by Alison Hugill // Aug. 25, 2023

Yayoi Kusama is, today, firmly recognized as a kind of brand. Her artworks—think giant polka dot pumpkins and infinity rooms—are produced and exhibited the world over, garnering blockbuster institutional shows and visitor queues so long they rival Berghain. On the one hand, her most recent retrospective ‘Yayoi Kusama: 1945 to Now’ at Guggenheim Bilbao fits within this highly exportable, art star exhibition mould. On the other, if one pays close attention, it can provide crucial insights into how her brand came to be, and the extent to which she was actively involved in that process.

Yayoi Kusama, portrait // Photo by Yusuke Miyazaki

Earlier this year, luxury French fashion label Louis Vuitton paired with Kusama for a new line of clothing inspired by her work. An enormous sculpture of the artist was erected in the square outside Louis Vuitton’s Parisian headquarters, and life-like robot replicas inhabited the shop windows of several LV locations worldwide. These bizarre homages to the artist—who, at the age of 94, is rarely seen in public anymore—were criticized as a kind of hyperreal cult of personality gimmick. In one of the darker readings, a critic wrote: “Now dozens of Yayoi Kusama-bots are left trapped behind glass windows, endlessly locked into mindless production of her famous polka dots. Their eyes follow passersby as they paint random splotches on their glass prison walls.”

Yayoi Kusama: ‘Pumpkins,’ 1998–2000, mixed media, 6 pieces, dimensions variable // © YAYOI KUSAMA, collection of the artist

This interpretation feels all the more disturbing, and fitting, when one considers Kusama’s mental health struggles over the last five decades. The artist’s battle with anxiety and depression, as well as her suicide attempts, have been well-publicized and often reclaimed as fodder for interpretations of her repetitive artworks as a kind of healing or therapeutic practice. In fact, the curators and collectors behind the Kusama brand are always quick to point out that art has, since Kusama checked herself into a psychiatric facility in the late 1970s, served a life-saving purpose for her. The lack of direct contact with the artist in recent years, aside from her occasional meetings with art world bigwigs and curators, adds an aura of suspicion to these claims. Is she, in fact, a bit like these AI versions of herself, trapped and forced to produce polka dots ad nauseum?

The exhibition at Guggenheim Bilbao, which was first shown at M+ in Hong Kong and covers the last 80 years of Kusama’s practice, does shed some light on Kusama’s personal state as it relates to her commercial output. The curators of the show, Doryun Chong and Mika Yoshitake, will tell you that the Kusama brand we experience today is entirely consistent with her aspirations as a young woman in the 1960s New York avant-garde art scene. At that time, she was already producing fashion-adjacent wearables and attempting to blur the boundaries between high art and mass consumption, under her company “Kusama Enterprises Inc.”, which she founded in 1968 to market her wide variety of artistic work. For them, Kusama’s recent collaborations are not a sign of “selling out” or being commodified against her will, but rather make sense within the trajectory of her practice. In the end, she may have had more agency than many give her credit for in how this “final stage” of her work as a living artist came about.

‘Yayoi Kusama: 1945 to Now,’ installation view at the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao //©FMGB, Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, 2023, Photo by Erika Ede

The show has been neatly divided into six key themes that, for the curators, defined the artist’s life: Infinity, Accumulation, Radical Connectivity, Biocosmic, Death and Force of Life. The works are not categorized chronologically and different decades and styles are interspersed throughout. Kusama was born in 1929, and some of the works in the show are from as early as 1945, when she was only 16 years old. While the exhibition is neatly packaged (and its research is expanded in the accompanying catalogue), visitors who linger beyond the surface will also encounter a complicated picture of an artist who always struggled to make a name for herself in her home country and who was also not accepted as a serious artist abroad until fairly recently.

