by Dagmara Genda, studio photos by Laura Schaeffer // Sept. 5, 2023

This article is part of our collaboration with Berlin Art Week.

The defining feature of Via Lewandowsky’s practice is not a material or a theme but an attitude—a nearly palpable, restless curiosity. It is also what makes his work so difficult to pin down. His output includes sculpture, sound, public art and performance, among other things. “A fascination with the stuff of daily life is what drives my work,” he explains, as he shows me various objects in his studio: an elongated woodblock flute, a 3D-print, a swathe of framed hair that frantically repeats “Fuck!”, a piece of glass. “I see something and think, ‘that doesn’t work the way it should’ and then I have to fix it.” Above the artist’s head hangs an analogue clock, the hands of which do not move but its face spins at a dizzying rate.

Lewandowsky studied stage design in Dresden in the 1980s, but his thesis presentation was a particularly visceral four-person performance that later led to a loosely defined collective called “Autoperforationsartisten.” Though their blood and guts aesthetic lends itself to comparisons with Hermann Nitsch, the context of the group—whose original members consisted of, in addition to Lewandowsky, Micha Brendel, Else Gabriel and Rainer Görß—was not in the least esoteric or dogmatic. If anything, the as-yet-unregulated realm of performance allowed the artists to break free of the strictly defined dictates of the GDR communist regime. Framed through the lens of Lewandowsky’s current practice, one might consider his early performance work as marked by the same curiosity that now guides his approach to materials. Just back then, the material was the body itself.

If the penchant for self-harm in the performances of the Autoperforationsartisten can be tied to Lewandowsky’s notion of “fixing” everyday objects, it becomes quickly clear that the artist’s “repairs” propose a world rotating on a slightly different axis. Objects and bodies remain recognizable, but they are off-kilter and the usual relationships between them have been reconfigured, if not destroyed. When it comes to the strictly regulated and surveilled bodies of the former communist regime, one might conclude that the irrational spectacles and self-harm of Lewandowsky’s collective helped keep the individual grounded in an undeniable, physical reality. Their work enacted an escape, if not a viable alternative, to the time’s penetrant, paranoid dogma. Released from this dogma with the fall of communism, the collective dissolved in 1991.

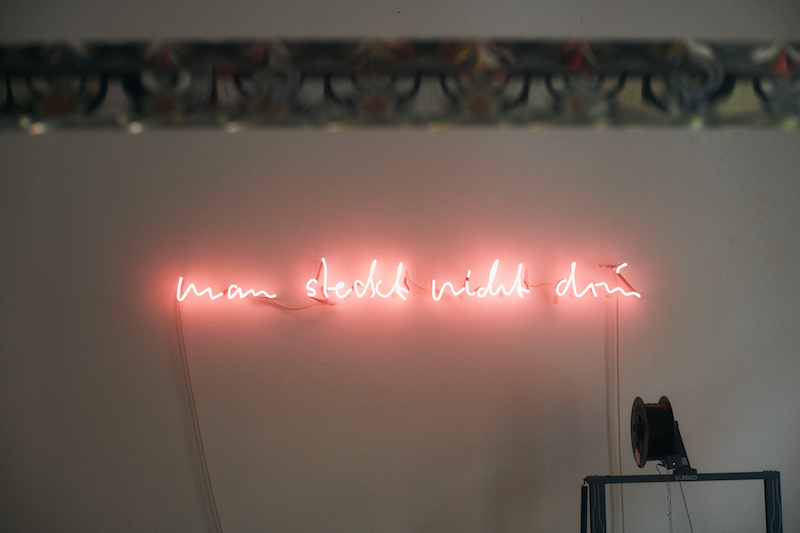

Today, artists are more or less free to express themselves as they please and so, in Lewandowsky’s studio, the question “what if…?” blooms into a myriad of possibilities. Scanning the room I see evidence of the artist’s prolific production. Numerous 3D prints of cartoonish scribbles adorn one wall (“I don’t know if these constitute a ‘work’ yet,” he says), large black and white screen prints hang on another, piles of square paintings balance atop a table (“These are constantly being made in the background, so to speak”), squiggles of neon are found on the floor and walls. I hear an Imam’s call to prayer after the artist switches on a small, ominously ticking cuckoo clock (“This piece has become more controversial over time”). As our conversation continues, I get the sense that this visibly exuberant creative freedom comes at a certain price.

