by Adela Lovric, studio photos by Curtis Hughes // Mar. 5, 2024

Basma al-Sharif’s Berlin home exudes immediate warmth. Beyond the aesthetic of curated nostalgia—some of it personal while other items appear to be inherited from the city’s past—the space reveals a convergence of daily habits of living, working and playing. It seems all too fitting to discuss her artistic practice in her residence furnished with vintage finds, which closely resembles domestic setups of some of her artworks. In her installation ‘Trompe l’Oeil’ (2016), for example, she presents a mise-en-scène of her former living room in California, with a video loop at the center of it showing documentation of her daily rituals.

There is little separation between al-Sharif’s work and everything else that fills her everyday at home. Holding onto the idea that serious artists have to have a “proper” studio, over the years she would every so often rent one, especially when she needed to experiment with bigger installation works. “But I’ve always been aware that I hate it,” she admits. “I hate the process of getting ready and going to another space to essentially be alone there, and cold, in uncomfortable clothes and lacking food. I’m a smoker. If it’s not convenient to smoke, then I’m annoyed.” At her cozy apartment in Moabit, which she shares with her partner and son, the time for her creative flow is framed by her five-year-old’s kindergarten schedule.

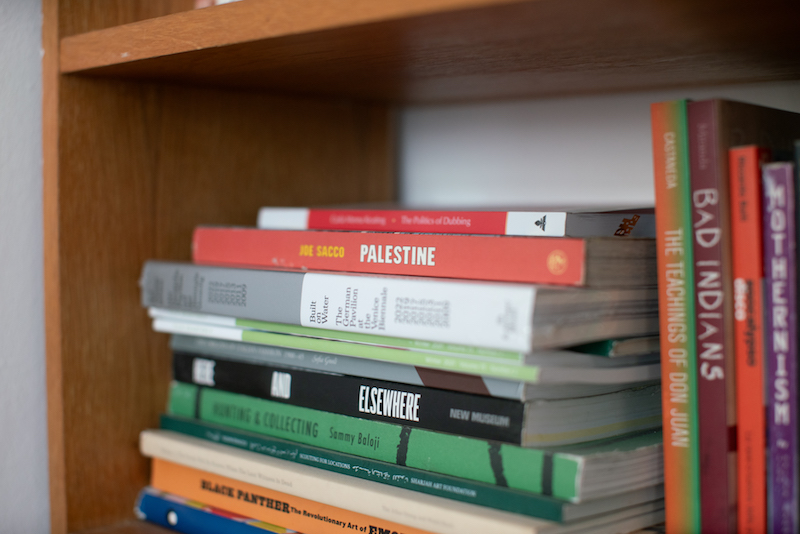

Domesticity is, in fact, one of the core themes of al-Sharif’s oeuvre. “I’m interested in the very small, the banal, the mundane, and because it’s not mundane for me, it’s something that’s very charged. I think it is charged regardless—how we inhabit a space, what is home, what is furniture and style,” she explains. It feels apropos to learn of her preferences for interlacing studio time with household chores, which she finds useful as it allows for a pause to resolve idea blocks that come up during a focused stretch of artistic work, whether it’s editing, doing research or developing something material-based.

While her Berlin base feels like the center of her universe, the larger idea of home remains somewhat elusive for the artist, born in Palestine and haunted by the diasporic condition from an early age. “I was born into a situation where we didn’t have a state, we didn’t have papers and my parents were trying to sort out where to live, and that’s basically how the rest of my life would go,” she explains. Having lived nomadically between Europe, the US and the Middle East since childhood, through her art, she grapples with the complexities of displacement. “I understand that what I have is just my perspective. When you’re born Palestinian and live outside of Palestine, you are made to feel that you don’t belong.” Moving from place to place inevitably shifts her perspective and even identity, which then also affects the ideas on which she works in a particular place. Traversing interiority and tapping into architecture, urban design and the organization of societies and cultures, al-Sharif finds commonalities across geographies, often returning to Palestine through her art.

‘Home Movies Gaza’ (2013), one of al-Sharif’s better-known video pieces, contrasts the idea of the boring repetitiveness of everyday life that unfolds again and again in the relative stillness of private spaces, with the depraved conditions of a territory stripped of basic human rights and under constant siege—“a microcosm for the failure of civilization.” Her feature-length film ‘Ouroboros’ (2017), filmed partly in Matera, a city in Italy where anti-fascists were exiled by Mussolini, draws parallels from Carlo Levi’s memoir between the experiences of its people and the people of Gaza under Israeli occupation—of “living in a place outside of time.” Coincidentally, Matera is also a place where Pier Paolo Pasolini shot his 1964 film ‘The Gospel According to Saint Mathew’ as a stand-in for Palestine, which he found to be both too modern and destroyed by occupation. In many of her other works, al-Sharif references her place of origin indirectly, situating herself in different locations and observing them through the Palestinian perspective to expose systemic violence and globally interconnected struggles.

Going against the mainstream proliferation of “iconically horrific” images of death and destruction, al-Sharif chooses subtler avenues of addressing difficult topics. Playing with the tricky relationships between images and language, representation and truth, she urges the viewer to question their learned understanding of the workings of the world. In her 2009 video ‘We Began by Measuring Distance,’ detachment from tragic facts about Gaza and the West’s orientalist view of a people takes an absurdist, poetic and even satirical turn to prove their futility in the face of willful ignorance and erasure. The artist faces the viewers with a combination of abstracted visuals, sounds and narration that highlight the distorted ways in which history is communicated.

al-Sharif’s upbringing was marked by political resistance of her family members who were activists, academics, humanitarian aid workers and politicians, among others. “But what touched me a lot more was growing up seeing poets, writers, musicians, filmmakers and painters, and feeling like that was also a testament to our existence—that we could do things beyond just thinking about our survival,” she adds. In making her mark as an artist, she decided she wasn’t going to try and prove the already well-documented violence, which prompted her “to think about how to represent it without showing it and how to take what’s happening in Palestine, more specifically Gaza, out of isolation and put it in dialogue with other places.”

Dialogue is just as important in the way in which al-Sharif approaches her artmaking. For her upcoming monograph with Galerie Imane Farès in Paris that represents her work, she decided on a structure that revolves around a nomadic development of her practice, but just as importantly, the people that she brings into each project and the connections that she has with them or starts to develop when meeting for the first time. As a process-based artist, she allows herself to leave things open to interpersonal interactions and influences. “Sometimes it could be one other person, and sometimes it’s 25 people, but I rely on it so much,” she admits. Collaboration as the lifeline of all of her projects is one of the main reasons she continues to pursue art with genuine pleasure and fully invested energy. “It feels like every project has a community that is created through the people I work with,” she adds. “And that’s a super beautiful process. It informs the work and shifts it.”

Artist Info

Festival Info

Berwick Film & Media Arts Festival

‘Filmmaker in Focus: Basma al-Sharif’

Mar. 7-10, 2024

Festival Pass: £55 (reduced £30)

bfmaf.org

Berwick-upon-Tweed, UK, Various Venues