by Alison Hugill // Mar. 15, 2024

For this year’s Venice Biennale, the Bulgarian Pavilion—located off-site at the Centro Culturale Don Orione Artigianelli—will feature the work of three collaborating artists, Krasimira Butseva, Lilia Topouzova and Julian Chehirian. In their multi-media installation, ‘The Neighbours,’ the trio explores the silenced memories of survivors of state violence from 1945 to 1989, colloquially known as

“domestic foreigners”—the name for those who deviated from the communist regime’s narrow ideals. These individuals were systematically persecuted as political dissidents and were often imprisoned without trial.

The installation, curated by Vasil Vladimirov and based on the theoretical framework of Topouzova, employs found objects, video and sound to convey the stories of individuals subjected to persecution in forced labour camps and prisons. The project, which is rooted in extensive scholarly research and over 40 interviews conducted by the artists, focuses on the ways in which individuals remember and articulate their experiences in the aftermath of traumatic events, and hopes to enact a space of collective healing and remembrance. We spoke to the artists—collectively referred to here as The Neighbours—about their project for the 60th Venice Biennale and how it might finally push the Bulgarian state to reckon with its past.

Portrait of the artists // Photo by Vasil Vladimirov

Alison Hugill: Can you briefly tell us a bit about the historical background of your exhibition, ‘The Neighbours,’ for those who aren’t familiar with the context?

The Neighbours: Forced-labor camps, and internment in them, figured prominently in the foundations of communist Bulgaria. In a country of seven million people, spread across 111,000 km², there were close to 80 separate sites where people were interned, often without trial during different stages of the communist regime. Inmates lived in terrible conditions, had to fulfill unbearable labour quotas, and suffered from hunger and violent punishment. The camp system was established during the country’s period of Stalinization from late 1944 to 1947, years marked by several waves of political violence. The severity of the different repressive practices varied widely, as did their timing. The most repressive phase lasted from 1945 until 1962, with the camp population reaching its peak late in 1949, and the camp system witnessing its most elevated level of violence in the early 1960s. The camps officially closed down in 1962, but the camp system was not dismantled. While rampant political repression ceased as an integral element of state-building, the Bulgarian camp network continued operating.

Unusually, during the later stages of Bulgarian communist rule, administrative repression continued, albeit at a diminished scale with fewer sites and victims, as well as with reduced visibility in society. Internment without trial and sentence took place in communist Bulgaria in the 1960s, 1970s and with renewed vigor from 1984 to 1987 during the communist state’s last forced-assimilation campaign against the country’s Muslim, Roma and Turkish minorities. The majority of people who were interned in the camps were never formally sentenced, nor did they know the reason for their imprisonment, or the duration of their imprisonment.

After 1989, there were several attempts at transitional justice, however they remained incomplete and unresolved. One of the key archival collections at the Ministry of the Interior was deliberately purged. In the absence of meaningful and concerted state and societal efforts to address the legacy of political violence, the memory of the camps has faded into oblivion. The multimedia installation ‘The Neighbours’ deals not so much with the historiography of the camp system, but rather with the aftermath of these events and their absence in collective memory. It presents ways of (not) remembering trauma, and how it is stored within our bodies—as individuals, and as a society.

Krasimira Butseva, Julian Chehirian & Lilia Topouzova: ‘The Neighbours,’ 2022, The living room, multimedia installation: found objects, video // Photo by Krasimira Butseva, Studio Benkovski 40, © Krasimira Butseva, Julian Chehirian & Lilia Topouzova

AH: In the framework of this year’s Biennale theme—’Foreigners Everywhere’—you tackle the stories of “domestic foreigners,” political dissidents persecuted from within. What can these voices tell us about our current moment?

TN: ‘The Neighbours’ is an installation that we have been developing for the past 10 years, which focuses on bringing to light the silenced and faded memories of survivors of political violence from Bulgaria’s state socialist period. The installation focuses on the voices and narratives of those who were systematically persecuted—political dissidents, peasants who wanted to hold on to their land, artists, queer people, Turkish, Roma, and Muslim minorities, youth who listened to jazz and ordinary people who deviated from the regime’s narrow ideals.

We see how authoritarianism continues to operate in the world today, and how individuals are persecuted for their beliefs, sexual orientation, or for opposing injustices. ‘The Neighbours’ is grounded within a practice of collective healing, remembrance and care. We believe that we can not only preserve the memories of these individuals, but also to propose a framework for acknowledging and coming to terms with traumatic pasts.

