by Lorna McDowell // Feb. 16, 2024

This article is part of our feature topic Utopia.

At the height of catastrophic and man-made late-capitalism, what can the organic world, and plants in particular, teach us about potential utopias? Merging her experience in ethnobotany—the study of human-plant interrelations—with artistic practice, Chilean artist, educator and activist Patricia Domínguez explores the dimensions of spiritual and non-human intelligences. Her works, often presented as shrine-like assemblages, are both ancestral and futuristic. They become rituals, exorcisms and a form of meditative prayer, unveiling a poetic vision of contemporary life that is deeply connected to the Earth, and opposing our present colonial and extractive relationship with it.

In 2023, Domínguez’s video work ‘Holographic Milk’ (2021) was featured in ‘Ether’s Bloom’ at Gropius Bau, an exhibition that kicked off the museum’s first programme on Artificial Intelligence. She has also recently undertaken research at CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research, in Switzerland, engaging her practice with technologies that expand human sensors and connection to the cosmos and celestial beings. We spoke with Domínguez about artistic imagination as a portal to envisioning what the notion of utopia could mean today, and about new ways of being and existing together.

Patricia Dominguez, portrait // Photo by Emilia Martín

Lorna McDowell: What led you from the field of ethnobotanical research to becoming an artist?

Patricia Domínguez: It was the other way around. I was always an artist, always connected with animals and plants, to the Earth and waters. Back when I was studying art at Hunter College in New York, I also studied botanical illustration and scientific illustration. I studied at the New York botanical garden for two years and then worked at the Natural History Museum of New York drawing fossils. I wanted to understand the relationship between the scientific gaze and living species. At first I was fascinated, but I reached a point where I was drawing a plant and I thought, “this can’t be the only way of describing this multi-dimensional being.” I knew it was much more than these hyper-realistic botanical drawings. I experienced a clash of views and became more interested in the relationship—symbolic, emotional or spiritual—that people can establish with plants or animals. I began to realise that I wanted to explore this via art, having the freedom to use fiction and to reimagine those relationships. Our relationship with the cosmos is still so limited, there’s so much that we can expand.

Art is a tool where imagination and emotion are the fuel. It can’t be defined by science and is just another language. Western science is so tightly tied to facts that I couldn’t really move out of that worldview if I worked in that area. I actually opened a school of botanical illustration when I came back to Chile, which I ran for 8 years. It was beautiful because it ended up being a way of really connecting with the local plants, learning about the ecosystems and their current destruction. The school became an activist activity. We would sit for hours drawing plants, without our phones, which was a very calm and meditative way of learning. When you paint one leaf you’ll never forget it. The drawing process is a tool for absorbing the information. It was a “scientific meditation” rather than believing that this is the ideal way of depicting plants. I truly think they’re multidimensional beings and that we need to invent new ways to represent them, at least from our human perspective. We need a much more experimental and spiritual “botanical illustration.”

Patricia Dominguez: ‘Matrix Vegetal,’ in collaboration with Emilia Martín, 2022, commissioned by Screen City Biennial with the support of Cecilia Brunson Projects

LM: There’s been a lot of discourse in recent times around Indigenous knowledge and plants. What can plants and ancient botanical wisdom teach us about how to live in these times? And about viable alternatives for the world?

PD: I believe Indigenous knowledge is sacred, and that we have a lot to learn from Indigenous communities because they know how to be here, on this planet. They have built a way to interact with the cosmos that is kind, respectful, a way that is really “sustainable,” to put it in Western terms. In these times of brutal ecological crisis, it makes total sense to me to want to learn from their ways. To rethink our models of extraction. My teachers and friends that are Indigenous or Mestizo have a spiritual and respectful approach to the planet, the mountains, the Earth, and they honour them instead of extracting from them or using them for money or power. They know how to never overuse them, and ask for permission before harvesting them, for example, they have alliances with the plants, collaborating with them and their healing medicinal qualities.

I feel this is the main approach we need to take in order to deal with this crisis. Where I live, Chile, is a lab for neoliberalism. Everything’s been extracted; the water is privatised, the forests are cut down, mining pollutes the few remaining waters. These days the central region is burning with fires that have caused great losses, especially of the few species that are still standing after the mega-drought, which was mainly caused by agriculture and forestries. It’s clear that this path is the path to destruction. Indigenous people also have an honoring approach to planetary memory. They know how to communicate with the elemental spirits in a dialogue that has never been broken. They are in a profound conversation with everything that is living, using a nonverbal language that cannot be explained rationally. Their science is spiritual.

