by Adela Lovric // Oct. 13, 2023

This article is part of our feature topic Privacy.

Examining data, the causes and effects of its collection and classification, Mimi Ọnụọha reveals what is absent and why these blank spots matter. Her work on missing data sets exposes what she calls “algorithmic violence”—the exclusionary tendencies within technology—and creates sites for the opposite to surface and replace it.

Ọnụọha’s artworks, including two that are currently on view at Berlin’s Gropius Bau, interfere with the dominant logic and core digital infrastructure to inscribe expulsed stories, meanings and values. The short film ‘These Networks in Our Skin’ (2021) and the site-specific installation ‘The Cloth in the Cable’ (2022) both revolve around cables as an element of networked society that disturbs the perception of the digital as something immaterial, somewhere up in the cloud. Together with the film inspired by Igbo cosmology, the installation of cables meandering through the space, wrapped with earth-toned fibres and embedded with an assortment of fragrant spices, centers the obscured and the excluded while creating a sense of embodiment and warmth where least expected.

The Brooklyn-based artist and researcher spoke to us about these and other artworks, as well as her practice at large, which aims at a deeper understanding of the realities and histories omitted to benefit some and disadvantage others.

Mimi Ọnụọha: ‘These Networks In Our Skin,’ 2021, video still, single-channel-video in HD // Courtesy of the artist

Adela Lovric: How did you get into exploring issues surrounding data collection?

Mimi Ọnụọha: The way that I got here was a bit accidental. I was already doing work that involved thinking a lot about technology and culture. I did this small project over a decade ago, an intervention. I was getting catcalled a lot in the city, close to where I live. I decided to create a server that would be attached to a phone number so that whenever somebody would catcall me, I could walk up to them and give them a piece of paper with the phone number. They thought it was mine, but it was connected to what I had coded online. If they tried to call it, nothing would happen. They couldn’t leave a message or I wouldn’t pick up. But if they texted, I had programmed these strings of text responses that would go to them and I would be able to see this conversation that would go back and forth. This was before chatbots, and now it’s pretty typical, but at the time it just wasn’t really as prevalent.

What was interesting about it was that at first it created this strange sense; I wanted the distance of tech but I also felt the intimacy of us being still in this conversation. I did this for a summer and, by the end of the summer, I realized that I had gathered this byproduct: a data set of my cat-callers’ phone numbers. And it was one that they had opted into because they had texted me. At the time, people kept asking me what I was going to do with that data set. But I was just so interested in this idea of what that data set could hold and what it couldn’t. Having their phone numbers didn’t at all speak to the experience of doing the project and all of the weird fear and strangeness of it. But, on the other hand, the data set was the actual artefact—the thing that could be easily pointed to. That was really what got me into thinking about data. I was making myself the subject and object of data collection and seeing how much was packed into the process, but also how much it couldn’t contain.

Mimi Ọnụọha: ‘*69,’ 2014, performance, data collection intervention // Courtesy of the artist

AL: What have you been primarily aiming to reveal about the world through your artistic explorations of algorithmic lives?

MO: There are two sides of my practice. There’s one that is about trying to make sense of this world that we have inherited, to think about what is involved in this act of creating data and the value in it, and asking what does that trace back to. I think a lot about absence, about missing things or what you can’t quite see, know or hold. I like missing things because I think that they become a way to think about a system. And, in fact, it’s so hard to think about systems. I use the missing to make sense of the opacity of socio-technical systems and the ways that we are really wrapped up in them. I don’t ever really know what I’m trying to reveal until I’m there doing the work, but I know that there’s a logic to this technocratic system that we’re in. And I want to make sense of that logic, because that has to do with the second part of my practice, which is about how we actually want to live and what it looks like to have a different form of relationality with each other.

AL: So you, in fact, also suggest a different world?

MO: Yes, I think so. I like to drop the hints or the beginnings because a different world can’t be created entirely by me. But certainly I like to play with those ideas. I think there’s a kind of dialectic between the two—what is actually happening now and what could be happening? What do we want? What do we need to uncover? What do we need to bring? What do we need to reposition?

Mimi Ọnụọha: ‘The Library of Missing Datasets,’ 2016, mixed-media installation // Courtesy of the artist

AL: What kind of data are you looking into as part of your artistic process?

