by Noushin Afzali // Dec. 16, 2022

Spanning an artistic journey over 30 years, Farkhondeh Shahroudi’s oeuvre encompasses installation, poetry, sculpture, and painting through which themes of displacement and trauma but also hope are addressed. Poetry, Shahroudi’s primary inspiration, manifests itself in drawings on paper as well as textile scrolls and books, which she then paints and embroiders with script. Both political and poetic, her works create a space where the line between word and image becomes blurry.

In September Shahroudi’s installation ‘Gülüzar’ (2022) kicked off the start of the two year programme of ‘Speaking to Ancestors,’ organised by Keumhwa Kim and Pauline Doutreluingne. Her site-specific work for Berlin’s Spittelmarkt dealt with the location’s history as a crossraods for travelers and merchants and later as the site for a “Siehenhaus,” a long-term care centre for the chronically ill. Currently her work can be seen at Kupferstichkabinett, organised as part of the Hannah Höch Förderpreis. It features books made of both paper and cloth that unite word and image, as well as a series of drawings dedicated to German painter Max Beckmann. Interested in the various currents informing her highly personal artistic vocabulary, we sat down with the artist to learn more about her process.

Fahrkondeh Shahroudi: ‘Beckmann war nicht hier,’ 2022, Kupferstichkabinett der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin // Courtesy of the Artist

Noushin Afzali: Tell us a bit about ‘Beckmann war nicht hier,’ your current exhibition at Kupferstichkabinett. How did your fascination with Beckmann begin?

Farkhnodeh Shahroudi: It first started when I was studying painting at the university in Tehran. I really liked his works, especially his self-portraits. When I received the Villa Romana Prize in 2017, I had the opportunity to live and work in Florence. There I was told that Beckmann had also lived in the villa and had worked in the same studio as I did. It was as if his presence spoke to me and I started communicating with him. In my works, it’s often the case that there is a doppelgänger with whom I communicate in the form of poems or letters, which I then either embroider or print or use as sound in my installations. On the wall of my studio back then I wrote, “Beckmann was here,” and from this sentence further works were developed. Later in 2018, when I was in Iran, I had a banner made by a craftsman resembling the religious banners used in rituals in Shia Islam inscribed with the words “max beckmann war nicht hier.” The story just goes on. I can’t really say how this fascination began. I only know there is always someone present in my works, either real or imaginary. The same process happens more or less every time I create something.

On a more personal level, both Beckmann and I left our home countries due to political reasons. Beckmann fled Germany in 1937 and sought refuge in the Netherlands. I left Iran in 1990 and found political asylum here.

