by William Kherbek // July 9, 2024

This article is part of our feature topic Desire.

Sofía Salazar Rosales’ recent exhibition at ChertLüdde, ‘The desire to dance with someone who is not there,’ explored the ways in which presence and absence fuel desire. Accompanying the exhibition was a text written by Dayneris Brito, in which the writer says the following of Rosales’ work: “sculptures are her dancing bodies, liquid bodies, penetrable bodies, bodies that hold space waiting for a partner to dance with. In short, the body knows more about the world than consciousness.” These kinds of somatic forms of knowledge and experience are at the heart of a practice deeply concerned with sculpture, architecture and the nature of embodiment itself. Rosales’ works are defined by material dialogues that often speak of loss, longing and hope. Such feelings are the substrate of desire, but desire, while personal, is never only personal.

Rosales’ origins in Ecuador and Cuba offer her a unique perspective on the geopolitical forces of extraction that have both shaped and been shaped by the dynamics of consumer desire. Her sculptural piece ‘Full of sweetness (y el mapeo del destierro)’ is a curtain made of fiberglass, epoxy resin covered with paraffin and medical adhesive tape, the title of which references the advertising slogan of the brand La Favorita—one of the main banana exporters in Ecuador. The drawing that appears on the banana boxes themselves can also be read on the curtain. In the following conversation, we discuss the personal, the political and the cultural manifestations of the many faces of desire in her work.

Sofía Salazar Rosales: ‘Zafra,’ 2021, raw cane sugar, fiberglass, wood glue, gelcoat, and resin, variable dimensions // Courtesy of ChertLüdde, Berlin and Sofía Salazar Rosales, Paris

William Kherbek: The exhibition at ChertLüdde acknowledges in its title the way that desire can be fed as much by absence as presence—as the cliche “absence makes the heart grow fonder” suggests. Could you elaborate on the ways in which you explore how absence engenders desire in the show?

Sofía Salazar Rosales: I was living in Ecuador for all my life until I was 18, then I moved to France. I started making my first sculptures when I was in second year at school. I was writing a lot of letters home, talking about this absence, and that led me to build shapes I knew, working from nostalgia and the desire for the presence of objects. Materials are not available in the same way, though. For example, one of the first pieces I made where I was aware of this was called ‘Meeting Spaces.’ This piece was a mat of woven cardboard and it’s a representation of an ester, a mat that exists in Ecuador, but is always made from the Totora plant, which is very local.

When I arrived in Lyon, of course they didn’t have this plant, so I needed to find another material. I started using cardboard, which was very present in the city. I started making lots of objects I used to know, but with different materialities. There is also a desire to make people see pieces and not really be sure how they’re made. And also, having all these industrial-seeming objects, but they are handcrafted from scratch. Working from the word “reconciliation,” I try to create this meeting of other contexts that I know, gestures that I know, with materials that are new, that are present in the context that I’m currently living in. This desire came from an absence. I think the word “desire” in my work will always be from absence, from wanting to have something that is not possible to have.

Sofía Salazar Rosales: ‘Meeting space(s),’ 2023, installation view of ‘Pays rêvé, pays revers,’ Petite Galerie – Cité internationale des arts, Paris // Photo by Kevin Andrés Cristi, courtesy of ChertLüdde, Berlin and Sofía Salazar Rosales, Paris

WK: Your recent show at Alice Amati Gallery in London references a song title. Popular songs of course use desire as fundamental subject matter and influence our general construction of the concept. I wonder if you could talk about how desire filtered through musical forms has affected your approach to work?

SSR: It’s very new in my work to use songs, but they’ve always been a part of my life. For example, with my grandmother, I was always listening to boleros—very romantic music but also very sad and sensual; so there is a part of desire there, and in salsa and reggaeton, too. There is always this presence in the type of music I listen to, as in my sculptures. They are talking about violent and sad contexts in a way, in their materiality, and, in the way that I build them, I try to make them attractive. Not really beautiful, but maybe sexy? They’re shiny, attractive because they’re different or ambiguous. There is also a desire to touch. I create leaks in the pieces, using a materiality that has a very human weight and that’s also important because [in an exhibition] you’re dancing. You’re walking around without touching, you’re invited, but you’re not physically allowed to touch because of the etiquette of the gallery and museum spaces. You’ve invited someone onto the dance floor, but they’re not allowed to touch, and that in itself already brings about desire.

Sofía Salazar Rosales: ‘The desire to dance with someone who is not here,’ installation view at ChertLüdde, 2024 // Photo by Marjorie Brunet Plaza, courtesy of ChertLüdde, Berlin and Sofía Salazar Rosales, Paris

WK: Inevitably, thinking of desire in contemporary society, it’s informed heavily by capitalist imperatives. How does your work think about these ways in which desire and consumption relate?

SSR: Desire is very political. Who you desire, and how society teaches you how to desire. It’s even present in everyday things, like bananas. It’s kind of funny to me that in Ecuador, which was the first country to export bananas in the world, the bananas I buy are not “beautiful” like the bananas I buy here—so it’s also how this journey, this trade flow, makes them beautiful and desirable, instead of being white or black, here they’re green and big and perfect with no marks. And all the boxes show colours and landscapes that are not really like that. It’s kind of crazy the way this product is sexualised. The most known company is Bonita, which means “beautiful,” or Chiquita, which is “small one,” and the words are always in the feminine in Spanish. There are all these desires in bananas, the phallic form but it’s also visually contextualised in the feminine.