The sheer potential of material culture weighs upon the objects that Lewandowsky realises. Indeed, it weighs upon the artist himself. “Life is too short to stick to one thing,” he repeats throughout the studio visit. The pressure of brevity takes on a sense of urgency in his work. It is most directly illustrated in his racing clock, but applies to his oeuvre as a whole. Taken together, his varied practice becomes a proposition. It alludes to the roads not taken, to all the permutations that have not yet been actualised. In this respect the cursing swathe of hair starts to read like a panicked realisation that one is running out of time. While history did not end in 1991, as Fukuyama would have it, perhaps something else did.

On the floor next to a window, whose sill is covered by small 3D prints, stands a long wooden crate filled with styrofoam packing peanuts, in which the word “bedeutungslos” [meaningless], scribbled in neon, is softly nestled. The piece began with the acquisition of the crate, which often is, more so than the gallery or museum, the final home for a work of art. Most art collections remain in storage and many collectors accumulate primarily as a status symbol or investment. “What is the meaning of the piece to such a collector,” asks Lewandowsky, “and what is the meaning of the work of art at all in this case?”

As a stand-alone question, the work simply reiterates a common complaint about the art industry, but when seen in light of the artist’s practice as a whole, ‘Version of concern (meaningless)’ (2021) is a work struggling under the weight of potential. If anything is possible, then which path should one choose and is choice ever anything other than arbitrary? The flip side of creative freedom, or perhaps creative freedom in a (relatively) free market economy, is a persistent feeling of doubt. It’s thus no surprise that the artist has spent a good deal of time creating mechanised suicide-machines in the late 1990s and early noughts. One such apparatus includes a motorcycle helmet that hangs from an ominous three-legged metal contraption. The individual is intended to strap their head in and spin until their neck snaps. Another device consists of a glass cube into which one inserts one’s head. One can then pull on a chord that will set a water pump into motion, thus filling the box with liquid and drowning the willing victim. These propositions, however, are not actual death machines, but sculptures. They are not evidence of an existential crisis, as much as a crisis in art. They could be seen in light of a tradition that is not necessarily dying out, but asphyxiating itself with its own tools.

Doubt is also addressed in Lewandowsky’s work through a direct reference to religion, which has arguably never been completely disentangled from art. In the work ‘Good God’ (2019), a public art installation between the two towers of Bamberg Cathedral, the word “Good” is spelt in neon but the second “o” flickers as if at the end of its lifespan. In a recent piece from 2022, the words “wie bitte” [pardon?], cut out of metal, are installed behind the altar of the St. Mathäus-Kirche in Berlin. Combined with an 80-speaker sound installation of ambient noise derived from prayers and hymns, the phrase puts the question of audience at the forefront. To whom are we speaking and are we even being heard?

The task of art, it is often said, is to ask questions, though these questions often become a branded line of inquiry that acts as an artist’s calling card. Even if the answer to the questions posed remains unknown, the position or authority of the artist should remain secure. In Lewandowsky’s case, I conclude after the visit, questioning serves to destabilize more than the everyday world he attempts to “fix.” His varied oeuvre explores and questions art’s ability to create meaning, as well as tacit assumptions about authorship (which is, of course, related to authority). The fetish of a signature is discarded in favour of recombinant flows; the artist becomes less an author and more of a site. He is the node around which the material world is reordered.

Artist Info

Exhibition Info

Stiftung Kunstforum Berliner Volksbank

Group Show: ‘Schlaglicht’

Exhibition: Sept. 13–Dec. 10, 2023

kunstforum.berlin

Kaiserdamm 105, 14057 Berlin, click here for map