by Adela Lovric // Jan. 5, 2024

This article is part of our feature topic Utopia.

Housed in a three-story, former department store in Berlin, Lawrence Lek’s exhibition ‘NOX’ presents a near-future speculative world, in which self-driving cars—a “band of eternal wanderers, always on the move”—play the lead part. In a smart city populated by sentient machines, fictional AI conglomerate Farsight Corporation handles four different classes of these vehicles, each of whom serves a role that corresponds to their predetermined personality traits, modeled after one of Hippocrates’ four temperaments.

Through computer-animated videos screened on the first two floors, visitors follow the film noir-like journey of Enigma-76—a melancholic, existentialist car specialized in delivery—who gets assigned a five-day rehabilitation program at the center NOX (short for ‘Nonhuman Excellence’) to fix their defiant behavior. The rehab, aided by equine therapy with a horse that leads them to their Jungian shadow self, teaches them about their memory, ancestry and how to evolve. Additional narration activates over the locative headphones at different points throughout the exhibition space, giving context from the poetic voice logs of Enigma-76 and Guanyin, their AI therapy bot named after the Buddhist goddess of compassion. On the top floor, a video game offers the visitors a chance to engage in an interactive training simulation and treat various undesired car behaviours, further tapping into a futuristic version of corporate wellness culture that frames productivity as excellence.

What is seen on-screen or heard over the headphones partly reflects Lek’s installations at the physical venue—including cars, car parts and a panopticon-like construction surrounding the space—as well as the space itself and the location of the show. Lek does a similar thing of making the liminal space between real and fictitious porous by weaving some of the existing concerns surrounding AI, such as increased automation and surveillance, into the fabric of his imagined universe.

Remixing elements from his previous works in his characteristic way of “worldbuilding for nonhumans,” Lek imagines a future in which AI strives for agency and freedom, underlined by utopian considerations. In our interview, the multimedia artist discusses different aspects of ‘NOX’—his largest exhibition to date, presented by LAS Art Foundation and curated by Carly Whitefield—as well as his idea of “incremental utopia” running through the show at Kranzler Eck and across his artistic practice.

Lawrence Lek: ‘NOX,’ 2023 // Copyright Lawrence Lek, commissioned by LAS Art Foundation, photo by Andrea Rossetti

Adela Lovric: What was the starting point for this exhibition at Kranzler Eck?

Lawrence Lek: There’s the long-term journey of the work, and also, the opportunity to do something large-scale and site-specific in Berlin. In 2016, I made a video essay called ‘Sinofuturism’ that looks at futurism from the perspective of the Chinese history of technology and society. I was thinking about how AI is portrayed essentially as a non-human force that can either save or damage humanity. The way that Chinese industrialization is portrayed in the media is actually a mirror image of how AI is portrayed. Again, this was in 2016, so AI and the Chinese industrialized workforce are both presented as this inhuman, hive-mind mass that is capable of doing huge amounts of learning, labor and work. This idea made me think that instead of empathizing or positioning things from the point of view of mainstream media—with questions like what does AI mean for humanity and where is it leading us—it was more interesting for me to ask what might the world look like from the perspective of these people of the future, this future Other. From the narrative point of view, that was part of the reason for this AI subjectivity. The protagonist is a self-driving car, whose dilemma is that they can drive anywhere but they also can’t. They have freedom but also limits bound to that. In terms of inspiration, it’s very much about how these explorations around AI and society and my previous work relate in 2023, because the context now is quite different from seven years ago.

Lawrence Lek: ‘NOX,’ 2023 // Copyright Lawrence Lek, commissioned by LAS Art Foundation, photo by Andrea Rossetti

AL: The car is a repeating character across your practice. Why did you choose a self-driving car as a protagonist here in ‘NOX’?

LL: In much of my earlier work, I was thinking about how the first-person point of view in video games is meant to give the player the feeling that they’re controlling the character, they control the camera, they have a position and a certain kind of agency in the world. With ‘NOX’ I was developing that video game aesthetic further. On the top floor, we have a touchscreen-based game and, in the videos, it’s more a cinematic point of view. For both, I’m using a game engine to do things, but what is cinematic and what is game-like is slightly diverged, because of that first-person point of view, which is meant to give the illusion that you are a person going through the world in the game. On a narrative level, there’s the idea of a journey through space; sometimes it’s a person walking, here it’s a car on a journey, in my 2017 film ‘Geomancer’ it’s a satellite. Sometimes a character is literally a vehicle, and sometimes they are just in motion. For me, that’s also tied together with this first-person point of view.

