by Annalisa Giacinti // May 9, 2023

On a sunny early spring day, the mountains surrounding Lugano are bright green and the lake that sits at the heart of the city takes on a deep blue shade. It is quite a scenic setting and a fitting visual prelude to ‘Unseen Colour.’ The photographic exhibition is currently showing at the LAC cultural centre of MASI Lugano, which is presenting newly discovered colour works by Swiss photographer Werner Bischof. Curated and directed by the photographer’s son Marco Bischof together with Ludovica Introini and Francesca Bernasconi, the show sheds an exclusive light on the work of one of the great masters of photojournalism of the 20th century.

Bischof’s work is extensive and thoroughly documented, looked after by Marco, who runs and manages his father’s archive, the Werner Bischof Estate. As much of it has been published over time and is already well-known to the public, the surprise was all the greater when, in 2016, Marco found boxes dating back to the 1940s containing hundreds of negatives on glass plates. At first, he seemed to have found three identical negatives for every image, only to later find out that they possessed different intensities and, once superimposed, they resulted in colour photographs of high resolution and visual perfection.

Werner Bischof: ‘Orchids Study,’ 1943, archival pigment, print digitally remastered // Photo courtesy of the artist and MASI Lugano

The exhibition occupies the entire first floor of the LAC’s building, and it uncovers around a hundred digital prints from 1939 to the 1950s, offering the chance to explore most of Bischof’s colour images for the first time. One of the early members of the Magnum agency, Bischof, like his contemporaries, was known to work predominantly in black-and-white, an obvious choice at a time when monochrome was considered more serious and sophisticated than colour, which lacked in credibility and was confined to the commercial domain. Yet Bischof, who had dreamt of becoming a painter and valued colour greatly, still employed it in his work. Now, almost 50 years after his tragic death—Bischof died prematurely in a car accident in the Andes at the age of 38—it is taking up a whole new life. Quite literally, Marco says, this discovery has had him “reorient the compass” of his father’s entire practice.

Werner Bischof: ‘Model with a Rose,’ 1939, archival pigment print digitally remastered // Photo courtesy of the artist and MASI Lugano

Three different cameras were found in Bischof’s archive—a Devin Tricolor, a Leica and a Rolleiflex—and the exhibition is structured around them. It covers the entire span of the artist’s career and constitutes a tour of the places he visited and lived in, while also providing historical evidence of photography’s technical evolution, and delving into what almost feels like a testament to Bischof’s professional versatility and experimentalism. The presentation begins with Bischof’s notes, sketches, letters, drawings, magazine features and reportages—a sweeping compound of the meticulous emotional and intellectual preparation that preceded the pictures.

