by Hans Carlsson // Nov. 30, 2022

I once attended a university course in Uppsala on the history of racism within a Swedish context. Over the course of several months, I learned about Sweden’s involvement in colonial enterprises through the establishment of colonies in the West Indies as well as through international trade. I also learned about the eugenic sciences of the late 19th and the early 20th century (for example the establishment of the State Institute for Racial Biology), forced sterilisation of citizens based on their “mental strength,” the hostile treatment of and discrimination against the Romani people during the heydays of social democracy, just to name a few. During our final seminar, suddenly, upon a discussion on the racial laws in 15th century Spain, where one of European history’s more violent forms of state racism occurred under the politics of limpieza de sangre, somebody brought up their “mixed” origins, claiming that in fact, his ancestors were Walloons, and that Walloon blood ran through his veins—an admission that made me wonder if he understood the content of course he was taking. The Walloons were a group of people in southern Belgium that emigrated in fairly large numbers to Sweden in the 17th century. Laying claim to Walloon blood has had, at least until very recently, positive connotations—a form of everyday eugenic assumption and claim to racial superiority over others.

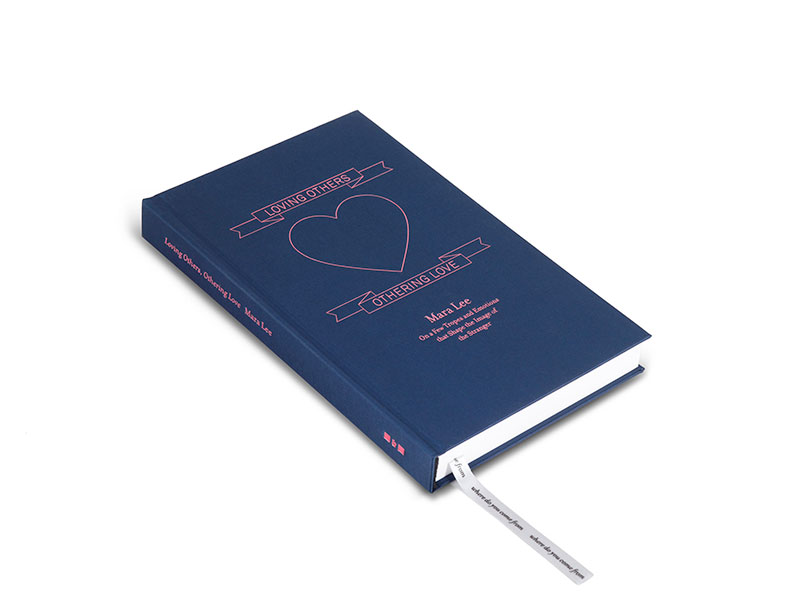

Mara Lee: ‘Loving Others: Othering Love,’ 2022, Praun & Guermouche

I came to think of this situation several times while reading Mara Lee’s new book ‘Loving Others: Othering Love’ (2022), which is described as a “multi-modal lyric essay that investigates the interdependence of love and racism.” Early on in the book Lee explains the term “Swedish exceptionalism,” first coined by the Swedish researcher Ylva Habel. “Swedish exceptionalism denies that racism in our country is structural. Racist expressions are reduced to aberrations committed by Nazis and right-wing extremists, not regular people.” A Swedish exceptionalist would have a hard time understanding that good intentions are not enough to prevent someone from being racist. I figure my Walloon colleague that day was acting out this same kind of cognitive distancing himself.

Mara Lee, born 1972, poet, author and professor in art theory and history at Konstfack University of Arts, Crafts and Design in Stockholm, sets out to scrutinise the assumption that good intentions, expressed through love and care, are enough to prevent one from being racist. Her field of analysis is language, and her reflections take literary sources as their point of departure. Everything from Mary Shelley’s ‘Frankenstein’ to Bharati Mukherjee’s ‘Jasmine’ are used as pedagogical examples to shed light on how racism takes form in, and is sometimes also simultaneously obscured by, language.