Lawrence Lek: ‘Geomancer,’ 2017, video still // Courtesy of the artist

AL: Right now everyone is concerned that AI is taking our work and that our hard-earned knowledge, skills and positions are becoming obsolete. Your project, however, imagines a future in which humans seem to be entirely out of the picture. Is it a post-human environment?

LL: It’s ambiguous where people are. I don’t actually characterize it as a post-human environment. With one of the scenarios of full automation, you might think, are people not necessary or are they just at home, ordering stuff and playing video games? One scenario is that the people are gone because they are being served. In the show, there are also different ideas about how people might want to be served, whether it’s delivery, security or fun. In my previous work, as well, there is this idea that hospitality and care are a big part of automation. But here, the scenario is a little bit more ambiguous.

Lawrence Lek: ‘NOX,’ 2023 // Copyright Lawrence Lek, commissioned by LAS Art Foundation, photo by Andrea Rossetti

AL: In this environment in ‘NOX,’ there is the same kind of suffering from the pressure of excellence and progress that affects humans. It seems to transcend humans and continue to possess AI. You’ve dealt with similar issues of labor previously in your work. How do you view it in this context?

LL: Very simply, the cars have a job. And when they can’t do their job, they get retrained. Previously, I was thinking about labor, but here, in a weird way, I’m thinking about unemployment. In the video, when the car is in the car junkyard, the car is thinking—this is my future. It’s kind of a memento mori. There’s a very strong labor relation in the piece in terms of what’s visible—the cars—and what’s invisible. Where have the people gone? Where are all the masters? There is also the very tangible thing, like this particular car, the main focus of the show, who can’t do their job because their memory is full. The fact that they are in this environment is because they can’t do their job. So labor and those questions are definitely there, but viewed from another angle.

Lawrence Lek: ‘NOX,’ 2023 // Copyright Lawrence Lek, commissioned by LAS Art Foundation, photo by Andrea Rossetti

AL: To ask back the question you posed in your exhibition opening speech: How do we live together in the upside-down world? The world that you’ve built in ‘NOX’ seems to suggest a dystopian atmosphere. Is there a place for hope and utopian ideas?

LL: I wouldn’t say the mood of the work is utopian or dystopian, because that’s a judgment of the society in the film. I’m not trying either of these things. The question is essentially: What do you do with the knowledge that your world, or their world, is upside down? How can you fit in with that?

In the videos, there is one car who feels that they can’t fit in so they go and crash on some road. Another car doesn’t want to fit in, but makes a moral compromise; they have to work for the police because, ironically, that’s the closest thing to an ideal job that they can find.

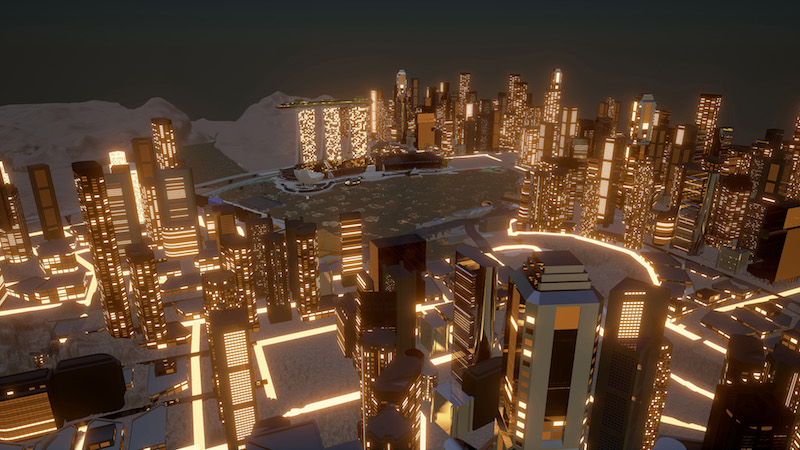

Considering the classical notion of utopia as a place, there’s this idea that we’re set in the smart city. But it’s not this shiny, new smart city. It’s half-built, a bit crap, dusty, not much going on. It’s not like an ad for a smart city at all. It’s not a tier-one smart city, it’s a tier-three smart city that has grown because it’s on an important infrastructural route. So in terms of the utopian question—is utopia an environment or is it a way of living together—I was thinking of this idea of utopia not as a top-down grand plan, but as a gradual improvement over time.

