by Nina Mdivani // Mar. 7, 2023

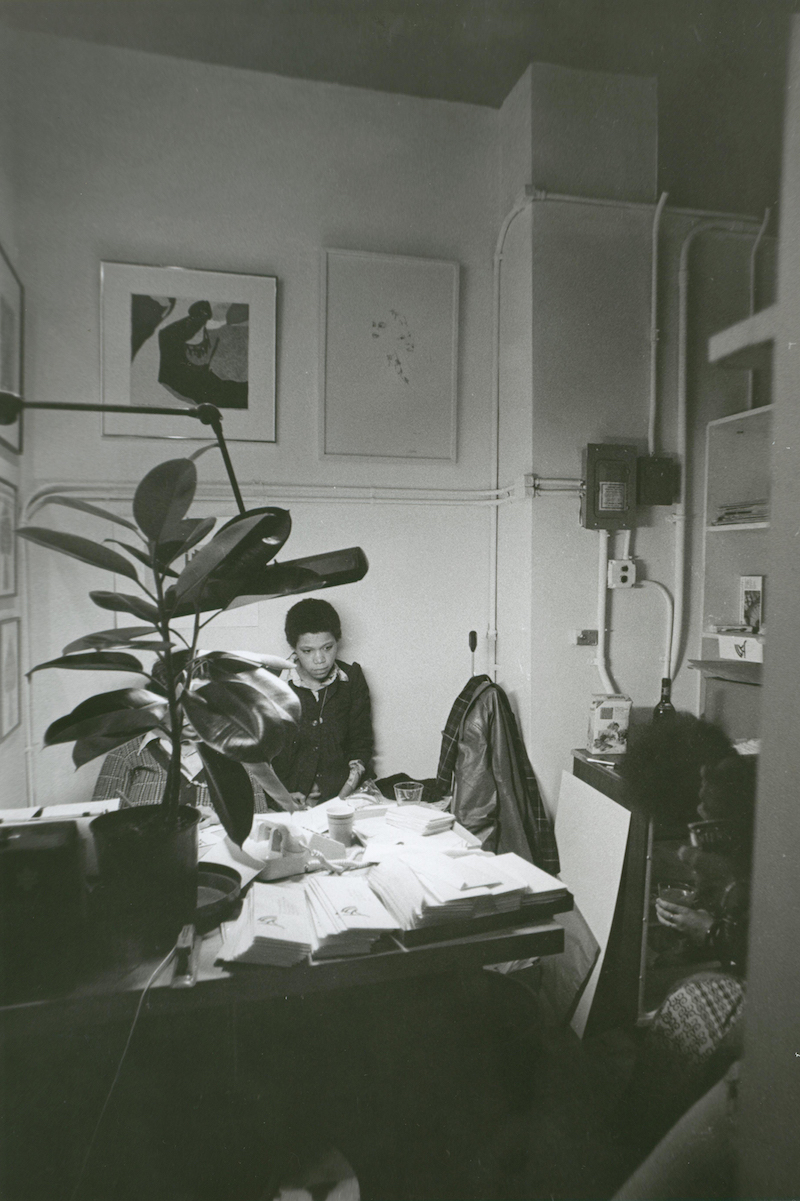

Just Above Midtown (JAM) was opened by 25-year-old visionary, artist, mother and educator Linda Goode Bryant in 1974. Located on 57th Street in New York, JAM was a self-defined, independent, Black-centered space. Over the following 12 years, the gallery moved three times, while offering a different model of operation within the dominant system of primarily market-driven galleries. Today, the notion of traditional galleries as gatekeepers and entry-points for artists is regularly questioned, but it’s important to remember that this open-ended, experimental ethos has its roots in forbearers like JAM. As a space welcoming Black artists, other artists of color, as well as white artists, JAM focused on access rather than exclusion, on creation and connection rather than sales and profit. Over the course of its 12-year run, JAM organized over 150 exhibitions, 130 performances, 50 film screenings and produced six publications, altogether collaborating with over 600 artists.

Linda Goode Bryant and Janet Olivia Henry (obscured) at Just Above Midtown, 57th Street, December 1974 // Photo by Camille Billops, courtesy the Hatch-Billops Collection, New York

The exhibition ‘Just Above Midtown: Changing Spaces’ at MoMA in New York took into account this formidable history and told the story of the space and its artists, using a wealth of archival materials. The exhibition, created with the active participation of JAM’s founder, was divided into the three different locations where the gallery existed: Midtown, Tribeca, and SoHo. The move to each new location was prompted by rent increases, struggles with landlords and the realities of New York gentrification. In a way, the story of this gallery is also the story of this city, changing and remaking itself every few years.