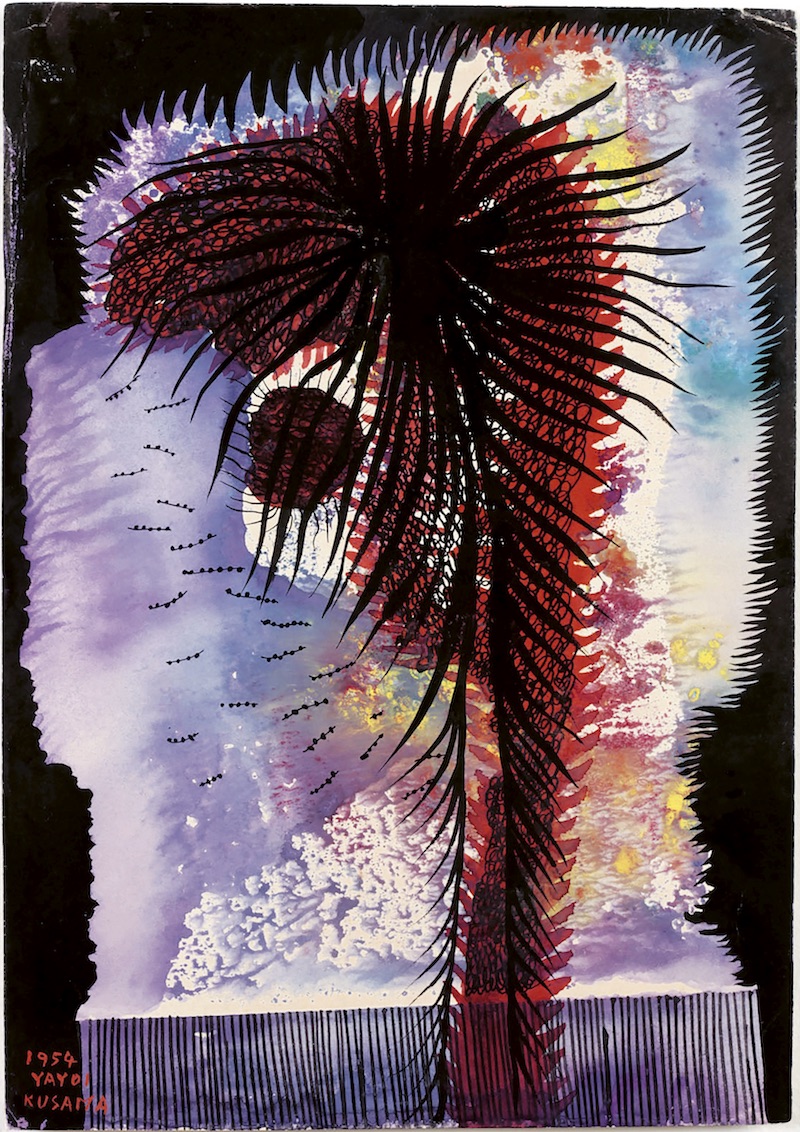

In light of this more complicated reading, it was the latter two thematics that held my attention the most. In the rooms displaying her work under the themes ‘Death’ and ‘Force of Life,’ we see one of the oldest works on display, a painting entitled ‘Atomic Bomb’ (1954), as well as some of her most recent works, made during the early days of the pandemic. ‘Atomic Bomb,’ as the name suggests, is a colourful and abstract rendition of the famous explosions that took place in Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945. Made less than 10 years later, it was still considered, in Japanese society, bold if not outright insensitive to engage with this tragedy in this way. An even earlier and more abstract work, ‘Accumulation of Corpses’ (1950), reveals a certain obsession with death and the trauma of this socio-political event in the artist’s oeuvre at the time.

Yayoi Kusama: ‘Atomic Bomb,’ 1954, gouache, ink and pastel on paper, 25 x 17.6 cm // © YAYOI KUSAMA, courtesy of Guggenheim Bilbao