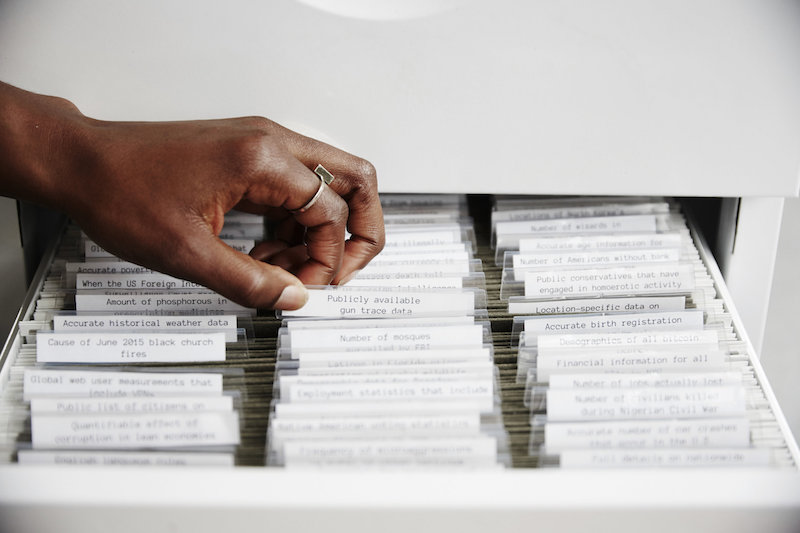

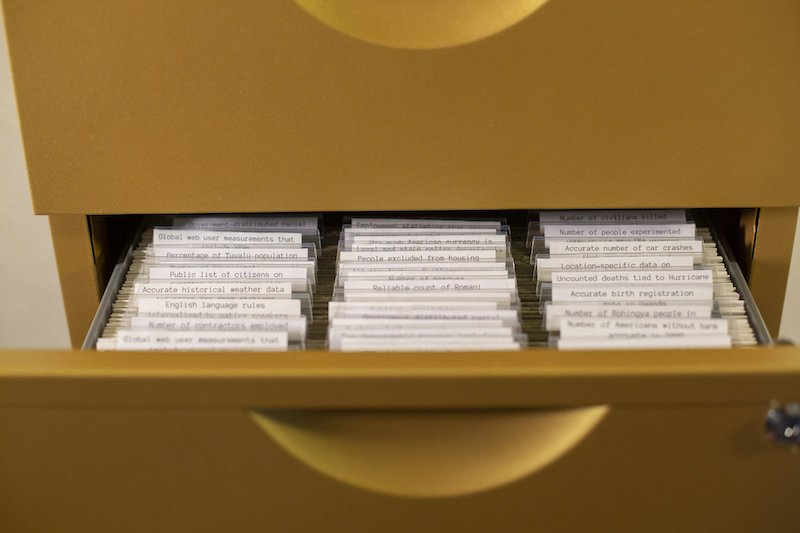

MO: That question always depends on the project. I can give two examples. The older project I have is ‘The Library of Missing Datasets.’ In that one, I’m just interested in any data that is not collected in a space where so much is. I started with the number of Black civilians killed by law enforcement, because at the time, that was a missing data set, even though there was so much data collected about crime, justice, policing and so on. The fact that this one thing wasn’t collected said everything about the underlying logic and value of where that data emerged from. The ‘Missing Datasets’ project is not just about collecting missing data, but also about why these things are missing, what can be quantified, what the terms of datafication are, who has the agency and power, and so on.

For the project I’m working on now, I’m trying to create a machine learning model that can predict places in the US that have mass graves from a particular moment in US history. To do that, I have to create a lot of different types of data sets that can be thrown into the model. Part of the reason I’m making the model in the first place is that I see how machine learning is a tool of precision that people believe and it becomes a form of evidence in a way that the historical stories and some of the oral narratives around these graves do not. I think of this as a kind of impossible model in a way, in that it’s going to predict very mathematically the likelihood that different counties have these graves, but will not be able to dig for them. And, to flush it out, we’ll have to go back to the sources that don’t carry much weight in our society, anyway. That’s a different process of data collection; a bit more historical, and a lot more about talking with people and working with primary and secondary sources. The very process of trying to get that data is so challenging that I don’t know exactly how the project will unfold. But, in every case, for me, data collection is very contextual and tied to what the aims of a project are. In fact, I think this is how it should be.

Mimi Ọnụọha: ‘The Library of Missing Datasets 2.0,’ 2018, mixed media Installation // Courtesy of the artist

AL: Can you expand on ‘The Library of Missing Datasets’ and the different examples of data you looked into?