The curation of the exhibition underscores the communal nature of the space by presenting the full breadth of media the gallery artists engaged with. Sculptures made of pants hangers, artist hair, book covers, plexiglass and nylon mesh were hung next to carefully-framed woodblock prints and paintings. Video works were projected next to archival documentations of performances and miniature mixed-media installations. Curator Thomas Jean Lax approached JAM’s past as a careful anthropologist, centering the culture of free pathways that the gallery championed, while examining them through cross-cuts and sub-disciplines. The result was an immensely vivid display of talent that could serve as a model to replicate.

‘Just Above Midtown: Changing Spaces,’ installation view at The Museum of Modern Art, New York // Photo by Emile Askey

One of the first works encountered came from the printmaker Valerie Maynard (1937-2022). ‘The Artist Trying to Get It All Down’ (1970) exemplifies JAM’s ethos: an artist transcending external and internal limitations in order to fix her vision on paper, amidst the beautiful abstract mark-making and people surrounding her. Goode Bryant first met Maynard while coordinating the education department at the Studio Museum in Harlem, before opening the gallery. To her, Maynard’s workshop on printmaking and distribution exemplified the methods of engaging the wider community outside of a limited circle of collectors and aesthetes that Goode Bryant hoped to harness. Maynard was helping her fellow artists to find a wider reach, activating the marginalized Black presence.

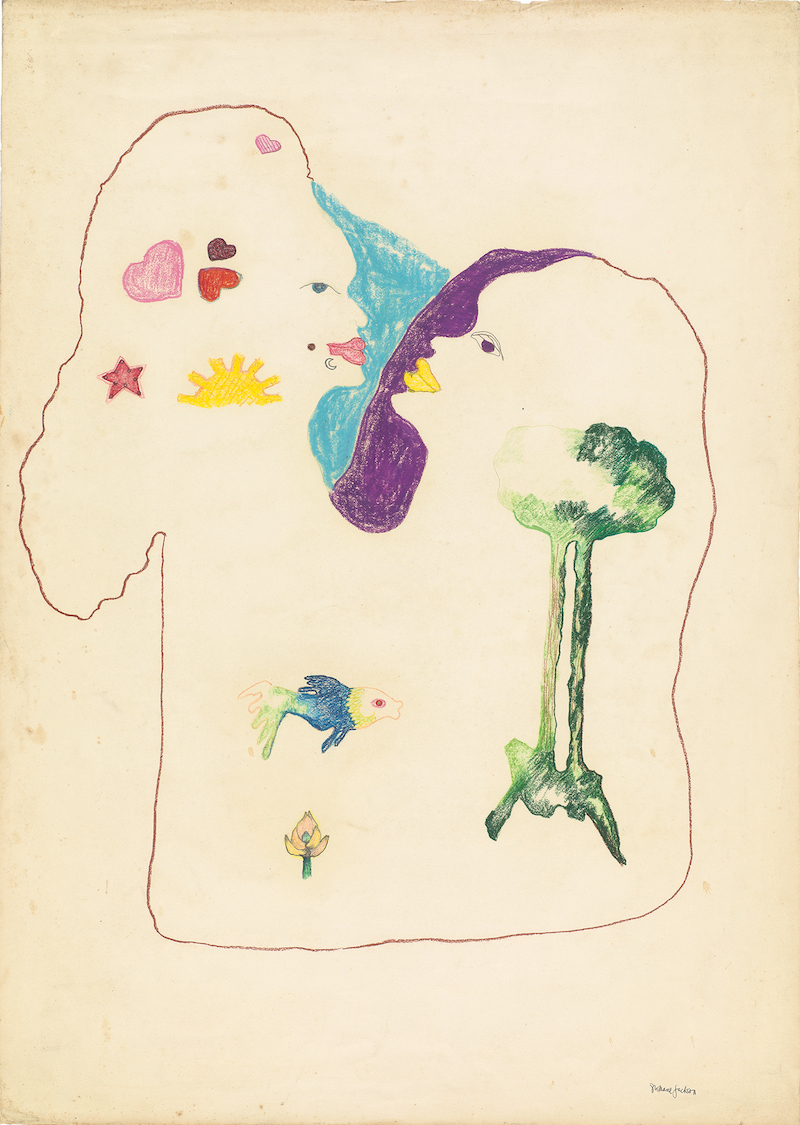

Suzanne Jackson: ‘Talk,’ 1976, colored pencil on paper, 104.8 x 74.9 cm // Courtesy the artist and Ortuzar Projects, New York, photo by Timothy Doyon

Suzanne Jackson’s work was also on view in this first room. Originally from LA, Jackson joined JAM for its inaugural exhibition, titled ‘Synthesis,’ wherein she presented ‘Maegame’ (1973). This show brought together the intersection of abstract and figurative artists. As Goode Bryant put it: “This was during a time where Black artists were debating whether or not you could be a Black artist if you were working abstractly or conceptually, that you can only be a Black artist if you were a figurative artist.” LA artists like Jackson rejected this division, producing several lyrical meditations on the nature of gender and rootedness, painting abstractly while reflecting real experience. Jackson was among many artists whom JAM sourced and invited from the other coast, a trend only then becoming the norm across New York art dealers.