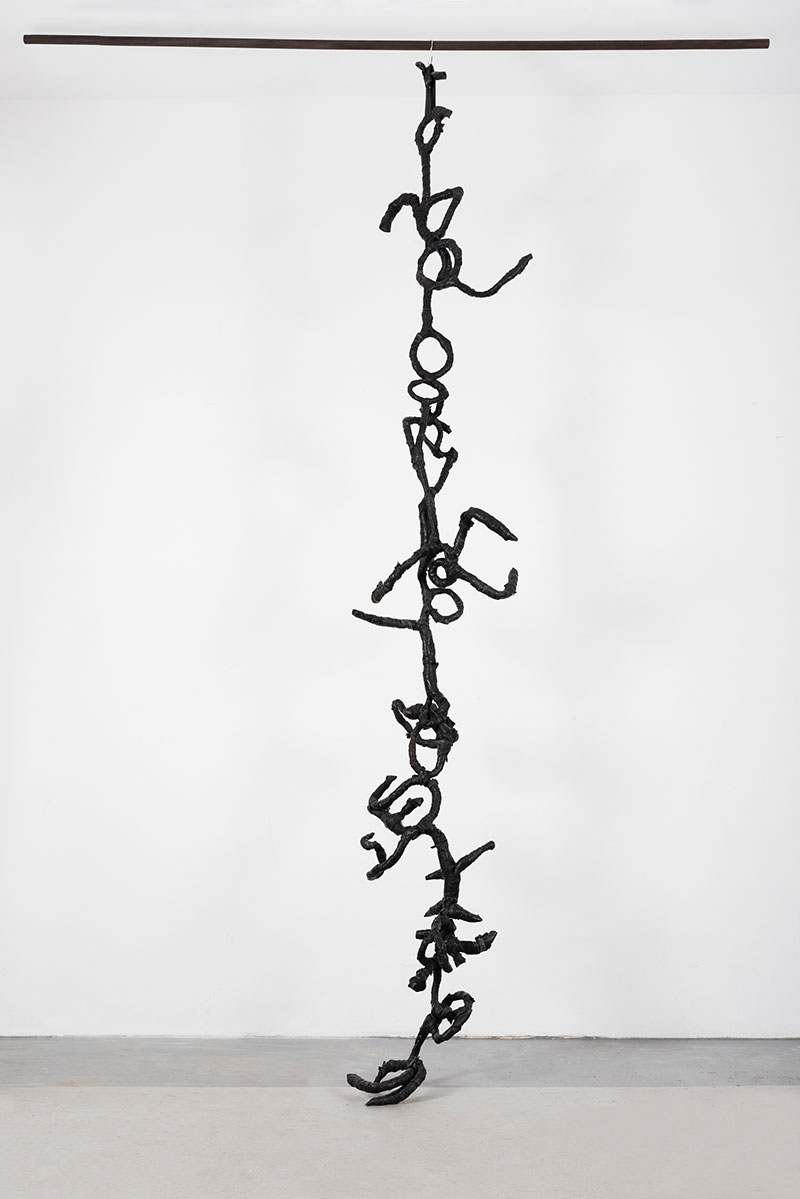

Fahrkondeh Shahroudi: ‘ICH HABE KNAST’ at Spittelmarkt, Berlin, 2022, ‘Speaking to Ancestors’ curated by Pauline Doutreluingne and Keum Hwa Kim // Courtesy of the Artist

NA: The paradise garden, a recurring motif in your works, reveals itself in the form of Persian carpets in your installations. Why did you choose this medium for representing this motif?

FS: The paradise garden with its most traditional form “chahar bagh” (four gardens) refers to a rectangular garden split into four quarters with a pond in the centre. This is a space of perfect geometry and harmony. During the reign of the Safavid dynasty in Persia (16th-18th century), the so-called “garden carpets” became the recurrent decorative models of the carpets. To me, the carpet with its ancient symbolism and enclosed form represents the space par excellence. In my installations, the carpets are transformed into “mobile gardens” that both free the imagination and embody the sense of not belonging.

My fascination with Persian carpets also goes back to when I first started as a painter. Carpets are not hierarchical, there is no up or down, you can turn them however you want and will still get the same form. I would do the same with my paintings and treat them as if they were carpets.

Fahrkondeh Shahroudi: ‘ICH HABE KNAST’ at Spittelmarkt, Berlin, 2022, ‘Speaking to Ancestors’ curated by Pauline Doutreluingne and Keum Hwa Kim // Photo by Piotr Pietrus

NA: Although your background is in painting, poetry and scripture dominate most of your works. How did this change take place?

FS: Text and language are the raw materials of my creation from which the image later takes shape. I seek to create, with language, a space of attraction for images. I have six siblings who are all artists as well. What connects our work is our love for poetry. I primarily still see myself as a painter. In my works–whether books, sculptures, or installations–I paint the space. I call these “three dimensional paintings.” I also use a lot of primary colours in my works which come from my background in painting.

There is also a thread that connects my works together. I always work simultaneously on different projects and have the feeling that you can find traces of different works in each other.

Fahrkondeh Shahroudi: Installation view from ‘Beckmann war nicht hier,’ 2022, Kupferstichkabinett der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin // Photo by Piotr Pietrus

NA: You write poetry both in Farsi and German. How do you go about this? Do you have a specific method of working with these two distinct languages?

FS: There is a difference [in language] in the types of books that I make. The fabric books are all drawn and written in Farsi, whereas the paper books consist of my writings in German. When I write in Farsi, I create different layers with words, therefore the texts are usually illegible.

Two works that are on view at the exhibition that demonstrate this method are ‘glossolalia’ and ‘Book in the Book.’ The former is a series of seven paper books, all written and drawn with the left hand, while the latter consists of drawings on fabrics with illegible texts in Farsi.

In contrast to Farsi, which is my mother tongue, I choose to write in German only with the left hand. In this way, I’m slower and can organise my thoughts better. My hand and thoughts follow the same pace. Throughout the years, I have developed my own German. It belongs only to me, I don’t care much about grammar or if my sentences are wrong; it’s Farkhondeh’s German. With this technique, I am more in touch with my thoughts and it also allows me to transcend borders imposed by language.

Exhibition Info

Kupferstichkabinett der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin

Farkhondeh Shahroudi: ‘Beckmann war nicht hier’

Exhibition: Feb. 11, 2022–Feb. 5, 2023

Admission: € 6 (reduced € 3)

www.smb.museum

Matthäikirchplatz, 10785 Berlin, click here for map