MO: This work started from the observation I mentioned before, which was that I would see there are spaces where lots of data were being collected. And then there would be this curious omission, a blank spot where nothing was collected. The first one I saw was civilians killed by the police in the US, Black people especially. As I dove deeper into it, I started to see that there were patterns of missingness that were not all the same, but certainly consistent in the groupings that they fell into. Some things were missing because they were difficult to quantify; there was something elusive about them. For example, no one really knows the amount of US dollars in cash outside of US borders, because cash has this quality that’s different from credit card or digital transactions. It creates this blank spot, which a lot of underground economies know and take advantage of. Sometimes there would be data sets where the group with the means to collect it did not have the incentive to. There’s law enforcement and the number of people killed by law enforcement. The police could very easily collect that, but they have no incentive to, so why would they? There were some examples where there’s a burden of collection, where people don’t want to collect it because they’re not convinced that collecting it will give them more of a benefit than the difficulty in having to do it. For instance, there were a lot of data sets originally around sexual assault where they were very approximate. There was some missingness to them because a lot of people, women especially, would not speak about some of these things because of how they were punished when they did.

Mimi Ọnụọha: ‘The Library of Missing Datasets 2.0,’ 2018, mixed media Installation // Courtesy of the artist

AL: What does it look like to exhibit something that is missing?

MO: The project became a way to not just visualize an absence, but to materialize it, and to think about why things are missing and why it’s important for things to be put into data. The piece became a holding place for this idea that not everything can be rendered in data. So that’s the conceptual idea behind the piece. There are three different versions of the actual presentation of the piece, and they’re all filing cabinets with folders that contain the titles of these missing data sets. The folders are empty and, in many cases, people can look through the folders, lift them up, and it’s really great to see them interact with it. They can see that it’s empty, they get that it’s missing. I try to change the missing data sets depending on where it’s shown. A lot of my work is about context. Right now, the piece is being shown in New York and a lot of the missing data has to do with New York and the US.

‘Ether’s Bloom: A Programme on Artificial Intelligence,’ Mimi Ọnụọha, installation view, Gropius Bau 2023 // Photo by Luca Girardini

AL: Your two works currently shown at Gropius Bau also focus on the obscured elements of our digital reality; you interfere with them to hack their inscribed values. Do you see this interference as a kind of radical representational gesture that locates change in places people rarely think of but are foundational—radical in the sense of going to the root of the matter—or is there something else behind these two works?

MO: It’s “yes, and.” I think that is certainly part of it. I keep talking about how I like to make work about systems and how there are logics that can be difficult to pick up on because they’re not materialized. Often you can feel the logic of a system when you hit up against it. In that work, there’s so many different pieces being put together. There’s an ease of coming into it and experiencing the piece, but there’s quite a lot I’m thinking of and pulling from in terms of Igbo cosmology and technical concepts. As you say, cables are not what people consider when they think about the digital and even the internet. And yet these are at the heart of digital and that infrastructure. There is a sort of viscerality to them.

When I think about cables encircling the globe, I think of a circulatory system and in fact, they are. Scientists are using internet cables to be able to learn more about the world itself, for tasks like predicting earthquakes. There’s this strange interplay between our technological infrastructure and the Earth itself. To intervene at that point feels a bit like intervening at the source. When I keep thinking of the logics and values in a system and how do you think about where do they lie, they’re at the core of the structure. I think these cables are that core.

There is no going back to a time before tech, nor is there a time after. In the piece, we’re bringing in these different artefacts to play with that logic and to suggest what it would look like to put different types of logics into this. The thing I love about art is that there’s a conceptual, theoretical part of it, but then there is this extremely material, sensorial element. And I think that installation is really working on both levels. There’s something that feels quite abstract and removed, but then there’s a warming of it. You see in the colors, the smells, the feeling of the space, it is doing something else with computation. Something I very much love about art making is advancing an argument that is one that you feel in your body, rather than just one that you are meant to dwell on and read about. And I think that’s part of the intervention as well.

Artist Info

Exhibition Info

Gropius Bau

Group Show: ‘Ether’s Bloom: A Programme on Artificial Intelligence’

Exhibition: Aug. 10, 2023-Jan. 14, 2024

Free entry

gropiusbau.de

Niederkirchnerstraße 7, 10963 Berlin, click here for map

Ford Foundation Gallery

Group Show: ‘What Models Make Worlds: Critical Imaginaries of AI’

Exhibition: Sept. 7-Dec. 9, 2023

fordfoundation.org

320 E 43rd St, New York, NY 10017, click here for map