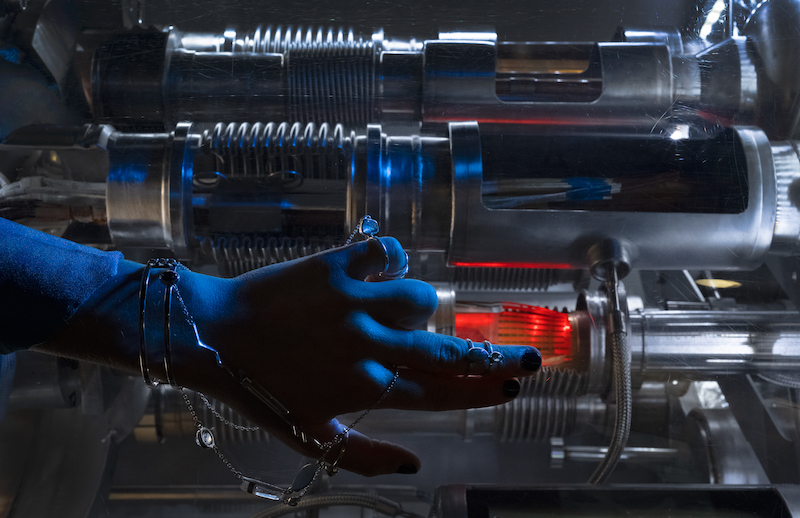

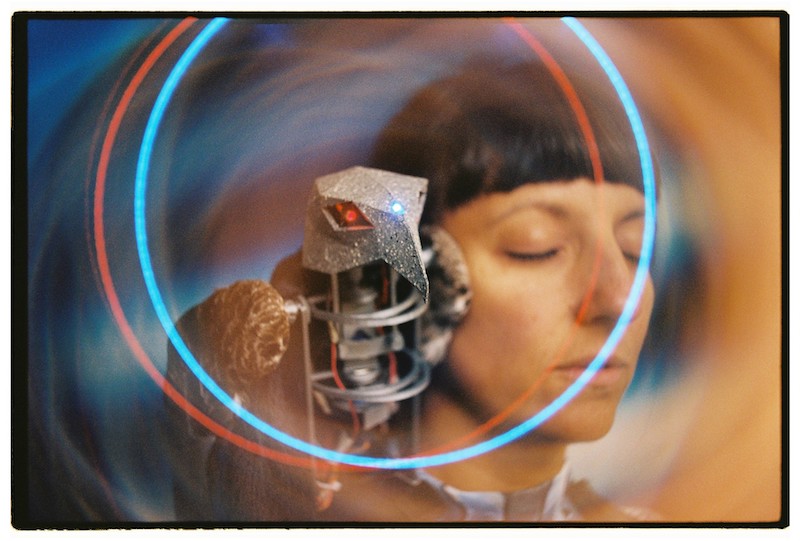

Patricia Dominguez: ‘Three Moons Below,’ 2024, with the support of Fundación Botín, Arts at CERN, ESO Observatories, Pro Helvetia, Corporación Chilena de Video and Ministerio de las Culturas, las Artes y el Patrimonio de Chile

LM: Can you explain a bit about your research at CERN in Switzerland and how this has fed into your work?

PD: I came to CERN on the Simetría Residency in 2021, a collaboration between CERN and Chile. It’s a beautiful residency because they offer you access to CERN experiments such as the ProtoDune (Neutrino Detector), n_Tof (Neutron time of flight) or CMS (Compact Muon Solenoid), among many others. Also the ESO Observatories in Chile; ALMA (Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array) the biggest radio telescope in the world, as well as the LSO (La Silla Observatory), which is located beneath the clearest skies in the world in the Atacama Desert. Visiting these places felt like a pilgrimage to the higher-end technologies of Western science. These technologies are expanding our connection to the cosmos, to celestial beings and to the invisible.

Coming to CERN really changed my mindset, as I was able to combine my own knowledge and learnings from spiritual techniques with the work of the scientists here. Witnessing their sense of wonder about the unknown is mindblowing. I got a sense of the microcosmos that even changed the way I dream. It opened up a strange immensity of reality. I learned that our particles can be entangled with particles in the Andromeda Galaxy, for instance. It made me ask: “Where is my limit?” It’s been very interesting for me to look at the LHC (Large Hadron Collider)—the world’s largest and highest-energy particle collider—as a mythological machine. Also, to think in terms of this spiritual connection that we were talking about before, whereby Indigenous communities can communicate with plant species or read people beyond time and space—they’re accessing a field, a dimension of consciousness, that we still don’t understand or know how to name.

I’m working on a fiction video called ‘Three Moons Below,’ which is a speculative, ancestral and futuristic video that explores mysticism and ritual while navigating fundamental science and cutting-edge technologies. In the video, a woman is guided by a robot bird on a pilgrimage to embrace different machines and technologies to acquire their capabilities. She longs for the vision and understanding of the radio telescopes of the ALMA astronomical observatory, the pre-Columbian petroglyphs of northern Chile, the neutrino detector and CERN’s LHC. They are artifacts of connection to the cosmos, to the Earth and to the irreducible reality. There are two doors, one to Western science, and the other is a shamanic portal to the universe. The protagonist moves through these two portals to activate new understandings. It’s a fictional way of depicting what has happened to me. The video production is supported with a grant from the Fundación Botín in Santander, Spain, and the finished work will be shown there in November 2024.