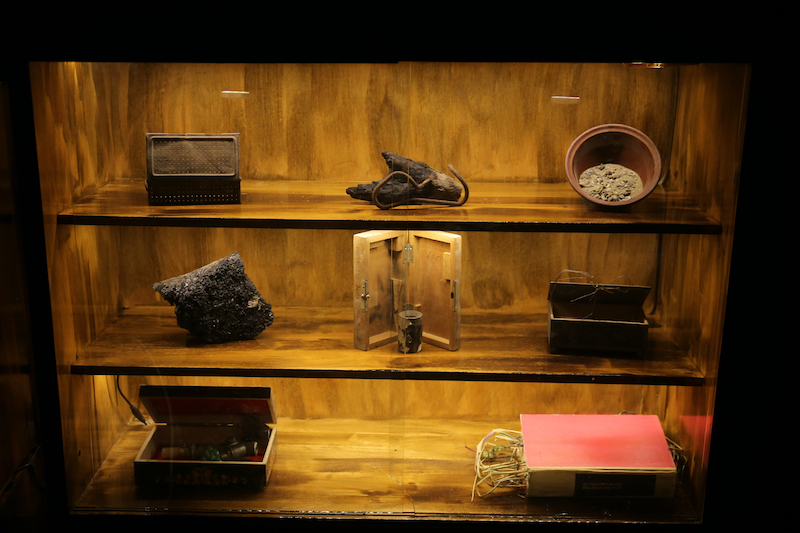

Krasimira Butseva, Julian Chehirian & Lilia Topouzova: ‘The Neighbours,’ 2022, the bedroom: cabinet with found objects from the former forced labour camp sites // Photo by Krasimira Butseva, Studio Benkovski 40, © Krasimira Butseva, Julian Chehirian & Lilia Topouzova

AH: The installations in the show are like replicas or time capsules, mirroring the homes of survivors. How did you source the objects in the installations? Can you talk about the significance of some of the items on display?

TN: The installations re-imagine the spaces where our interviews with survivors took place. The provenance of objects within them is as fragmented and varied as the memory of state violence in Bulgaria: recollection emerges in the least expected moments and places. Many of the items on display come from neighbours of ours and others, from flea markets, from second hand stores, and so often, from dumpsters and curb-sides around the city of Sofia.

Amongst them are artifacts that we’ve collected from scantly marked sites of political violence across Bulgaria: stones from a quarry labor site, reeds from the river bank of an island prison and labor camp, and a rusted tin of minced meat found in the ruins of the so-called “hooligans” barracks in the Belene camp. These items commingle with domestic materiality in the installations—passing on first glance as decor or souvenirs, and revealing themselves, upon closer attention, as freighted reminders of political repression and imprisonment.

This approach to collecting evokes the social practice that situates our work beyond the boundaries of the studio: what enters the installation must first be found, asked for, given or received. Those who help us look for, gather and otherwise source materials join us in the ongoing action of care towards the latent and otherwise overlooked whispers of the past.

Krasimira Butseva, Julian Chehirian & Lilia Topouzova: ‘The Neighbours,’ 2022, The living room, multimedia installation: found objects, video // Photo by Krasimira Butseva, Studio Benkovski 40, © Krasimira Butseva, Julian Chehirian & Lilia Topouzova

AH: You pair these found objects with sound and video, adding multiple dimensions to the presence of these traumatic memories. Can you tell us about some of the projections and audio that visitors might encounter?

TN: The installation operates as a landscape of spatialized sound and moving images. Projected and televised videos include nocturnal footage—often in detail—from the former labor camp sites Lovech and Belene. The former is an abandoned quarry, the latter still the site of an active prison on the Danube river. The nocturnal footage presents scintillating illuminations of shrubs, branches and other flora—quiet witnesses to the afterlives of these former sites of political-violence.

The sound in the installation emits from multiple sources. An enveloping soundscape wanders through a succession of field recordings from the former camp sites—sounds that are interspersed with field recordings from everyday domestic spaces. Refrigerator hums, coffee makers and footsteps on parquet floors merge uneasily with the sound of wind channeling over the Danube, the crunch of sunburnt algae on the cracked July riverbed, and the distant howl of coyotes beyond the high rock walls of the quarry in Lovech. Ordinary objects and furniture are transformed into acoustic bodies bearing field recordings and composed sound. In this way, both the domestic and camp topographies are alternatingly present and absent, and materials sourced from each become surrogates for latent memories of political violence.

Krasimira Butseva, Julian Chehirian & Lilia Topouzova: ‘The Neighbours,’ 2023, the kitchen, multi-media installation: found objects, video projection // Photo by Lubov Cheresh, Structura Gallery, © Krasimira Butseva, Julian Chehirian & Lilia Topouzova

AH: Why, for you, is remembrance an act of resistance? What pushed you to consider this kind of collective healing within the Bulgarian context today, nearly 35 years after the dissolution of the socialist republic?

TN: Remembrance is an act of resistance in a state that nourishes forgetting. We have been working, or rather resisting together and as individuals for the past two decades. Our efforts have taken the shape of artistic works, academic writings, panel discussions, participation in memorial days and, perhaps most significantly, in listening to the silent/ced voices of survivors. As our state has not committed to a narrative and position concerning its past, it appears that by way of the selection of this work for the Venice Biennale, one can be formed at long last.

Exhibition Info

La Biennale di Venezia

Bulgarian Pavilion: ‘The Neighbours’

Exhibition: Apr. 20–Nov. 24, 2022

bulgarianpavilionvenice.art

Sala Tiziano, Centro Culturale Don Orione Artigianelli

Rio Terrà Foscarini, 909/A, 30123 Venezia VE, Italy, click here for map