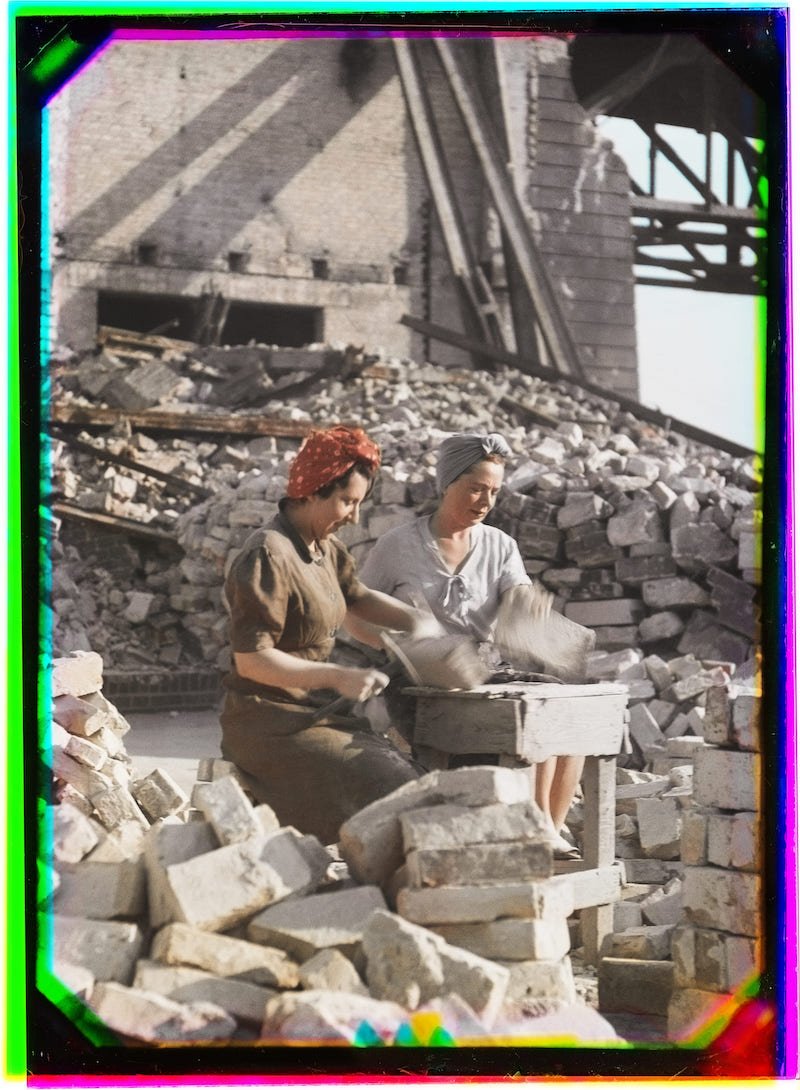

Werner Bischof: ‘Trümmerfrauen,’ 1946, archival pigment print digitally remastered // Photo courtesy of the artist and MASI Lugano

The first section is the one dedicated to works taken with the Devin Tri-Color, and consists of studio photographs from when Bischof worked for advertising and fashion agencies. The images featured here are of exceptionally high quality and definition, their colours so strikingly sharp and saturated that they evoke a Gaspar Noé-esque slant (minus the psychedelia), demonstrating a timelessness that makes even the most mundane objects, like an apple or a cat’s fur, engrossing to look at. All the photographs exhibited in this section are framed by fluorescent stripes caused by the superimposition of the three films and left consciously by the curators to make the process of development legible for the public.

The following photographs were commissioned by Swiss magazine ‘Du’ to document the aftermath of World War II in Europe, and look staggering: it’s rarely possible to look at pictures from that period in colour and to stand in front of them feels like witnessing an entire new history. There is an eerie yet alive quality to the photos depicting Berlin: “the bombed Reichstag looks like a monster,” says Marco, and it poignantly reminds of a past that’s neither too far away nor starkly different from recent events. More domestic and rural scenes of Italian countrymen, of Greek landscapes, animals and the countryside take turns with the dramatically lit portraits of Swiss steelworkers taken in 1943.

Werner Bischof: ‘The Reichstag,’ 1946, archival pigment print digitally remastered // Photo courtesy of the artist and MASI Lugano

Photos from Bischof’s many travels across North and South America, from the US to Mexico and Peru, which he took on 35 mm film with his Leica and are typically crisp and more accessible, come next. Additionally, the last section features works shot on the Rolleiflex and takes us East, to India and Japan, China, Hungary and Poland. These come in the characteristic square shape and much softer, velvety shades that render them filmic and dynamic.

Throughout our tour, Marco draws attention to how rich and varied his father’s output and practice were. Bischof was an all-encompassing photographer, “four in one,” reminisces his son. He engaged with studio and fashion photography, war reportage, journalism and travel photography with an unceasing curiosity that led him to travel and discover the world, for which his works seem to carry a sense of loving gratitude. Marco affectedly jokes about the fact that, to shoot on a Rolleiflex, one has to lower their head and almost bow in front of the subject. An image that speaks to Bischof’s devotion to photography as well as his family’s respect for his legacy, both of which are tangible in the space of MASI.

Exhibition Info

LAC Lugano

Werner Bischof: ‘Unseen Colour’

Exhibition: Feb. 12–July 16, 2023

masilugano.ch

Piazza Bernardino Luini 6, 6900 Lugano, click here for map