by Marta Jecu // Aug. 27, 2024

Reloading and re-launching the old and thorny debate on the shifting grounds of inclusion in contemporary art, ‘Foreigners Everywhere,’ curated by Adriano Pedrosa, explicitly sets the intention to display works by artists from the Global South, the art of indigenous people, the work of queer artists, of folk and collective artists, as well as historical artists who have never participated in the International Art Exhibition. Brought together under the ambiguous and politically-charged notion of the “foreigner,” the works affiliate themselves not only thematically, but also aesthetically with these under-represented groups, displaying techniques that have been marginalised from the field of contemporary art—applied arts, untutored and collective crafts–and that also document their social and political contexts. This year, the main exhibition features an increased amount of artists in relation to the previous editions, summing up 331 artists, of whom more than half have already passed away.

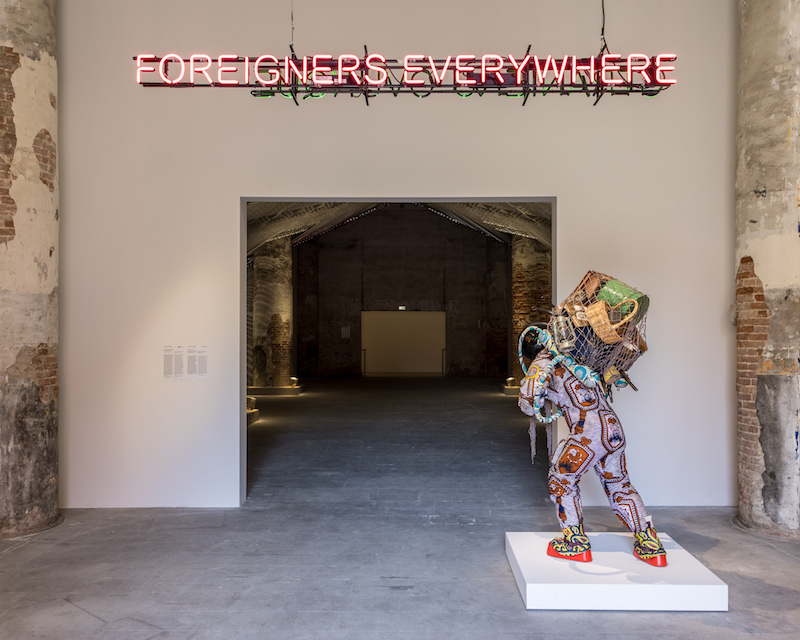

Claire Fontaine: ‘Stranieri Ovunque (Autoritratto), Foreigners Everywhere (Self-portrait),’ 2024, double sided, wall or window-mounted neon, framework, transformers, cables and fittings, dimensions and colours variable // Photo by Marco Zorzanello, courtesy of La Biennale di Venezia

Spectacularly adorning the Giardini’s facade with its fantastic colours, fauna and scenes of life, the mural by the collective MAHKU makes a both decisive and welcoming curatorial statement, introducing an incursion into the reality of indigenous cosmogonies. A non-chronological Native and First Nations perspective on history and the past rings through many of the works on display.

MAHKU (Movimento dos Artistas Huni Kuin): ‘Kapewe Pukeni [Bridgealligator],’ 2024, site-specific installation, 750m2 // Photo by Matteo de Mayda, courtesy of La Biennale di Venezia

The main exhibition in Giardini and Arsenale, showing a significant amount of historical drawings and paintings, has a museum-like feel, elegantly displayed without artifice, offering space to the works themselves and not to the mastery of “curating.” We are faced with an encyclopedic repertoire, minimally structured, which could at first appear to be grouped by formal criteria; at a second look, the display seems to be rather associative and intuitive.

The main exhibition includes contemporary works and three ‘Nucleo Storico’ sections, focused on modernisms of the Global South: “on a chronological arc (1915 to 1990),” Pedrosa notes, “that is much wider than the typical modernist time frame.” With this show, Pedrosa contests a centralised modernist current emanating from the Western world to the so-called peripheries, delivering the image of a cross-pollinated modernity, situated between a multitude of sources and temporalities.

Photo by Andrea Avezzù, courtesy of La Biennale di Venezia

In the Central Pavilion, one section of the ‘Nucleo Storico’ is devoted to the rather general and broad theme of portraits, while the second section displays abstraction. Global artistic personalities whose work promoted emancipation and critical thinking in the 20th century are given their due throughout these two sections: from the paintings of the Turkish opera singer and artist, Semiha Berksoy, the social realist paintings of urban scenes by the South African artist, Gerard Sekoto, or the abstract minimalist paintings of Japanese Brazilian artist, Tomie Ohtake. In the Arsenale, the ‘Nucleo Storico’ displays the Italian diaspora of the 20th century who settled in Africa, Asia, Latin America, Europe and the United States, reiterating the glass display panel system designed by Brazilian architect Lina Bo Bardi for São Paolo’s MASP, where Pedrosa is director.