Patricia Domínguez: ‘Three Moons Below,’ 2024, with the support of Fundación Botín, Arts at CERN, ESO Observatories, Pro Helvetia, Corporación Chilena de Video and Ministerio de las Culturas, las Artes y el Patrimonio de Chile

LM: Why is it important to you that your work is both therapeutic and optimistic, as well as giving a strong political statement?

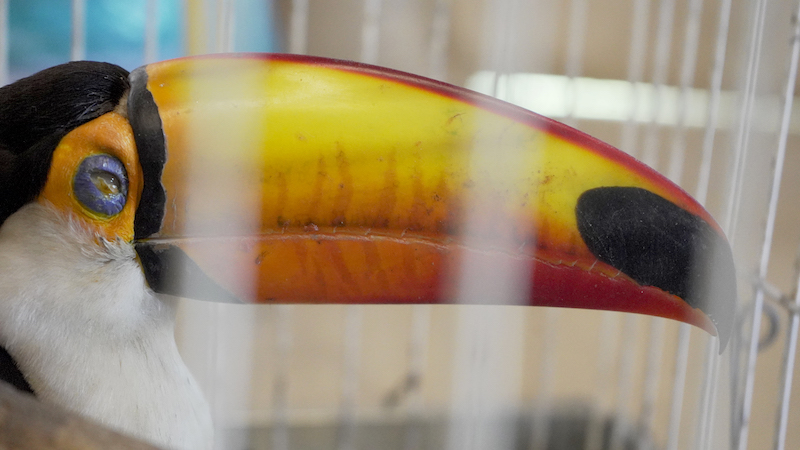

PD: What I do through my work is a ritual. I see it as late-capitalism hacking—a stomach that digests elements from the system and rearranges them into a sci-fi aesthetic, but where, actually, everything comes from the present. I re-appropriate objects from the internet in a way that honors planetary memory. The digital turns what is alive into pixels, whereas I materialise what’s digital, in order to connect it with memory, as pixels of information coming into us from the sky. By chance I was in the Bolivian Chiquitanía doing a residency during the forest fires and I helped out at an animal rescue sanctuary, where an injured, half-blinded toucan kept appearing. I made a video of it as a container or depository of memory. The toucan appears in ‘Madre Drone’ (2019-20), where I give him the mythological quality of being an animal with the ability to acquire a new kind of vision. The toucan appears crying, which was inspired by the tears of the students blinded with teargas by the police at protests during the social uprising around that time.

I see my works as emotional-organic technologies, where emotion is the fuel. It links the cosmos and more-than-human beings with the human viewer. The stories, narrated visually, extend a cord that moves through the eyes of the viewer, carrying the emotional experience of the work into their heart. The work is also bidirectional, linking the human to the animal or plant represented. This kind of emotional weaving is totally left out by the capitalist, corporate system we are in. The best thing that ever happens to me is getting messages from people who have seen my work, telling me that the toucan showed up under their dining table during a dream. The work has broken through their emotional and psychic barriers, placing this animal in their consciousness. I think of it as like an environmental service or offering, in a way.

Patricia Dominguez: ‘Madre Drone,’ 2019, commissioned by Centro Centro and produced in Residencia Kiosko, Bolivia

LM: In these times of despair about the tragedies happening in our world, what can the concept of “utopia” possibly mean for us? And what tangible role can artistic communities have in imagining and materialising something better?

PD: I think it’s a very difficult and complex question, and I think about it all the time. These days, for me the strongest potential utopia would come from combining the Buddhist tradition with permaculture philosophy. The idea that we are all interconnected and that if one person suffers, we all suffer, has stayed in my mind. We really need to activate a view not only of kindness for humans, but for all living beings, and to think about ourselves as a collective. Cosmos means community, too. Ideally we would think as one body distended in the planet, leaving nobody behind, right? Everyone, humans and those more-than-human, needs to be taken in consideration. We need to learn how to share. From there, we can start expanding the capabilities that we haven’t even started to activate. Invisible and organic technologies. But first we need to learn how to live together.

As for artistic communities, there are many and I can’t speak for everyone. But I resonate most with the experimental ones that embody art as a language to activate new understandings, technologies, invent new relationships, new world views, and who are critical about this digital age. Of course we all use technological tools—computers, phones—but I like the approach of emotionally connecting with what is living, beyond this fascination with machines and human made technologies.

I think all kinds of activism can be valid, whether going into the streets to protest or using social media. But personally, I was trapped in a violent cycle when it came to being an activist, and I thought, “okay, I need to learn new words, new ways of being, not only with humans but with all species in a way that is in solidarity and sustainable.” Now, my biggest form of activism is reimagining our planetary relationships, and how they might propose new ways of being and existing together.