choose to perform in the political context in the “Red Square” for the performance in Kharkiv?

VK: Until 2014, I stuck to a neutral political position. But Russian aggression made me realize that the history of Ukraine has been a persistent struggle for the state’s sovereignty and protection from the imperial snake. In this recurring cycle, there is not one generation that did not experience war. My escapism as an artist was fading away and I began to take the focus off the Ego and shift my attention to what was going on around me.

MB: Why does your performance include a penis-shaped rocket?

VK: The nature of the world is such that all weapons look like phalluses and the traces of destruction caused by these weapons resemble the outlines of a vulva. On the one hand, this is absurd, but on the other, it is simply physics. Phallic weapons embody the swagger of dictatorial greatness. I call such rulers DickTators.

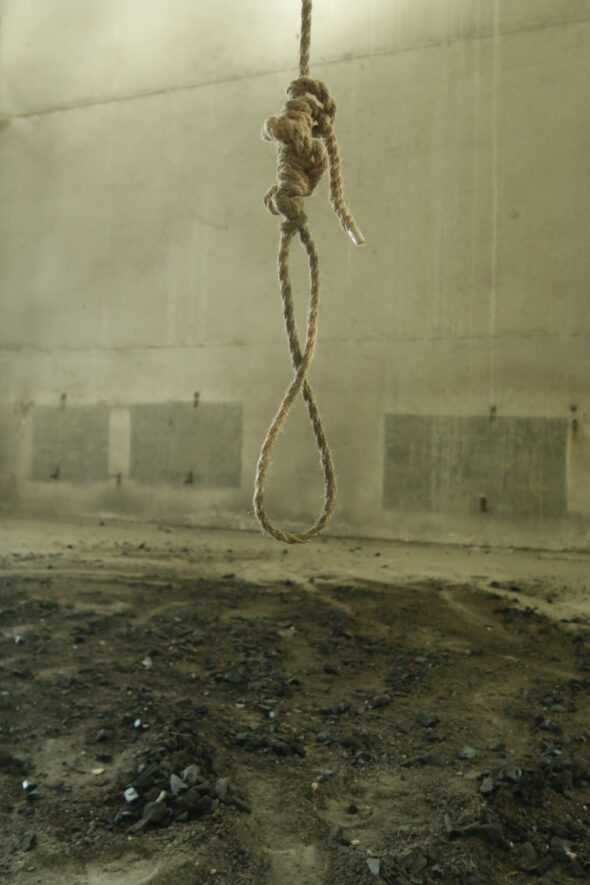

MB: In your early performances, there was some decor: you painted the wall or you made the buildings of Red Square. But the last performance, ‘Choke’ (2020), is quite minimalistic. There is only a naked you, a rope and ashes from a fire.

VK: Before the presentation of ‘Choke,’ I lived for half a month in a tent on the seashore on the island of Dzharylgach, a nature reserve in Kherson region. Most of the time, I was alone and thought about my way, where I aspire to be, and whether I am not betraying my principles. In ‘Choke’ I showed my ascetic ideas. I wanted to complete one of the life stages and I succeeded.

That was one of the most dangerous and traumatic performances: the whole body was covered in scrapes and abrasions, and there was a red mark from the rope on the throat. Some people in the audience wept or stood there in a stupor. The next day, at 5 am, I left again for 15 days with a tent and supplies. Wounds heal quickly in salt water. I swam with plankton at night, with dolphins during the day, walked with deer in the evening, burned fires, returned to primitive life without a phone, and thought and dreamed again.

Now Dzharylgach is occupied by the Russian army and, according to rumors, many animals on the island have now died of starvation. The invaders ate the rest.

Valeo Kopysov: ‘Choke,’ 2020, performance // Photo by Mantach and courtesy of the Artist

MB: You once said that the idea of ‘Choke’ was not accepted by the organizers of various art festivals or galleries for a long time. At the same time, you performed it in Kherson, the public of which (and I’m not talking about the art community but ordinary people), to put it mildly, is not disposed to provocative art. How did you persuade the organizers of GogolFest?

VK: That’s right, I sent the applications everywhere for several years with no result. Curator of the performance program at GogolFest, Eugenе Bal was also categorically against it, but he liked the concept. For three days, he did not give consent, asked to be softened and made not so dangerous, and the day before the performance, I told Eugenе, “either I do it or not.” I had nothing to lose at that moment. The curator admitted that his friend hanged himself, and this image triggered him. But finally, he agreed and supported me.

MB: If in 2014 you went to the Maidan to protest against the Russian invasion, now your protest tool against a full-scale war is art and Instagram, where you repost news about Russian war crimes. Many of those who participated in the protests in 2014 say that they have deja vu: they have already organized collections with help for the front line, volunteered, etc. Do you have a feeling of deja vu?

VK: Protest has become a way of life for a long time. One-half of the artists feel responsible for expressing in their works about today’s events, donating, and volunteering, for which they have enough time and energy, as it has affected them. The others work as before. They create art as if nothing has changed, and even the palette has not moved from its place. In the end everyone decides what they have in their hands—a Damascus steel sword or a toilet brush.

ValeoKopysov: ‘Choke,’ 2020, performance // Photo by Mantach and courtesy of the Artist