Lina Bo Bardi: ‘Cavaletes de vidro,’ 1968/2024, concrete, glass, wood, neoprene and stainless steel, 240 × 75cm; 240 × 100cm; 240 × 150cm; 240 × 210cm // Photo by Marco Zorzanello, courtesy of La Biennale di Venezia

In the contemporary works collections of the main exhibition the theme of migration stands out, as well as its relation to multi-layered exclusion systems. Taking as a premise the inclusion and identification of specific (hitherto) marginalised groups runs the risk of reinforcing those categories. Bringing together queer artists, indigenous artists and artists from the Global South, folk artists and collectives under one moniker—whether the ‘marginal’ or the ‘foreigner’—simultaneously pins down their production to these categories and risks instrumentalising it within the context of mass art consumption. Pedrosa’s cross-cultural, cross-temporal display partly equalizes the works, however, instead of differentiating the artists or pigeon-holing them in their contextual cultural specificity. The act of including indigenous art in a contemporary art exhibition implies annulling its cultural function and displaying it under aesthetic or thematic equalising denominators. Since the opening, many have asked: to what degree can these attempts be decolonising?

Pablo Delano: ‘The Museum of the Old Colony,’ 2024, Installation, variable dimensions // Photo by Matteo de Mayda, courtesy of La Biennale di Venezia

Pablo Delano’s ‘The Museum of the Old Colony’ (2024) in the Central Pavilion provides a radical answer: his installation archive meticulously documents repressive acts of Spanish and US domination exercised over indigenous communities and communities of African descent in Puerto Rico. Here, the Biennale becomes a platform for communicating otherwise censored information.

Bordadoras de Isla Negra: ‘Untitled,’ 1972, embroidered canvas, 230 × 774cm, collection Centro Cultural Gabriela Mistral // Photo by Marco Zorzanello, courtesy of La Biennale di Venezia

The contemporary section in the Arsenale is dominated by artisanal, often collective work. The brightly coloured, embroidered wall hangings of the Bordadoras de Isla Negra—a group of Chilean women active between 1967–1980—document daily life scenes detailing social activities and personalities of the time. The work of another group of unidentified Chilean Women called the Arpilleristas show patchwork textiles with colourful scenes in popular neighbourhoods, that manifest the need for social harmony during Augusto Pinochet’s military dictatorship in Chile. The exhibition highlights Latin American production, but reveals significant research on artistic healing and reparatory practices on a global scale, connected to wars and social insecurity. The Palestinian-born artist Dana Awartani displays an installation of hanging silk textiles, dipped in the warm colours of herb- and spice-based natural dyes with medicinal properties, which the artist studied in India and in Saudi indigenous communities. Pacita Abad, born in the Philippines, developed ‘trapunto’—a technique of painting on previously embroidered fabric, on large scale canvases with graphic scenes in the global urban contexts she travelled through in the 1970s-90s.

Dana Awartani: ‘Come, let me heal your wounds. Let me mend your broken bones,’ 2024, darning on medicinally dyed silk, 520 × 1250 × 297cm // Photo by Marco Zorzanello, courtesy of La Biennale di Venezia

Unlike in the Giardini, where drawing and painting abound, in the Arsenale video also punctuates the parcours. The Disobedience Archive, brought together and curated by Marco Scotini, is an ongoing collection of activist films, developed by Scotini since 2005 and shown around the world, in various displays. The current design by Juliana Ziebell (who also designed the main exhibition), favours less the possibility of watching the individual films in their entirety, but rather foregrounds the connection and networking between these different types of activisms—gender, postcolonial and migration-bringing together related struggles.

Bouchra Khalili: ‘The Mapping Journey Project,’ 2008-2011, video installation, 8 single-channel videos, color, sound, variable dimensions // Photo by Marco Zorzanello, courtesy of La Biennale di Venezia

Bouchra Khalili’s ‘The Mapping Journey Project’ (2008–11) is another notable piece, which was a landmark in the context of migration debates and studies. Displayed on immersive screens, it shows maps on which migrants recount their peregrinations from the Middle East and North Africa towards Europe. Meanwhile, Ivan Argote’s video ‘Paseo’ (2022), also brings together questions of civil disobedience, migration, public space and theories around monuments. This work shows a decolonial fiction of the journey of the Columbus statue, taken down from Madrid’s Plaza de Colón and riding through the capital in exile.

Kiluanji Kia Henda: ‘The Geometric Ballad of Fear (Sardegna ),’ 2019, inkjet print on fine art paper 100 × 120cm each // Photo by Marco Zorzanello, courtesy of La Biennale di Venezia

Kiluanji Kia Henda’s photography series ‘The Geometric Ballad of Fear’ (2015), ‘The Geometric Ballad of Fear (Sardegna)’ (2019) and his installation ‘A Espiral do Medo’ (2022) show metal window grids taken from houses in Angola, which allude to fractured identities, situations of hiding and the feeling of foreignness and imprisonment in one’s own environment, reiterating the fundamental themes of this year’s Biennale.

Overall, Adriano Pedrosa’s ambitious main exhibition is evidence of a refreshing “slow” work, not only for the meticulous nature of many of the artisanal works presented, but also for the meditative temporality and sedimentation that the works display, from the Disobedience Archive’s sweeping scope, to the revival of works like Susane Wenger’s multi-disciplinary work in Nigeria in the 1960s and 70s, or the research-based work on queer micro-histories of Kang Seung Lee, displayed in the Giardini.

Exhibition Info

La Biennale di Venezia

Group Show: ‘Stranieri Ovunque – Foreigners Everywhere’

Exhibition: Apr. 20-Nov. 24, 2022

labiennale.org

Giardini della Biennale, 30122 Venezia VE, Italy, click here for map

Arsenale di Venezia, 30122 Venezia VE, Italy, click here for map

*This article was published in the framework of the research project CARIM. Contemporary Art: A pathway towards Inclusive Museology.