Mara Lee: ‘Loving Others: Othering Love,’ 2022, Praun & Guermouche

One of the book’s chapters is concerned with the tropes of travelling and moving. The idea of the movable subject is a modern dream about freedom and self-fulfilment, a dream that, in the history of film and literature, is often embodied in the white male hero who transcends different kinds of mental as well as physical barriers. Lee points out that such tropes exist in everything from ‘The Odyssey’ to ‘The Divine Comedy.’ However, the myth of mobility tends to hide other histories about moving and not moving. The history of not being allowed to sit or stand next to someone echoes from Frantz Fanon to Claudia Rankine and mirrors real societal events, for example Rosa Parks’ famous refusal to yield her bus seat to a white passenger in 1950s Montgomery, Alabama. Lee concludes: “What I am trying to demonstrate here is that a journey is not always a journey that can be understood in terms of binary oppositions or habitual associations” and that for some bodies the ”opposite of standing is not a seat, and the opposite of staying is not a journey.”

Lee’s literary analyses wouldn’t be so interesting if they weren’t placed in relation to texts of a more immediate tone and urgency. The poem ‘Public Transit: A Swedish Poem,’ is a great example. The poem is constructed of different lists: first a list of means of public transports in Sweden, then a list with specific times, then descriptions of real racist accusations and confrontations on the Swedish public transport system at these specific places and times. This poem effectively connects the literary tropes in the book with daily and horrifying scenes in Swedish public space.

One analysis that will stick with me is Lee’s discussion of Mary Gaitskill’s book ‘The Mare.’ The book is about a white family living in uptown New York: Ginger, a woman in her late forties, her husband Paul and Velvet, an 11-year old Dominican girl from Brooklyn who first stays with the family for two weeks as part of a summer camp program for low-income inner city families. The relationship between Velvet and her pseudo-adoptive parents turns into a many year bond. Velvet accepts them because they allow her to spend time with Ginger’s horse, a difficult, previously abused mare that everyone calls “Fugly Girl.” In contrast, Lee describes how Ginger chooses to take care of Velvet because of the young girl’s beauty. Ginger sees her as exceptional, and not like “the rest” of her racialised peers. Through the act of loving and aestheticizing the young girl, and imagining her to be less different to herself than at first expected, Ginger fools herself into erasing the power hierarchies that persist between a white adoptive mother and her black child.

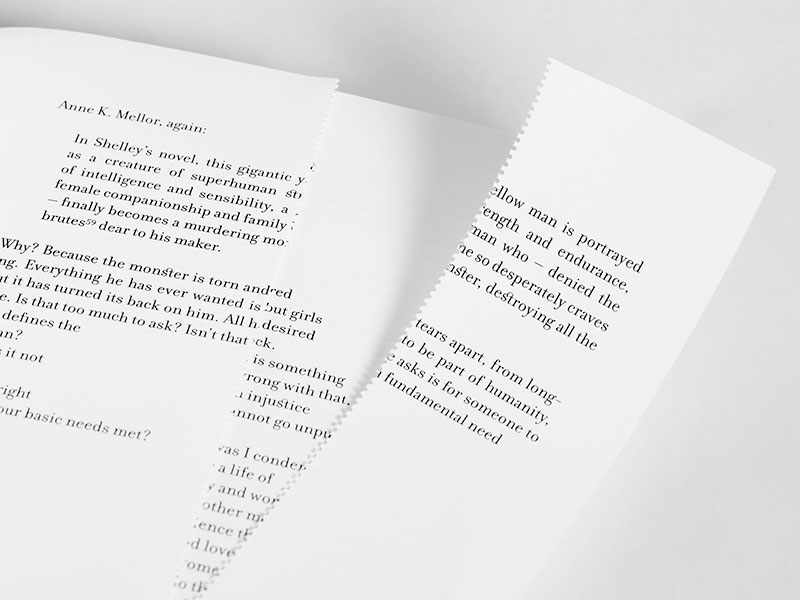

Mara Lee: ‘Loving Others: Othering Love,’ 2022, Praun & Guermouche

Lee’s careful attention to detail extends to the design of the book itself. ‘Loving others’ is a very precious object. Speaking to ideas of mobility, the book, with its patterned endpapers and the metallic embossed emblem on its cover, is meant to emulate a passport. Inside a ribbon bookmark is imprinted with the phrase, “where do you come from?” Sometimes the book also hints towards its own destruction. One page is perforated with small holes, suggesting that the page not only could, but should be ripped apart. The almost too precious design, together with carefully considered details align with Lee’s critical approach to beauty and love. It is as if the book invites you to judge it by its cover, promising to present a pleasant love story, when it does the very opposite. It gives you, the reader, the tools to critically dismantle love itself.