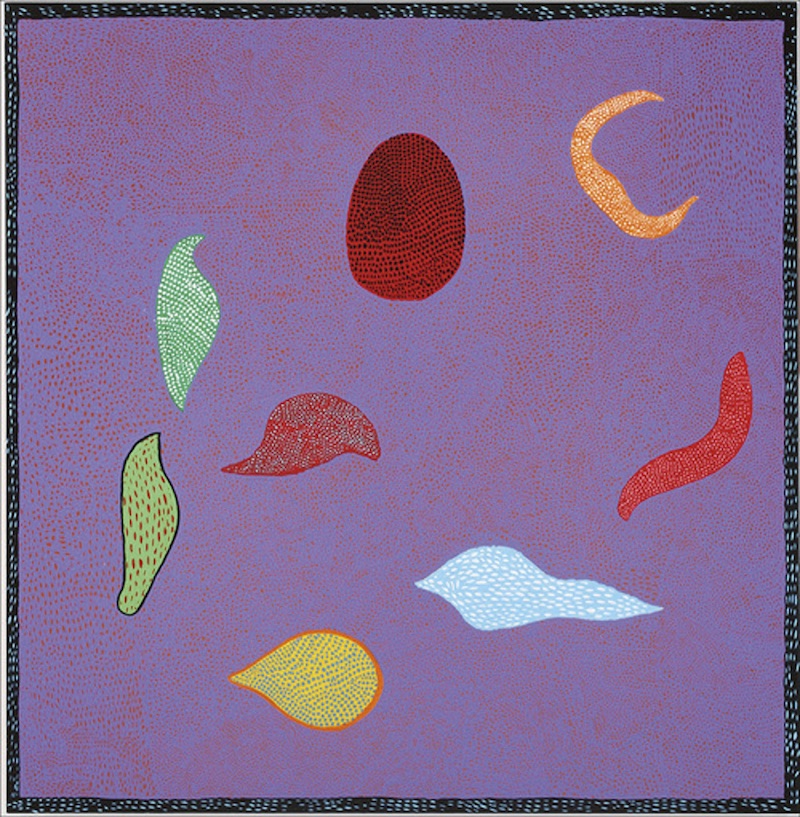

In the next room, under the theme ‘Force of Life,’ she is supposed to emerge triumphant, rejuvenated and transformed by her healing art practice. A series of large and colourful canvasses are covered with abstract, amoeba-like forms, suggesting a refocussing of her vision into the beauty of life in all its minutiae. Many visitors would also identify a certain naiveté in these more recent works, likening them to untutored, outsider art. But the morbid and slightly sinister elements are nonetheless still present in Kusama’s later work. And, despite the more colourful, upbeat and even politically-engaged nature of her artworks from the 1960s and 70s, there appears to be a thread of disillusionment and deep unhappiness that can’t help but emerge throughout the years and the themes addressed. How does this square with the bright and happy-go-lucky brand that Kusama’s artworks represent internationally today?

Yayoi Kusama: ‘Souls That Flew in the Sky,’ 2016, acrylic on canvas, 194 × 194 cm // © YAYOI KUSAMA, Collection of the artist, Courtesy of Ota Fine Arts, Victoria Miro, and David Zwirner

In June of this year, just before this exhibition’s opening in Bilbao, Kusama came into the limelight again. Hyperallergic contributor and media studies researcher Dexter Thomas, in his review of the show’s catalogue, dug deeper and exposed what he refers to as the “clear pattern of banal racism” in Kusama’s work, which interested parties like curator Yoshitake have attempted to consistently deny or re-frame in their pursuits of Kusama as a “champion of racial equity.” Citing several examples of anti-Black racism in her autobiography and elsewhere, Thomas suggests that the book (and the show itself) form part of a strategy to sanitize Kusama for western audiences, in an attempt to further improve her marketability. Thomas also notes that the lack of rigorous engagement around Kusama’s racism might be a by-product of her well-publicized mental health struggles, which gave her a level of immunity from criticism.

Coming out of the retrospective, with its well-packaged thematics and highly institutionalized narratives, a more critical observer might be left with more questions than answers. Behind the bright and repetitive commodities on display lies a deeply complicated individual, the particular characteristics of whom are routinely exploited or discarded, depending on how they serve the brand. Perhaps this could be said of other artists, for whom the cult of personality has become deeply entwined with the works themselves. But ultimately Kusama’s body of work, when presented in such a sweeping way, speaks for itself, and might even reveal a lot more than its curators want it to.

Exhibition Info

Guggenheim Bilbao

‘Yayoi Kusama: 1945 to Now’

Exhibition: June 27–Oct. 8, 2023

Admission: € 16 (reduced € 8)

guggenheim-bilbao.eus

Abandoibarra Etorb., 2, 48009 Bilbo, Bizkaia, Spain, click here for map