by Philipp Hindahl // July 22, 2024

There is a chance that upon entering ‘A Time in Pieces’ at Between Bridges in Berlin, the first thing visitors hear is the abrasive sound of air raid sirens that accompanies Lesia Vasylchenko’s work—‘Chronosphere’—which is part of a longer single-channel video. The Oslo-based artist broke the work up into three parts that play across several screens, and they are embedded in an installation, made from the stainless steel parts of a turnstile. The video, with its hectic images of people rushing down stairs to a bomb shelter, speaks about chronopolitics—the weaponization of time for political ends—and this body of work explores, in particular, how this politics overlaps with technology. The images in the video tie in neatly with the way the curators think about the politics of time, a present condensed by displacement and war, a future forcefully cut off. As the videos play simultaneously, Vasylchenko problematizes the idea of a unified now.

Lesia Vasylchenko: ‘Chronosphere,’ 2024, video installation, sizes variable, 8:30 min // Courtesy of Between Bridges, 2024

The Kyiv Biennial started in a particular moment when it was first held in 2015. War had already come to Ukraine: the 2014 war in Donbas was a prelude to the 2022 invasion, and the following year, the biennial was disrupted by an ongoing war of aggression. The curators—among them Serge Klymko, co-founder of the biennial and co-curator of the show in Berlin—decided to turn it into an itinerant event, across Kyiv, Ivano-Frankivsk, Uzhhorod, Warsaw, Vienna, Lublin, Antwerp and finally, Berlin. Conceived as a fractured project in venues across the city, it remained here as the Kyiv Perennial.

The first part, which opened at Between Bridges just before the anniversary of the full-scale invasion this year as part of the Kyiv Perennial, conveyed a sense of urgency, as it focused on the present and the experiences of the Ukrainian community. It bore witness and spoke to the immediacy of making art in times of war. The second one, ‘A Time in Pieces,’ curated by Klymko and Viktor Neumann, operates at a different pace.

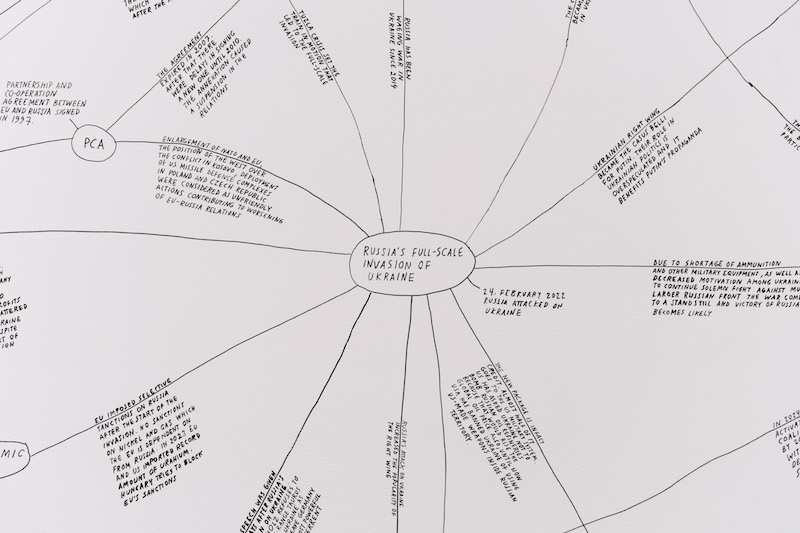

Minna Henriksson: ‘Zeitenwende,’ 2024, wall drawing, sizes variable // Courtesy of Between Bridges, 2024

Take Minna Henriksson’s hand-drawn, wall-sized diagram titled ‘Zeitenwende.’ Arrows link short passages of text, some terms are circled and it recalls visualisations of interlocking crises, known as polycrisis. The Helsinki-based artist collaborated with Ukrainian historian Georgiy Kasianov, and the piece traces the prehistory of the full-scale invasion, since 1945. She links events in a loose manner, avoiding linearity. Euromaidan (a wave of demonstrations across Ukraine) is followed by the annexation of Crimea, which is related to the aggressively imperialist ideology of the so-called Russian World, followed by the invasion, and at the very end, Henriksson sketches scenarios for how the war might end. History is multidirectional, contingent, often scrambled and synchronous, but above all, historiography, in this representation, is subjective. ‘Zeitenwende’ was the term German chancellor Olaf Scholz used when he proclaimed that we are entering a new era, but detached from politics, it might as well describe a new intensity and simultaneity of events.