Sofía Salazar Rosales: ‘Full of sweetness (y el mappeo del destierro) (detail),’ 2024, installation view of ‘The desire to dance with someone who is not here,’ installation view at ChertLüdde, 2024, metal, paraffin, surgical tape, epoxy, fiberglass, 366 x 170 x 12 cm // Photo by Marjorie Brunet Plaza, courtesy of ChertLüdde, Berlin and Sofía Salazar Rosales, Paris

WK: On the subject of the banana in art history, one might think immediately of Warhol’s Velvet Underground album cover, with the peelable banana—itself implying an act of desire—or of Maurizio Cattelan’s banana taped to a wall. In addition to phallic connotations, bananas have this inscribed dimension of revealing and concealing. The hidden is often desirable, but also easily made into the other, and so the colonial history of the objects begin to play a role in understandings of it, especially in relation to South American countries more or less economically subordinated to agri-business to produce these—for lack of a better term—”fruits of desire.”

SSR: I’m always talking about the bananas as if they were people. These pieces are about this context, too, how the US can use a product to control a country in Latin America. When I was in school, we were learning about the First World, the Second World, etc., but at the same time it was linked to agro-exportation. We were having history lessons through products, which is crazy, no? And it’s crazy because things haven’t really changed. If you see it from the perspective of Latin America, they have been talking about bananas forever. It’s crazy that we’re still talking about it. We’re still exporting raw materials, and we depend on mainly three or four products that come from the soil, in order for people to make a living.

I don’t know if I really openly gesture towards these ideas in the work, though. Most of my work came just because it was what I knew. It’s more like an observation, I’m not trying to moralise to the world. I’m showing a position, in all my pieces, but somehow the exhibitions become about bananas, without my noticing really.

WK: Having moved to Europe, are you noticing major ways in which desire functions differently between say Ecuador or Paris or Amsterdam?

SSR: In Paris, I have a lot of desires I would prefer not to have. Especially material. It’s a city where you want to have a lot of things. In Amsterdam, it’s not a city where you need a lot of things, everything is practical there and it’s also kind of baroque and complicated, whereas Paris is a very ambitious city.

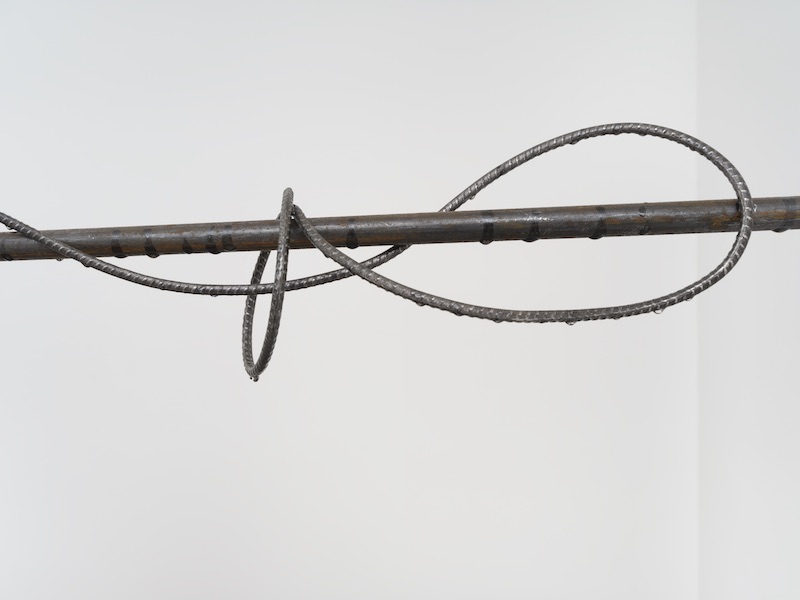

Sofía Salazar Rosales: ‘While the wounds are open (detail),’ 2024, Installation view of ‘The desire to dance with someone who is not here,’ ChertLüdde, 2024, glass beads, gauze, padding, paraffin, plaster, iron filings, cardboard, chicken wire, metal, fiberglass, polyester resin and epoxy, 207 x 90 x 282 cm // Photo by Marjorie Brunet Plaza, courtesy of ChertLüdde, Berlin and Sofía Salazar Rosales, Paris

WK: Are there things these European imperatives of desire gloss over or miss out on in your work?

SSR: I think a lot is missing. I often need to contextualise a lot more here, but if I’m showing in Latin America my way of talking would be different. I was living in Quito, the capital of Ecuador, which is a place that’s more under construction. Seeing how things grow is very different. In Paris, on the other hand, everything is already set in a way, and they’re just making the city bigger. But they don’t change the historic city.

I have a piece about Paris called ‘While the wounds are open.’ It’s really about how this city is full of holes and it’s being repaired so much that you have sheet metal everywhere. It’s part of the city’s landscape, but we really don’t think about it, even though it allows us to circulate. The city is not allowed to stop so it can heal. All these holes are being opened and repaired, but there’s no time to pause, because the repairs happen while the city is moving, and it’s not healing well.