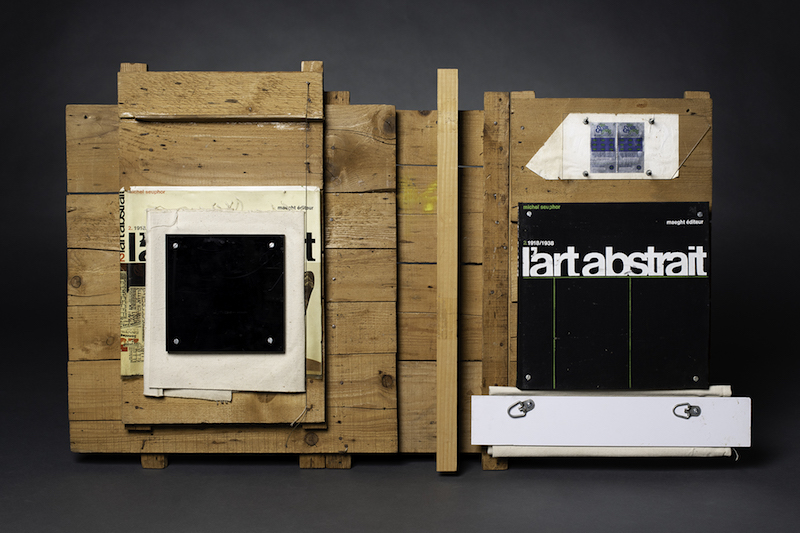

Randy Williams: ‘L’art abstrait,’ 1977, wood, canvas, book, book cover, plexiglass, wire, metal bolts, and lottery ticket, 61 × 104.1 × 12.7 cm // Courtesy the artist, photo by Mark Liflander

Senga Nengudi performing ‘Air Propo’ at JAM, 1981 // Courtesy Senga Nengudi

David Hammons, Howardena Pindell, Senga Nengudi, Lorna Simpson and Randy Williams were likely among the most groundbreaking Black artists working with the gallery, producing multiple collaborations and changing the notion of conceptual art for New York. JAM was embracing video and performance along with more traditional mediums of drawing, painting and sculpture. Found objects, together with leftovers of daily life, were materials that Hammons and Williams used to create their own system of communication. Randy Williams’ assemblages of Reagan postcards, magazine covers, wood, pistols, metal, acrylic paint, plexiglass, paper, condoms and books, among other things, created a system of coordinates not immediately accessible to the mainstream white culture of the 1980s, as not everyone was able or willing to access the references to pain, violence and exclusion.

Janet Olivia Henry was deeply engaged with the gallery mission, working at JAM in 1980s. Using found objects, she created painstaking small-scale installations featuring doll figures, inventing her own medium in the process. ‘The Studio Visit’ is simultaneously a social commentary about the power dynamics inherent in a white curator’s visit to a Black artist, and also a statement in support of this kind of model-making as a legitimate form of art practice. In the piece, a white curator is leisurely sitting in an attire reminiscent of a Baroque art patron and holding a frame, a metaphor the inequities of the art system. A Black woman artist is carefully listening to her visitor, the social hierarchy apparent in the nuances of the composition.

Janet Olivia Henry: ‘The Studio Visit,’ 1983, mixed media installation, 35.6 × 49.4 × 54.5 cm // Courtesy the artist

‘Just Above Midtown: Changing Spaces’ is as much about epistemology as it is about collaborative existence. Goode Bryant deeply believed in Black art and community existing at the center of its own universe and supporters, rather than on the fringes of the white-dominated art market narratives. The epistemology being built in this exhibition concerned the act of naming what was and what was not defined as Black art, based on what participating artists deemed appropriate, questionable or debatable. The exhibition presented a vital look at an alternative model of existing outside of white cubes of today.

Exhibition Info

MoMA

Group Show: ‘Just Above Midtown: Changing Spaces’

Exhibition: Oct. 9, 2022–Feb. 18, 2023

moma.org

11 W 53rd St, New York, NY 10019, United States, click here for map