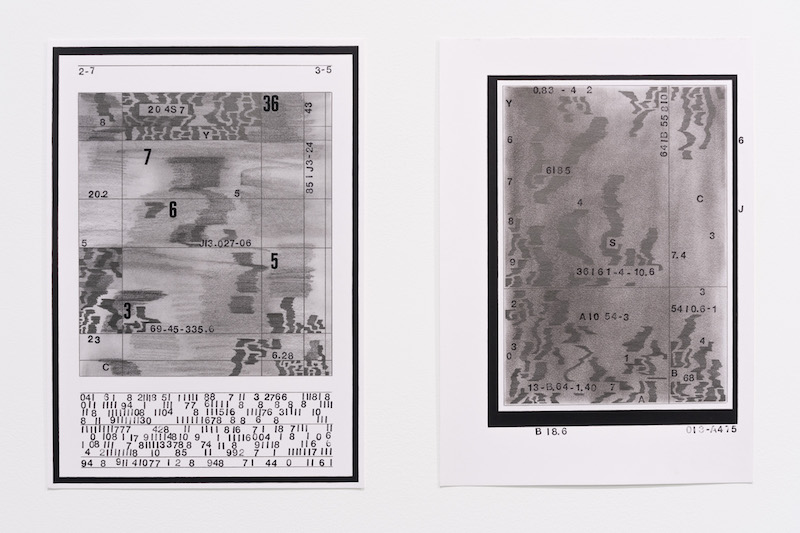

The CVs of many of the artists in this show testify to this. They, too, are non-linear and marked by displacement. Daria Chernyshova came to Berlin before 2022 and faced many bureaucratic obstacles. Her diary-like drawings on printouts of forms collapse meaning into a nervous, idiosyncratic code of hardly legible signs, as if to document the exhaustion of meaning.

Daria Chernyshova: from the cycle ‘Intuitive Practice,’ 2019–ongoing, various techniques on paper, 42 x 29.7 cm each // Courtesy of Between Bridges, 2024

In the small, cabinet-like room in the back of the gallery, a video by Dana Kavelina displays an excess of meaning. In ‘The Order of Neat Beds,’ choral works by the medieval mystic Hildegard von Bingen play in the background, as Kavelina reads the suicide note of a fictional artist over a collage of cartoons, footage from the heavily industrialised Donbas and Ukrainian television from the 90s. The video deals with mysticism and its metaphors: light comes to us with delay, like a message from the past, but it is also an image of impending death. The room is enclosed with translucent white curtains, reminiscent of a makeshift hospital bed. The film is projected from the back onto one of them, and to watch, viewers must squint into the light.

Dana Kavelina: ‘The Order of Neat Beds,’ 2020/2024, video installation, sizes variable, 13:30 min // Courtesy of Between Bridges, 2024

Every room in this show has its own atmosphere, and a piece by Vova Vorotniov dominates the darkened basement of the project space. Vorotniov has stacked porous grey bricks into a cube—a minimalist gesture and a reference to the piles of bricks often found in Ukrainian villages and suburbs. They figure as investments, to build annexes or garages, and more abstractly, as tangible hope for the future. However, this future never arrived, and in the war-ravaged regions of the country, often the only remainder of destroyed houses is a pile of bricks.

‘A Time in Pieces,’ installation view // Courtesy of Between Bridges, 2024

Sonically, the space is dominated by Roman Khimei and Yarema Malashchuk’s double projection of ‘Dedicated to the Youth of the World II’ and ‘Dedicated to the Youth of the World III.’ Khimei and Malashchuk have already contributed to the first instalment of the show. In their video ‘Explosions Near The Museum,’ for which they filmed the looted galleries of a history museum in Kherson, just after the city was liberated, the stolen artefacts haunt the rooms. ‘Dedicated to the Youth of the World’ widens the scope, and it consists of two parts, the first filmed at a techno party in 2019 and the second in 2023, juxtaposing formally similar frames. They create an image before and after: a moment in the late 2010s, when political hopes were placed on a future Ukraine aligned with the EU, and a country post-invasion. One can easily catch oneself looking for signs of the outside world in the footage of seemingly oblivious dancers. Who, from the 2019 video, may have been conscripted? Do the dancers look wearier in 2023, aware of their precarious and intensified present? One shot echoes the other, and little time separates them, and yet they seem so far apart in a history that is still relentlessly being made.

Exhibition Info

Between Bridges

Group Show: ‘A Time in Pieces’

Exhibition: May 24–July 27, 2024

betweenbridges.net

Adalbertstraße 43, 10179 Berlin, click here for map