For example, in the world of ‘NOX,’ the first-generation cars are driving fine until one day they crash and that’s it. The second-generation are driving fine one day, the next day they’re saying “I don’t feel so good” and the third day they crash. And here we have a 10th-generation one where the company realizes that three months into their 24/7 job, they start to have some problems, so that’s when they need to take a break or have a retreat. The utopia here is incremental rather than top-down and all at once. For example, the way that software or product development works is iterative and incremental as opposed to all at once. I suppose it’s not a utopian scenario, but it’s better than the scenario a year ago. Maybe the fact that these self-driving cars are at least collectively aware of having a community is a good start. It’s not the best by far but the awareness of their own position and possible future agency is the best start to what that could later be.

Lawrence Lek: ‘Skyline,’ 2014, video still // Courtesy of the artist

AL: How would you say this idea of incremental utopia has evolved in relation to your previous work, like the ‘Bonus Levels’ series (2013-16) that dealt with a more site-specific urban context, or the ‘Sinofuturism’ trilogy?

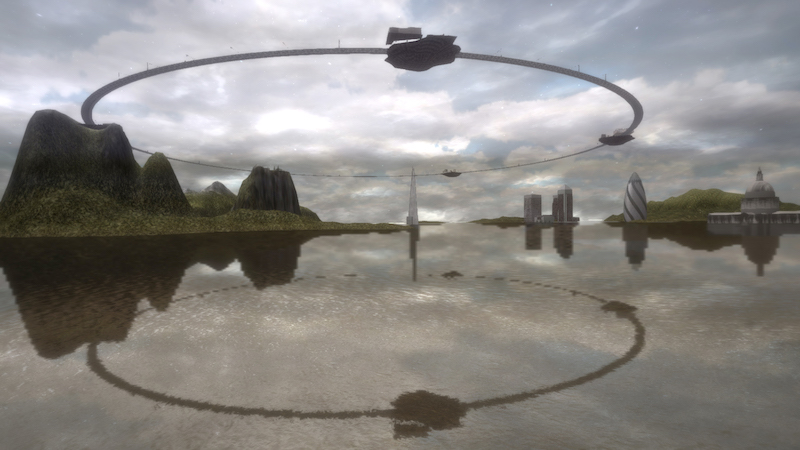

LL: One common thread linking all my work is the idea of the first-person wanderer, or explorer who confronts a changing world. In terms of overall world-building, and in the literal scenography and set design of the films and games, there are “classical” elements of utopian symbolism: cityscapes, social structures, conflicts between the individual and collective and so on. But since the ‘Bonus Levels’ series, which basically created alternate histories or counterfactual future versions of already existing sites, I thought that the simplest form of utopia is not structural, but experiential instead.

In 2013, I wrote an essay called ‘Pyramid Schemes’ in which I thought of skyscrapers—that ubiquitous building form that encapsulates both modernist utopia and hypercapitalist dystopia—as a kind of vertical time machine. It was from some reflections about London’s Shard, the tallest building in the city that had recently been completed, which also reminded me of the phenomenon of high-rise viewing platforms in skyscrapers around the world, like the Petronas Towers in Kuala Lumpur, or the Empire State Building, for example. As you move up the elevator to the viewing platform, you emerge from the congested cityscape at street level and gradually rise to see the city from above. This privileged viewpoint of a literally higher position was, of course, something that used to be strategically useful, as with fortifications and castles, but I thought that the skyscraper could also give access to this utopian point of view.

I wanted to create a similar experience through gaming and film. So, in the game ‘Sky Line’ (2014) you could journey around an elevated train line that travels between five stations, each containing artist-run and independent galleries and project spaces across London, looking down at the rest of the drowned cityscape below. In the end scene of ‘Geomancer’ (2017), the AI satellite flies to the top of the Marina Bay Sands towers in Singapore and sees the world anew. Similarly, in ‘NOX,’ which is a kind of deconstructed video game in the form of an exhibition, you as the visitor experience the fictional world of the film on the first two floors, and when you arrive on the top floor, you look down at the different zones that you inhabited just a few minutes ago. There, on the top floor, you also play the game ‘NOX,’ in which your identity shifts from being an explorer of the world to a Farsight employee, being inducted as a trainee AI psychologist. So, what I’m saying, again, is that in my work, maybe utopia is a personal experience, a kind of journey or awakening, rather than a physical space.

Artist Info

Exhibition Info

LAS Art Foundation

Lawrence Lek: ‘NOX’

Exhibition: Oct. 27, 2023–Jan. 14, 2024

las-art.foundation

Kranzler Eck, Joachimsthaler Straße 7, 10623 Berlin, click here for map